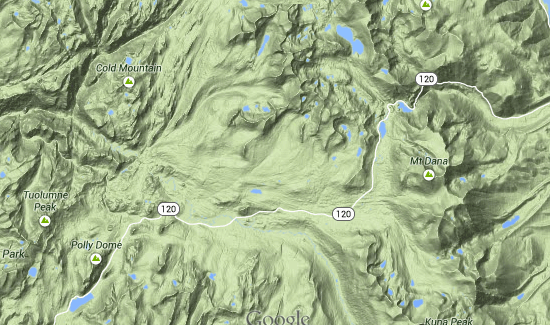

One of many iconic landscapes in Yosemite National Park is a wide-open grassy stretch mixed with high granite outcrops called Tuolumne Meadows. Millions of visitors have stopped there in wonder. Geologists love a good view as much as anyone, but sooner or later they ask themselves the strange but typical question, “How did this landscape happen?”

Tuolumne Meadows is a long-standing geological puzzle—a large relatively flat place in the midst of a rugged range.

Like most of the high Sierra valleys, the Meadows were covered by ice age glaciers until very recently (in geologic time), just 12,000 years ago or so. So in the Sierra, the geologists’ question usually boils down to “How did the glaciers make this landscape?” At Tuolumne Meadows, their question is “How the heck?”

Tuolumne Meadows is geologically weird because it mixes a wide flat area, typical of weak bedrock, with big humps of clean strong stone, like Lembert Dome, exposed like sculpture in a gallery. But the whole area is in one large body of identical granite, the Cathedral Peak Granodiorite. (Granodiorite has a slightly different blend of minerals from true granite; only geologists notice. Most of the Sierra’s beautiful white “granite” is granodiorite.) The clean crags that Yosemite rock climbers love are cheek by jowl with flat, well-eroded meadows, all in the same rock. How did the glaciers carve the same stuff into such a variety of landforms?

Geologist Richard Becker and three colleagues have unraveled the puzzle in a new paper for GSA Today (open access). They say the key is the cracks in the granite.