It was a truly history-making mission to the deep Earth that drilled a 2-mile borehole to the active trace of the San Andreas fault. Today the San Andreas Fault Observatory at Depth, or SAFOD, languishes just short of its goal, and scientists are scratching for funds to place instruments where they were meant to be.

SAFOD began ten years ago as the boldest part of the great EarthScope research program. Two other EarthScope projects have crossed the nation with a giant movable set of seismometers (USArray) and blanketed the western states with GPS receivers to monitor crustal movements (Plate Boundary Observatory). The SAFOD project gave us the means to witness earthquakes close up, while they happen.

A site was picked in the tiny town of Parkfield, California, where the San Andreas fault is well behaved (for a fault) and where earthquake scientists have had a presence for many years. A scientific drill rig was set up on a site provided by a generous cattle rancher, and work began in 2002 with an exploratory hole. Three years later, I saw the rig in action as it prepared the main borehole, which started straight down, then curved eastward to intersect the fault from the side. As expected, the fault zone itself was marked by about 200 meters of shattered and altered rock.

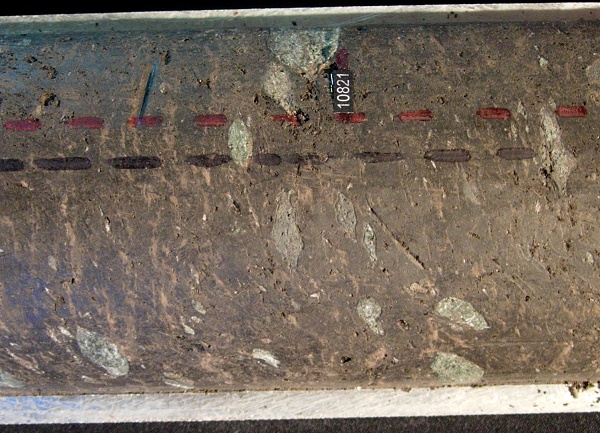

The next trick was to find the active plane in that wide fault zone. The borehole was lined with steel casing and then monitored for a couple of years. The fault was pinpointed in two places where it was gradually warping the casing. The next phase of the project targeted these places, drilling sidetracks from the main hole and collecting cores of undisturbed rock from them. These alcoves were where a set of six sensitive instruments—the downhole observatory—was installed in September 2008.

The cores, as precious as moon rocks, were displayed to the press on October 5, 2007. It was a privilege to see them with my own eyes. Today they are stored in a Texas facility, where samples are parceled out to qualified researchers.

Unfortunately, the downhole instruments failed after a few weeks in the harsh conditions. A new seismometer was lowered into the hole and continues to yield good data; SAFOD scientist Bill Ellsworth told me that a replacement is on the way. But beyond a shoestring of funding that various sources have been scraping together, the money is gone and we’re left with half the result that scientists hoped for.