Since 1972, California law has forbidden builders and homeowners from building on earthquake faults that cross their property. 40 years later, some of those strips of hazardous land have turned into amenities: unexpected greenbelts that have attracted high-value homes and people to match, according to a study in the upcoming issue of the journal Earth’s Future.

The 1972 law began as the Alquist-Priolo State Special Studies Zone Act, a name designed to reassure the skittish. It mandates that the state map all hazardous active faults, and all property owners within a certain distance of the fault must disclose the fact to would-be buyers.

Wouldn’t this scare people away from houses sitting next to an earthquake fault? The Bay Area’s largest set of such homes is on the Hayward fault, which runs the length of the East Bay from Point Pinole to Fremont. I’ve heard stories of fault-line residents who resent visitors gawking at their cracked sidewalks and warped driveways. I once owned a home in an Alquist-Priolo zone, and it was a nervous-making experience to inform prospects during the sales process. Yet the homes still sell. And now the law has a more straightforward name, the Alquist-Priolo Earthquake Fault Zone Act.

Existing homes on the fault are exempt from doing much about it, which takes some of the sting out of the predicament. So while you’ll see decrepit houses or vacant lots here and there along our active faults, studies have shown that the Alquist-Priolo law has little effect on home values. The law makes a real difference in greenfield developments, where new homes are built on previously empty land. In the new study, a team of researchers led by Nathan Toké started out thinking that the law might stigmatize these places, but they found instead that wealthy people appear to be attracted to the fault.

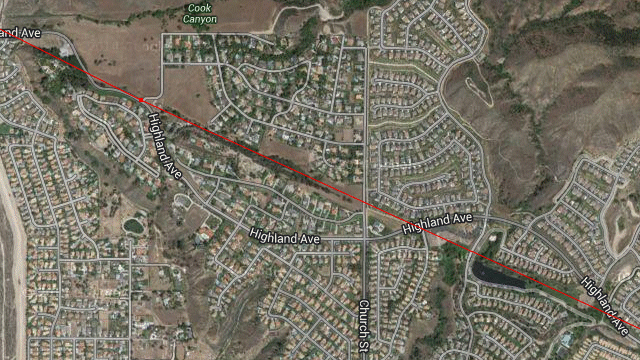

For a fun way to use Google Earth, plug in the government’s maps of earthquake faults as you hover over Southern California cities. You’ll soon see places where greenbelts and parks line up along an active fault. This image shows part of the suburban town of Highland, just east of San Bernardino, where the San Andreas fault runs.

This curious pattern is familiar to most of us who think a lot about earthquake policy. Toké’s team went a step further, using geographic databases to examine the effect more precisely. They had detailed census data to overlay on the official Alquist-Priolo maps—household wealth, residents’ ages, minority status, population density, age of the housing stock and so on. From this data they devised a measure of “social vulnerability” for each census tract. As expected, their analysis showed that highly vulnerable tracts are clustered near environmentally toxic locations. But when it came to the hazard of earthquake shaking, Alquist-Priolo zones are favored by what you might call the socially invulnerable—well-off people with good jobs.