What Actually Makes Water Roll Off a Duck's Back?

Video by Josh Cassidy

Article by Annie Roth

Summer is a great time to be a bird watcher in California. Ducks, geese, and many other species of aquatic birds come to California to breed, build nests and raise broods. If you go to your local pond right now, chances are good that you will see a mallard or Canada goose paddling along with a gaggle of its offspring in tow.

But watch for too long and you might find yourself wondering “how do these birds stay warm and dry in the water?”

It’s a question that Jack Dumbacher, curator of ornithology and mammalogy at the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco has been asked many times.

The secret to waterproof waterfowl, it turns out, lies in their feathers.

“Aquatic bird feathers are really different than those of other birds,” Dumbacher said.

All birds have feathers. Their size, shape, and structure vary widely, but all feathers fit into one of two categories: down or contour.

Contour feathers, which include flight and tail feathers, are the long, rigid feathers that give birds their shape and color. As the outermost layer, contour feathers serve as a bird’s first line of defense against the elements.

Down feathers, by contrast, are the soft, fluffy feathers that sit closest to the bird’s skin. These keep birds warm by trapping a layer of air next to their skin and are used to make comforters, pillows, jackets, and other products.

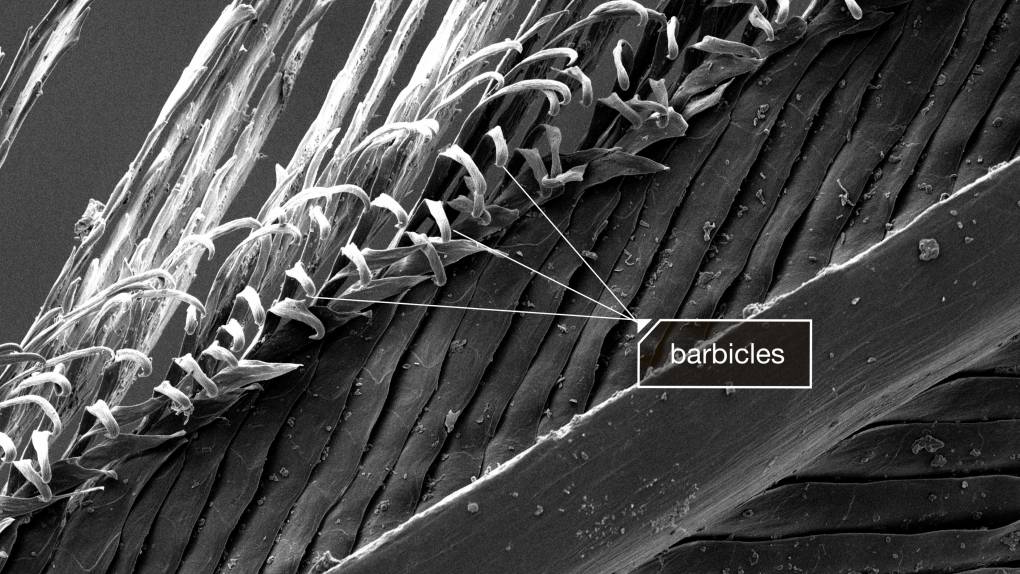

Every feather has a central hollow shaft, known as the rachis, and a flat area known as the vane. The vane is made up of hundreds of branches known as barbs. Branching from these barbs are structures known as barbules, some of which are tapered with tiny hooks known as barbibcles.

Unlike down feathers, contour feathers are loaded with barbicels that interlock the neighboring barbs together like Velcro to form a wind and water-resistant barrier.

The strain of flight and locomotion can sometimes force barbules out of alignment. When this happens, the vane of the feather splits, allowing air and water to pass through. To prevent this from happening, birds tend to their feathers regularly, in a process known as preening.

Birds preen by brushing their feathers with their bill. This process allows birds to keep their feathers clean, smooth, and free of parasites.

Having well-groomed feathers grants all birds some degree of water resistance, but aquatic birds take it to another level.

According to a 2016 study by scientists at the University of Debrecen in Hungary, aquatic birds like ducks and geese not only have feathers with denser, more tightly knit microstructures than their terrestrial counterparts, but they also have more of them.

“In aquatic species, the density of the feathers is much, much greater than in terrestrial species of similar body size,” said Orsolya Vincze, a research fellow at the Hungarian Academy of Sciences who helped conduct the study. “The barbule density is also much higher.”

Having super-dense plumage makes aquatic birds far more water-resistant than their terrestrial cousins, but it doesn’t make them waterproof.

To achieve that, aquatic birds coat their feathers with an oily substance known as preen oil, which is secreted from a gland on their rumps, above their tail feathers. This gland, known as the uropygial or preen gland, is present in nearly all birds, but its shape and size varies among species.

According to Dumbacher, aquatic birds tend to have much larger and more developed preen glands than terrestrial birds, which isn’t surprising because “they have to apply oil more regularly,” he said.

When preening, birds rub their beaks against their preen gland to collect oil and then rub it over their feathers. The oil from their preen gland coats the interlocking barbules of their feathers, rendering them waterproof.

It’s hard work. Some species will spend up to 25% of their waking hours preening.

However, preening isn’t just about waterproofing. Preening also rids birds of parasites and moisturizes their feathers so they can stay flexible, strong, and ready for flight.

Although the dense microstructure of their feathers and applying copious amounts of preen oil each help insulate aquatic birds from the elements, “it’s really the combination of the two,” that allows them to stay warm and dry even in the chilliest of ponds, said Dumbacher.

If you want to see the wonder of waterproof feathers in person, Dumbacher recommends heading down to your local pond to watch some ducks.

“It’s fun to see how water just flips off the back of a duck,” Dumbacher said.