As the COVID-19 virus continues to spread around the Bay Area and the world, the National Institutes of Health says a vaccine for the public is at least a year away. Still, researchers around the world are already working on it, and some clinical trials have begun. To learn about the latest efforts, KQED’s Brian Watt visited the Gladstone Institute of Virology and Immunology, a nonprofit research center in San Francisco. He spoke with Senior Researcher Dr. Melanie Ott.

Ott’s answers have been edited for length and clarity.

What is a virus and how does it infect our cells and spread around the body?

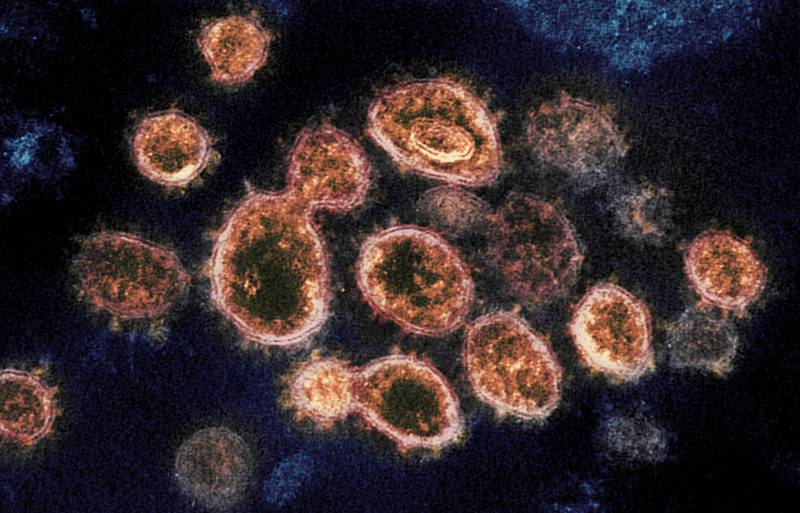

A virus, to a virologist, is a fascinating little creature. It is basically a minuscule ball of proteins that contains in its shell a nucleic acid, which is the genome or the code for the virus to replicate. By itself, the virus is not able to propagate or to replicate or to multiply, and it needs to get into a host cell. Once it’s in the cell it can then hijack a lot of the proteins in our body and in our own cells to replicate itself. This is basically the only purpose of a virus.

On the other side of the equation, what is a vaccine?

If the virus comes into our cells, the cells are not going to be powerless, the cells are going to be highly alarmed, and our whole immune system is basically geared toward defending us against invading viruses or other pathogens.

So when the virus comes in, an immune reaction is being generated — T cells and B cells — and they produce things like antibodies that will recognize the virus, neutralize it, and get it out of the system.

What the vaccine does is activate this reaction of our body ahead of a virus coming in. We mimic what the natural virus would do, but instead of having to go through a whole infection and becoming sick, we do this with a nondangerous and easy means ahead of time. So our immune system is already prepared when the virus comes in, to immediately kick in and to eliminate that virus before we get sick.