The Legislature did not vote on a high profile plan to require manufacturers of single-use plastic to take responsibility for the fate of their products.

Industry groups lobbied hard against the bill, and supporters promised to push the measure next year.

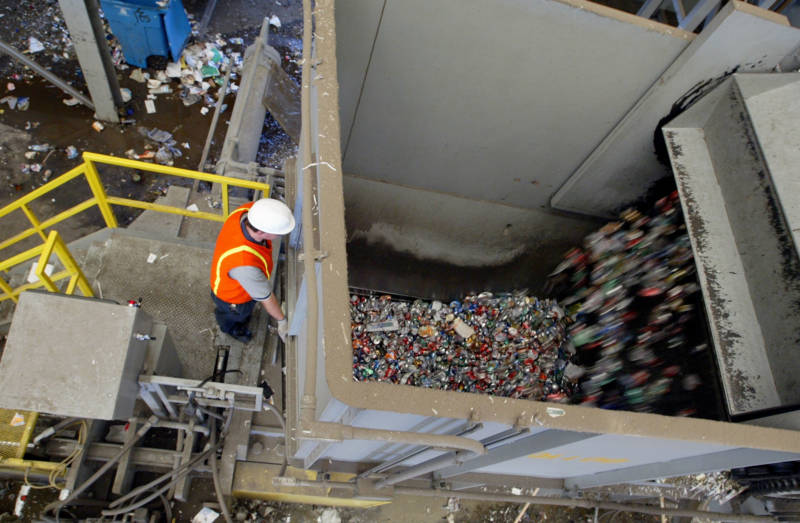

Recycling Center Closings

In August, rePlanet, California’s largest operator of recycling centers closed 284 facilities and laid off 750 employees. The shutdowns resulted in the state losing nearly a fifth of its redemption centers in a single day.

The company cited economic pressures, including the plummeting value price of aluminum and recycled plastics, as a reason for going out of business. In the past, recycling centers bundled materials and resold them, often overseas to China, but that country is now refusing much of the plastic from the U.S.

A powerful environmental advocacy organization on the issue of recycling, Californians Against Waste, opposed Ting’s plan. A memo from the group said the bill doesn’t address the root causes of recycling center closings.

Grocers and Recycling

California collects a 5 or 10 cent deposit that consumers pay on cans and bottles. Consumers who bring their used cans and bottles to recycling centers can get that money back, and the state uses these funds to pay for recycling programs.

California’s Bottle Bill from 1986 created half-mile areas around grocery stores where consumers can redeem their deposits (3 miles for rural areas). If a recycling center doesn’t exist inside of one of these convenience zones, then any business that sells soda, beer and other beverages in bottles and cans is mandated to take empties from consumers or pay a $100-a-day waiver.

The closure of recycling centers created an issue for stores that were not prepared to absorb people’s bottles but were suddenly required to do so.

With Ting’s plan, grocers won’t have to pay the fee until March 1, 2020.

The California Grocers Association supported Ting’s proposal. Ron Fong, the group’s president and CEO, said the state’s recycling system is outdated and needs to be fixed. He hopes the mobile recycling centers will give people more opportunity to redeem their deposits.

“A hundred dollars a day is onerous and small grocery stores cannot afford to pay it,” he said. “It’s not the grocers fault that rePlanet decided to close the centers, but we are left holding the bag. This gives us a reprieve.”

But, consumer advocates have long criticized big grocers for not accepting recycling, even before rePlanet shuttered all its recycling centers in August.

In May, Consumer Watchdog surveyed 50 Los Angeles-area businesses, including Rite Aid, Ralphs, Vons, Pavilions, Albertsons, and others, and found that two-thirds of the companies refused to redeem the deposits they are legally required to.

The legislative deadline for lawmakers to introduce new bills passed months ago, but Ting removed the text of different, unrelated bill and rewrote it, a procedure called gut-and-amend.

Jamie Court, president of Consumer Watchdog, says the bills amount to a corporate giveaway because they would release retail stores from their legal recycling requirements.

In an editorial published in the Sacramento Bee, Court argues that Ting’s bill is filled with “rotten scraps of failed legislation the grocers lobby packed into” a last-minute bill.

She argues that Californians pay $1.5 billion each year for bottle and can deposits, but they only get about half of that money back. When no recycling centers are close, grocers should be the ones that redeem. “Too often,” she said, “they don’t.”