This Bee Gets Punched by Flowers for Your Ice Cream

Sure, cows are important. But next time you eat ice cream, thank a bee. Without them, there would be no cones, milkshakes or sundaes.

Every summer, alfalfa leafcutting bees pollinate alfalfa in an intricate process that gets them thwacked by the flowers when they release the pollen that allows the plants to make seeds. The bees’ hard work came to fruition last week when growers in California’s Kings, Fresno and Imperial counties finished harvesting the alfalfa seeds that will be grown to make nutritious hay for dairy cows.

The bees’ work “is ice cream in the making,” said Shannon Mueller, who helped introduce the pollinators to California in the early 1990s and recently retired as director of the University of California Cooperative Extension in Fresno and Madera counties. “A vast majority of the forage goes to dairy cows.”

Alfalfa hay is also fed to beef cattle, sheep, goats and horses. California is the top alfalfa hay and dairy producer in the U.S., as well as the country’s top alfalfa seed grower. This year’s crop of approximately 18 million pounds of seeds will be sold in California and Arizona and to countries such as Saudi Arabia, Mexico and Argentina, which have similar climates to the state.

Alfalfa leafcutting bees are second only to honeybees in their value as crop pollinators, said biologist Theresa Pitts-Singer, who studies the bees at the U.S. Department of Agriculture in Logan, Utah. And when it comes to pollinating alfalfa, they leave honeybees in the dust.

This is how it works.

To produce alfalfa seeds, farmers let their plants grow until they bloom. They need help pollinating the tiny purple flowers, so that the female and male parts of the flower can come together and produce fertile seeds. That’s where the grayish, easygoing alfalfa leafcutting bees come in. Seed growers in California release the bees – known simply as cutters – in June and they work hard for a month.

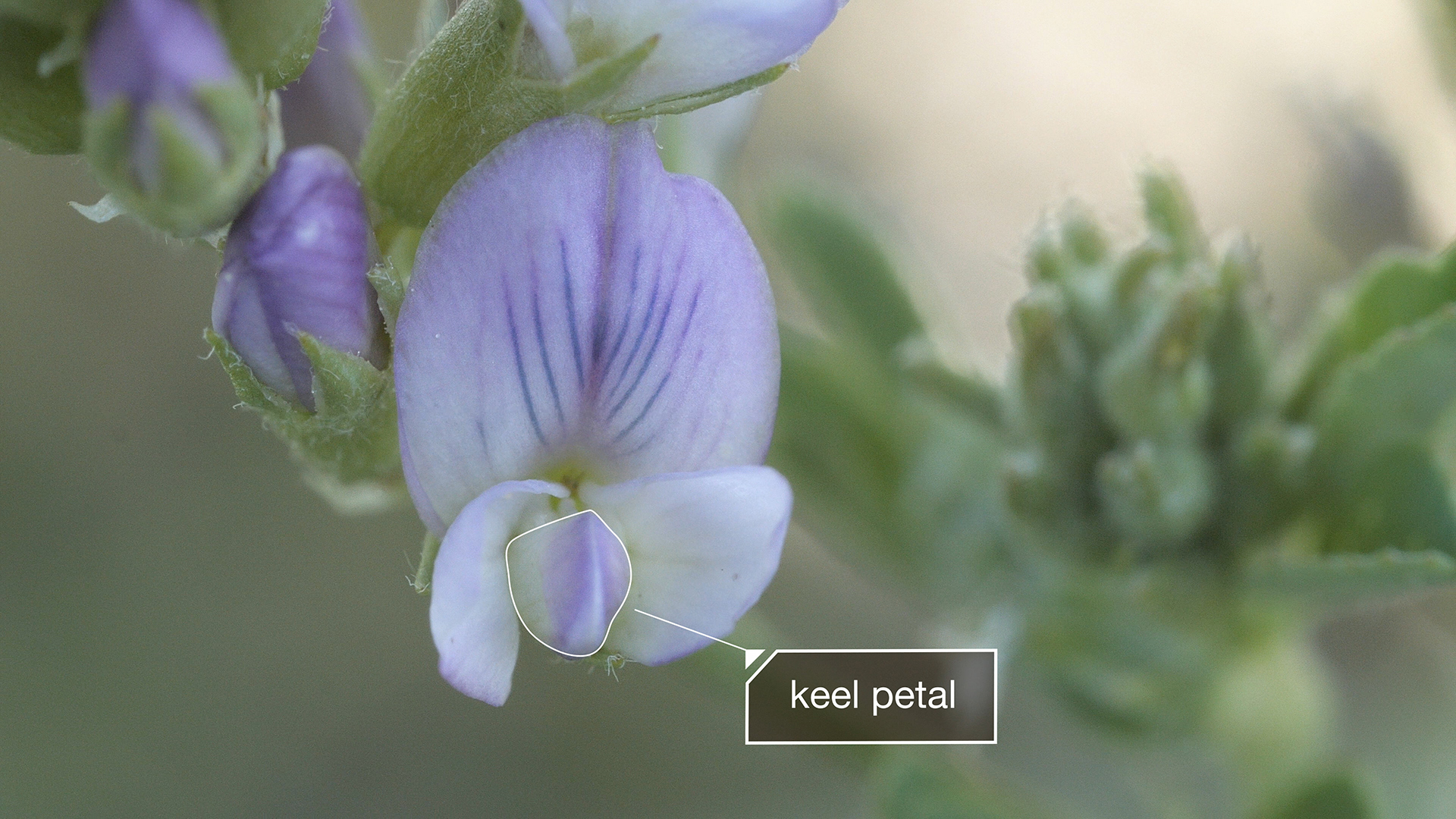

Alfalfa’s flowers keep their reproductive organs hidden away inside a boat-shaped bottom petal called the keel petal, which is held closed by a thin membrane that creates a spring mechanism.

Cutter bees come up to the flower looking for nectar and pollen to feed on. When they land on the flower, the membrane holding the keel petal breaks and the long reproductive structure pops right up and smacks the upper petal or the bee, releasing its yellow pollen. This process is called “tripping the flower.”

When the flower is tripped, pollen falls on its female reproductive organ and fertilizes it; bees also carry pollen away on their hairy bodies and help fertilize other flowers. In a few weeks, each flower turns into a curly pod with seven to 10 seeds growing inside.

Cutters were “game changers” in the alfalfa seed business because they’re much better at pollinating alfalfa than honeybees are, Mueller said. Cutters trip 80 percent of flowers they visit, compared to honeybees, which only trip about 10 percent.

“Honeybees don’t like to be flipped in the face, but it doesn’t bother the leafcutter bees,” said Chuck Deatherage, a grower who uses both kinds of bees to pollinate about 1,000 acres of alfalfa seed fields that he farms with two business partners in the Fresno area.

Honeybees sip nectar from the side of the flower rather than from the front, where they would trigger the keel petal, said Pitts-Singer.

And honeybees will visit alfalfa flowers that have already been tripped by cutters; by doing this they help spread pollen around.

“The honeybees follow the leafcutters to get the nectar,” said Deatherage. “That’s my theory.”

Because they work well together, growers release both honeybees and cutters. In an alfalfa seed field, you might see 10 to 20 honeybees and 20 to 50 cutters in a 3-foot radius, he said.

Deatherage buys the bees in Styrofoam nests and keeps them refrigerated for most of the year so that they don’t fully develop. As his alfalfa fields get near to blooming, he warms up the developing bees in their nests to close to 85 degrees. When they start hatching two to three weeks later, he stacks the boards into rectangular structures that sit inside trailers in the alfalfa fields and have the appearance of bee apartment buildings.

Alfalfa leafcutting bees are solitary — each female builds its own nest. But unlike other solitary bees that like to work in isolation, cutters don’t mind working side by side with other bees, said Mueller.

“This is to our advantage,” she said. “We can put large populations of leafcutter bees together in the field.”

The bees carefully cut out discs of alfalfa leaves or other leaves or petals they can find nearby. They fly with the piece curled up under their abdomen, held between their legs, to a nest hole in one of the Styrofoam boards and maneuver their way in. But it’s tricky.

“You’ll see piles of debris in front of the nest opening where they’ve dropped a leaf piece,” said Mueller. “I used to think, ‘Oh, all the work that went into all these dropped leaf pieces.’ ”

Inside its nest hole, the bee shapes several leaf pieces into a cell, where she lays a single egg on a ball of pollen she has collected.

“They look like a medicine capsule made of leaf pieces,” said Mueller, “and inside each of those capsules there is a developing bee.”