It’s not just skiers who have been whipsawed this season between fear of another dry winter and delight over the epic January snowfall in the Sierra Nevada.

Also paying close attention: water wonks.

Why? Because melting Sierra snow provides somewhere between one-third and one-half of California’s water supply. What determines just how much water is derived from that snow is called the “snowpack.”

As of this week, water stored in accumulated Sierra snows was running just about average for late January, and amounted to about 60 percent of the average on April 1, when the snowpack is typically at its peak for the year. “Average” is good news compared to where things stood less than a month ago, when the snowpack was only about two-thirds of the early-January average.

“We can really make up a lot of ground if we just have a couple of kind of heavy-hitting storms,” says Ben Hatchett, a snow watcher at the Desert Research Institute in Nevada. “And we sure did, and the people rejoiced — both at the ski resorts and hopefully at the water management and other agencies.”

So What’s the Snowpack?

The term snowpack refers to the amount of snow on the ground at a given time. When scientists measure snowpack, they’re typically concerned with the Snow Water Equivalent (also known as Snow Water Content). The Snow Water Equivalent is how much water, measured as depth in inches, would be produced by melting the snow.

Thus, the Snow Water Equivalent, or SWE, takes into account a particular snow’s density, and it can vary widely: Colorado’s powder may be luxurious for skiers, but because it’s less dense it contains less water. Meanwhile, the snow that skiers call “Sierra cement” is much denser and thus full of water.

The California Department of Water Resources and other organizations monitor the snowpack by conducting monthly snow surveys, which help inform projections of the state’s water supply.

In this video, KQED Science Editor Craig Miller ventures into the Sierra with veteran state surveyor Frank Gerhke, to see how traditional manual snow surveys are taken.

Timing: It’s Everything

UC Merced hydrology professor Rogers Bales has been studying the Sierra Nevada snowpack for roughly three decades. He says the importance of the snowpack comes down to its functioning as storage.

“Most of California’s precipitation comes during the cold, wet season when the crops and forests don’t need as much water,” Bales explains. He notes that farmers use 80 percent of the state’s water supply. “[They] need a lot of water in the summer, when there’s very little or no precipitation.”

And that’s where the snow comes in. Its natural ability to store water is why the Sierra snowpack is often referred to as California’s “frozen reservoir.” As spring sets in, the snowpack begins to melt. Water that’s not absorbed into the ground, called“runoff,” trickles into mountain streams, which feed rivers and eventually aqueducts and reservoirs, where it can be stored for use throughout the dry season.

So timing is everything when it comes to the melting of the snowpack.

“We want the runoff to be as late as possible, as close to when we need it as possible,” Bales says.

Typically, that runoff begins in April, and in wet years, it can continue to flow through August, according to Bales. But in years with less precipitation, and therefore less accumulation of snow, the runoff can wind down as early as May. That leaves farmers with less reserves for those dry summer months.

Another concern, Bales says, is runoff that comes too early, triggered by warmer temperatures and rains over the mountains during winter months. Runoff occurring before April has the potential to cause flooding downstream. In February 2017, storms caused the equivalent of a full season’s runoff in the Feather River watershed to pour into Oroville Reservoir, in Butte County. Ultimately, attempts to release huge volumes of water through Oroville Dam caused both the main and emergency spillways to collapse, forcing evacuation orders for 100,000 people.

The Future: Warming Temperatures Mean a Smaller Snowpack

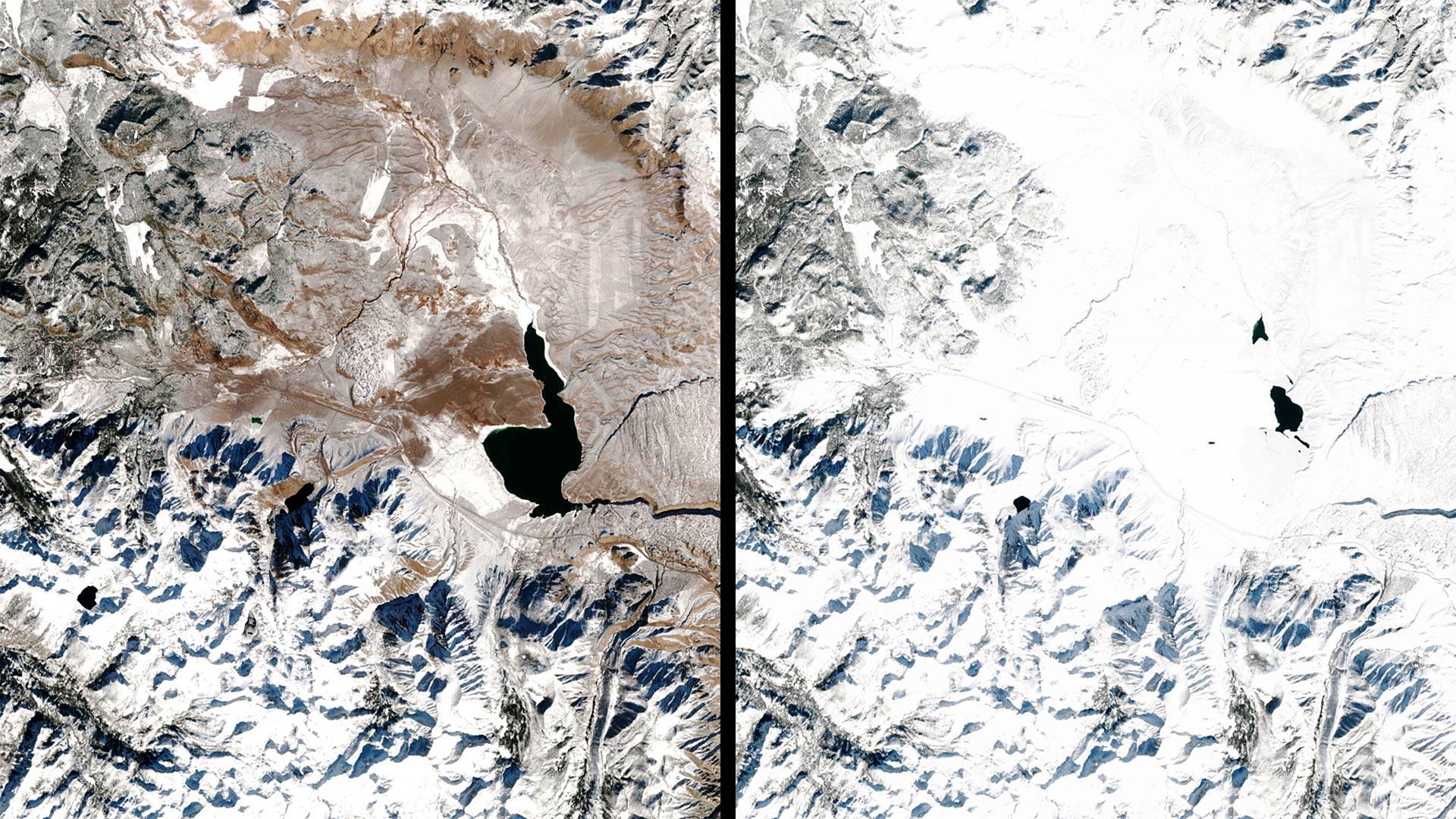

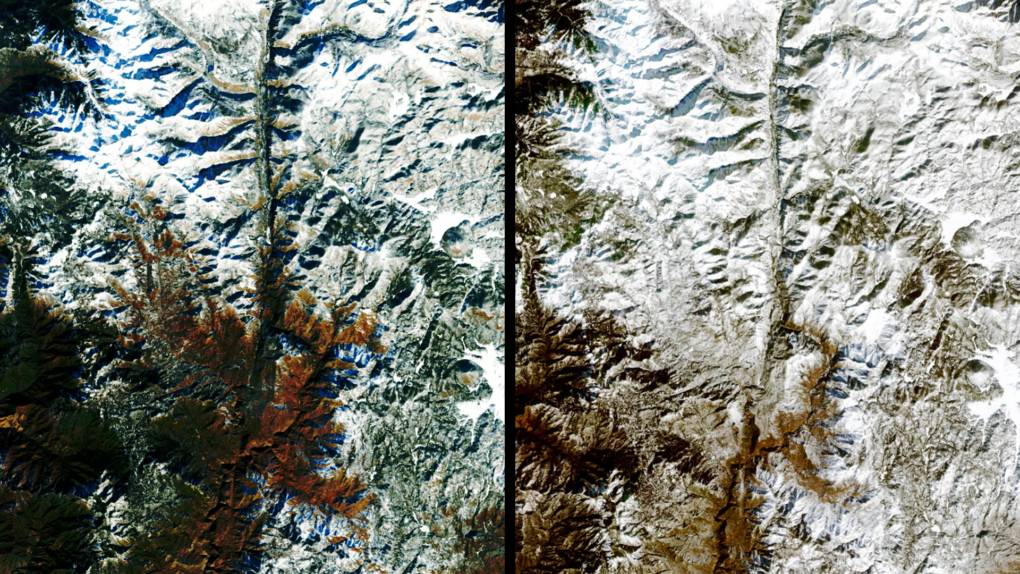

The warming climate is already shrinking California’s “frozen reservoir.”

Over time, temperatures in the mountains are rising, leading to more “rain-on-snow” events, when warming temperatures cause it to rain where there’s already snow on the ground. That accelerates the melt, which produces runoff that’s out of sync with California’s seasonal water needs.

The accepted rule of thumb, according to Bales, is that for every two degrees Celsius (3.6 F) of increased surface temperature, the snowline will rise 1,000 feet in elevation, which makes for a kind of double-whammy.

“You’re getting rain instead of snow,” says Bales, “and [the snow is] melting earlier.”

This is not just speculation, according to Alan Rhoades, a climate modeler with Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. He says that climate change has already begun to impact the Sierra snowpack.

“We have had roughly about a one-degree Celsius [1.3 F] increase over the last 50 years in the Western United States in terms of surface temperature.” Rhoades says. “And so the timing [of runoff] has been shifting earlier and earlier.”

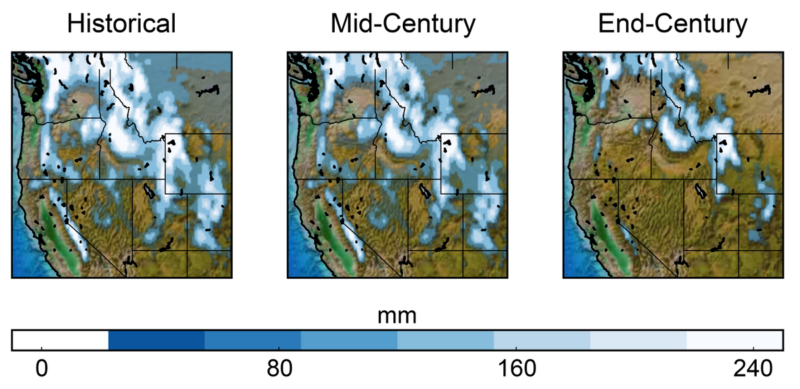

Research conducted by Rhoades and colleagues published in Geophysical Research Letters predicts that more than three-quarters of the snowpack in the Sierra Nevada could be gone by the close of the century.

“Most of the climate modeling scenarios that I’ve seen predict about a 30 to 60 percent decline by mid-century in average snowpack in winter months,” Rhoades says. “By the end of the century that ramps up to about 70 to 80 percent.”

But, Rhoades says, this forecast is not set in stone. His projections are based on a “high-emissions scenario” that contributes to surface warming. In other words, it assumes minimal progress in reducing warming emissions like carbon dioxide and methane.

On the flipside, if the world succeeds in making drastic cuts in climate emissions, the picture needn’t be so grim.

The 2018-19 Season

About half California’s annual precipitation typically falls within three months, from December through February. After an eerily dry November — the first storms didn’t roll in until nearly Thanksgiving — the January storms have more than made up for lost time, with an atmospheric river storm dropping several feet of snow on the Sierra and pushing the statewide snowpack to above normal: 103 percent of average, as measured on Jan. 17, versus just 67 percent on Jan. 3.

The next snow survey is scheduled for Feb. 1. Despite the good season to date, water wonks and worriers will be keeping a close tab.