Want a Whole New Body? Ask This Flatworm How

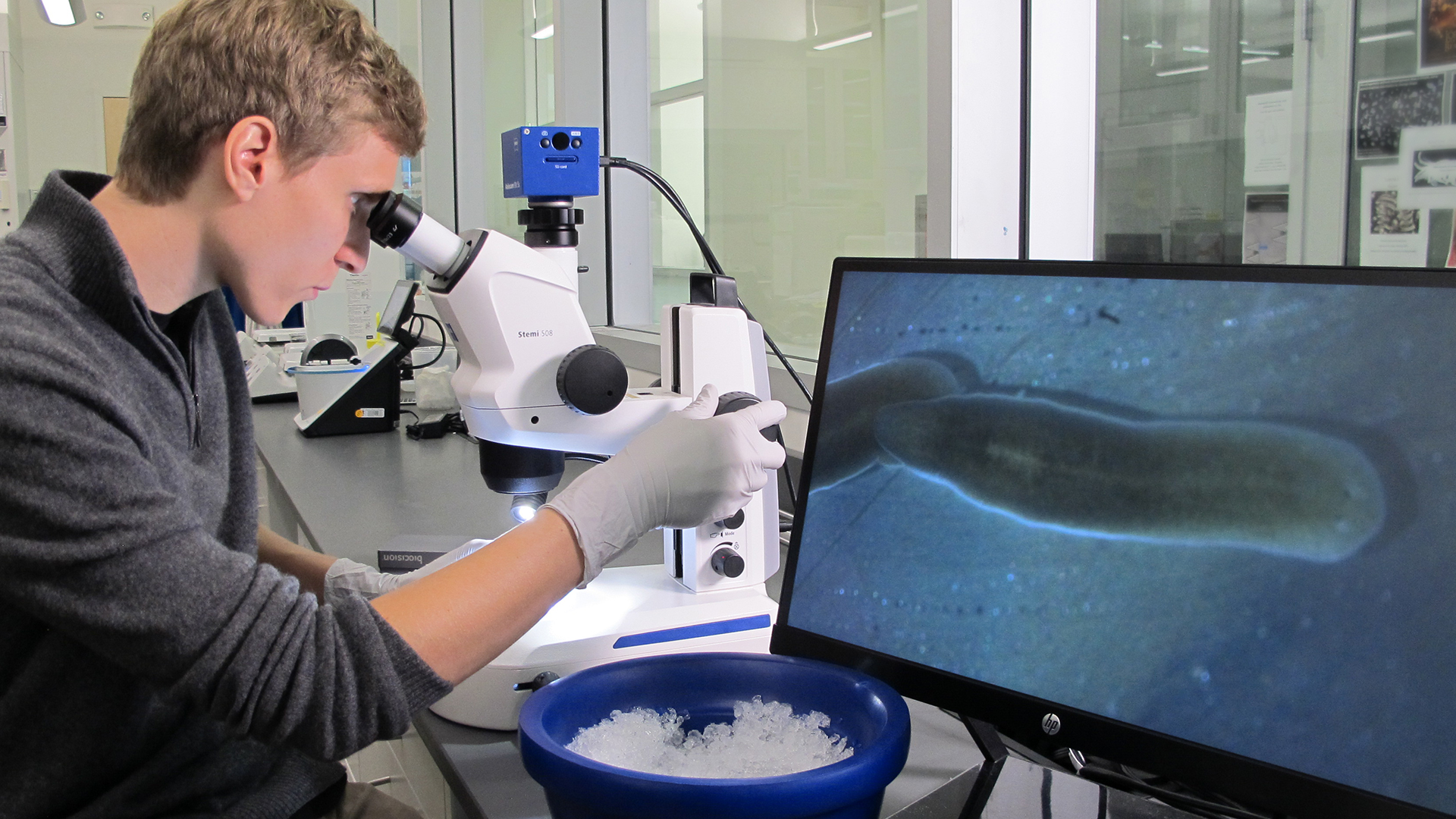

Nelson Hall wants you to know that the googly-eyed flatworm he just sliced into four pieces is going to be OK. In fact, it’s going to be great.

Three of the flatworm’s four pieces have started to wriggle away from each other; its head is moving in circles under Hall’s microscope.

“The head will just go off and do its own thing,” said Hall, a doctoral student of bioengineering at Stanford University.

But in three weeks, the head, as well as the other pieces, will each have grown into a complete flatworm just like the one Hall sliced up, dark brown and about a half-inch long.

Hall and researchers around the world are hard at work trying to understand how these flatworms, called planarians, use powerful stem cells to regenerate their entire bodies, an ability humans can only dream of. When we suffer a severe injury, the best we can hope for is that our wounds will heal. But our limbs don’t grow right back if they are cut off, the way that planarians do.

“Healing is more like closing the wound and cleaning debris. It’s too short of a process to have tissue replacement,” said Hall. “Regeneration is replacing the tissue that was lost.”

Other animals like starfish, salamanders and crabs can regrow a tail or a leg. Planarians, on the other hand, can regrow their entire bodies — even their heads, which only a few animals can do.

Key to planarians’ regenerative ability are powerful cells called pluripotent stem cells, which make up one-fifth of their bodies and can grow into every new body part. Humans have pluripotent stem cells only during the embryonic stage, before birth. After that, we mostly lose our ability to sprout new organs.

“We have a couple of tissues that can regenerate, like the liver, the outer layers of the skin and the inner layers of the intestine, and the bone marrow,” said Dr. Stephen Badylak, deputy director of the McGowan Institute for Regenerative Medicine at the University of Pittsburgh. “But the way we heal most tissues is by forming scar tissue.”

Scientists hope that studying planarians could lead to treatments for humans in which our stem cells could be coaxed one day to regrow severed limbs or sick organs.

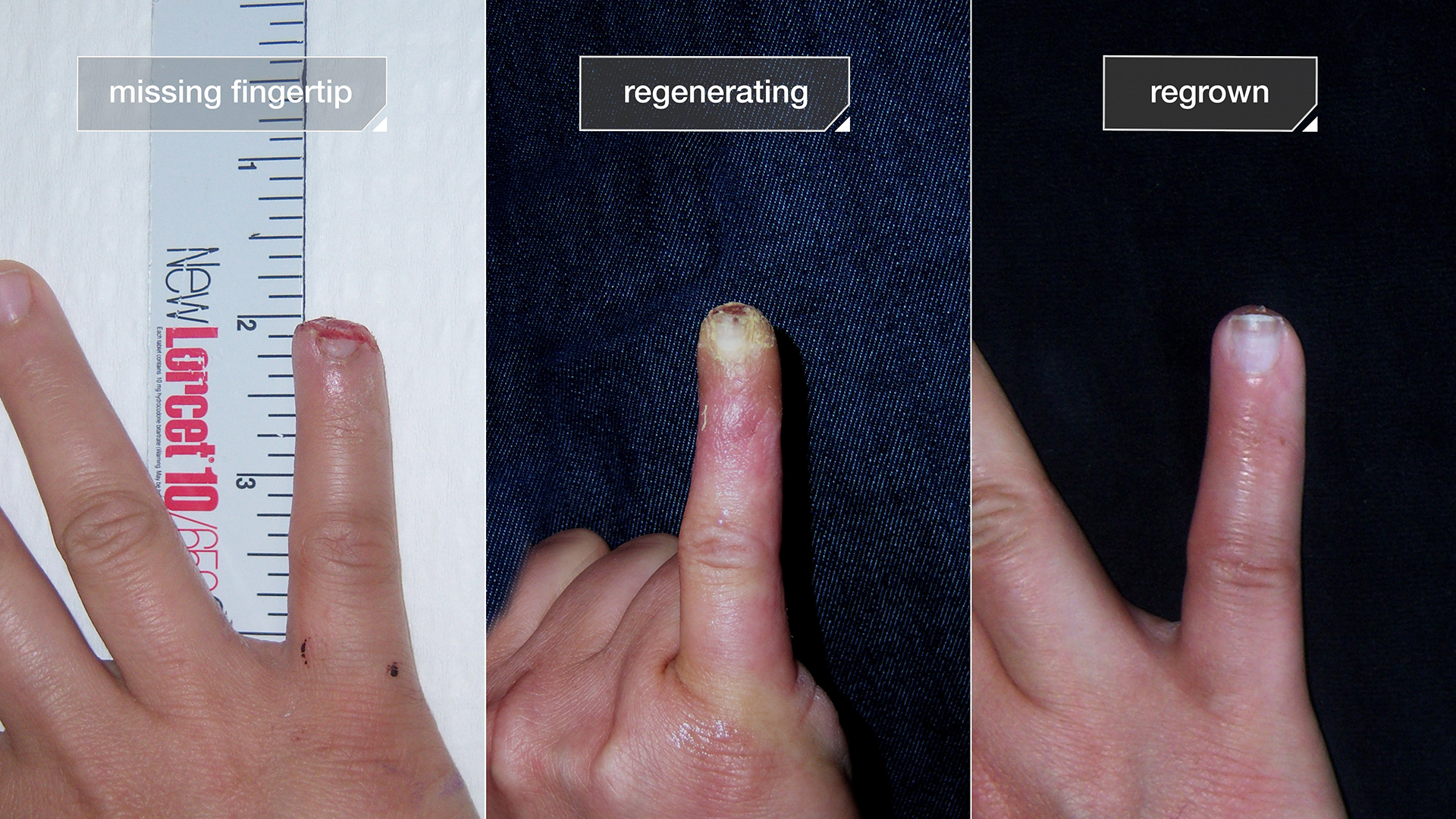

Doctors are limited in what they can currently do to help people who lose a limb or part of one. Badylak, who doesn’t study planarians, has developed a treatment at the University of Pittsburgh that helps patients regrow their fingertips after an accident.

He applies a powder made of animal collagen and substances that stimulate cells to grow, to help form a scaffold that attracts stem cells from the parts of the nail bed that weren’t cut off. The stem cells regrow the fingertip, which isn’t identical to the one that was cut off but is functional.

Dr. Badylak and his team also have been able to help patients regrow 30 to 40 percent of the muscle they lost after catastrophic injuries caused by roadside bombs or motorcycle accidents. He said much more could be done with increased knowledge about stem cells, and he’s excited by what scientists are learning about planarians.

“There’s a tremendous amount to be gained by comparing the genes of regenerative species and non-regenerative species and seeing where the similarities and the differences are,” Badylak said.

At Stanford University, Hall is working to make a green fluorescent planarian, one that would be genetically engineered with a protein to glow green under a certain type of light. This would allow researchers to insert different genes into planarians and study what the genes do.

“How do we genetically modify these worms so that we can put in our own genes,” asked Hall, “or remove existing genes to better understand how their regenerative programs function?”

A chunk of planarian with no tail and no head can regrow both in three weeks, and the process is astounding to watch.

In one week, two tiny little spots appear on the piece of planarian: new eyes grown from scratch. But the planarian, if you can call it that yet, still looks like a blob.

By Day 12, it has grown a new head and a new tail, both of them translucent — they’ll turn brown in another week. By now, it can eat, using a white, muscly tube called the pharynx, which operates something like a vacuum cleaner, extending out of the planarian’s body and sucking up bits of food.

In the ponds and springs where they’re found, planarians feed on tiny animals and decomposing plants. But in the lab, they’re picky. Hall feeds them a beef liver paste, basically pate.

“It has to be organic, grass-fed calf liver,” Hall said.

Some kinds of planarians can use regeneration to reproduce without having sex. These asexual planarians break their bodies in two and grow a new planarian from each half. Within the same species there are also planarians that reproduce sexually, by laying eggs after mating.

“It’s the same species that does both, which is kind of a weird thing,” said biologist Dania Nanes Sarfati, a doctoral student at Stanford who is studying their sexual organs.

Researchers haven’t found much evidence that regeneration helps planarians regrow after an attack. Instead, they seem to dissuade predators with an uninviting slime that covers their bodies.

“In nature, they’re not being cut up into fragments,” said Ricardo Zayas, a neurobiologist who studies planarians at San Diego State University.

Zayas is studying how, after their heads are cut off in the lab, planarians are able to regrow dozens of types of neurons that help them detect their environment.

“How do they smell food, how do they feel touch?” Zayas said. “And the neurons that are responsible for doing that, how do they regenerate and how do they make them function?”

Scientists are trying to figure out exactly how planarians do it, and maybe one day these humble flatworms could inspire new ways to heal our injuries.

Allie Weill contributed reporting.