“To my child, I’m the most powerful people in her life,” Shrum said. “It’s my job to take care of her and do what I can to ensure she has a chance at a really great future.

“When it comes to being accountable to yourself, you can make excuses for why you don’t act on climate change. But any excuses you have to your child about why you didn’t do everything you could to protect them and their future is really, well, you can’t make those excuses. They fall flat.”

Writing a letter for her daughter to read in 2050 was a transformational moment in Shrum’s life and one she wanted to share with other people. She also knew that getting people to imagine a hopeful future for their children has the power to to disrupt how we view climate change, shifting it from an intractable problem to an opportunity to reshape our world.

That’s because Shrum has a PhD in behavioral sciences and economics and is currently a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Colorado. The project’s conception and execution is grounded in the science of how humans think and what it takes to get people to act on big problems.

When it comes to climate change, the big problem is that most people see it as a massive issue beyond their control. But having people write a letter to their future self or loved ones makes it personal. DearTomorrow also asks letter writers to focus on positive themes and why they have hope for future generations.

“It’s easy to get apocalyptic about climate change, but we want to deliver a message of hope and empowerment not one of doom and despair,” Shrum said. “We see that reflected in our letters. There are so many sentences that begin or end with, ‘I hope.’”

Social science research indicates that positivity has value as well. Per Espen Stoknes, a Norwegian psychologist who has studied why climate change is such a tough issue for humans to address, wrote an entire book on the topic.

In a 2015 interview with Yale E360, Stoknes said, “Rather than something distant, communicators need to make climate change feel like something that is near, personal, and urgent. Rather than doom, we need to emphasize the opportunities that the crisis affords us.”

DearTomorrow is betting on the power of individuals to amplify that message even further. The other important aspect of the project is bridging the tribal divides we’ve built up (you only need to look at your Facebook newsfeed this election season to see them firsthand).

While our tribal nature has the power to divide, it can also bring people closer together. And when the messages are deeply personal, they can actually move people. Though the letters are addressed to future generations, the people who write them are free (and in fact encouraged) to share them with their current social networks.

“The power of this project is that we find people need to hear information from people they trust and in language they understand from people like them,” Shrum said. “When you share your reason for taking action on climate change in your voice, people can relate to it in a way that they might not if it was from (climate activist) Bill McKibben.”

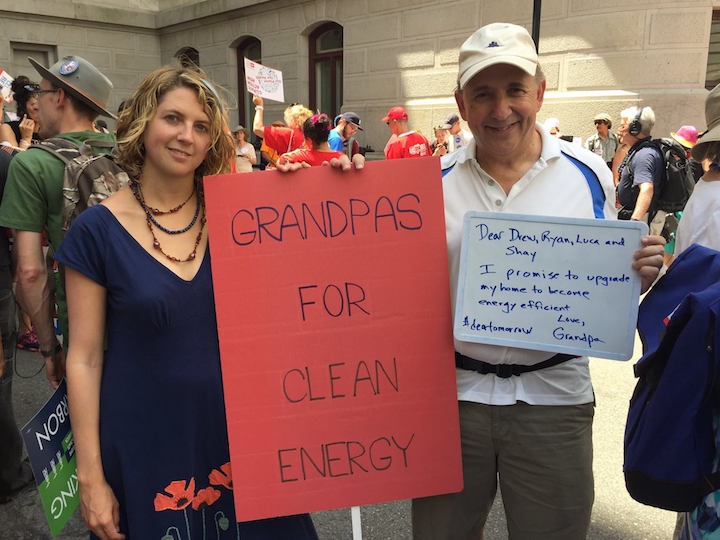

The project has attracted hundreds of letters from everyday people. Companies such as Virgin have also gotten on board with letters from company leaders to their children. Shrum said she eventually wants to provide people with ways to turn what’s in their letters into concrete, meaningful actions to address climate change.

The timing of DearTomorrow couldn’t be better when it comes to climate communication. A recent joint Yale and George Mason University survey found that the number of Americans who discuss climate change with family and friends has steadily dropped over the past eight years, creating what researchers call a “spiral of silence.” As fewer people talk about it, fewer people still feel comfortable bringing it up.

That dynamic has to change and the public will have to be more engaged than ever with climate solutions if the world is to cut its fossil fuel habit. The letters of DearTomorrow will provide a snapshot for historians not just in 2050, but beyond, of the cultural mood in one of the biggest periods of change in human history.

“Archivists think in centuries and preservation,” Shrum said. “This is a special moment in history and we want to preserve that conversation at a transition point and what it was like to live when there was this massive change from this economy driven by fossil fuels to this one driven by clean energy.”