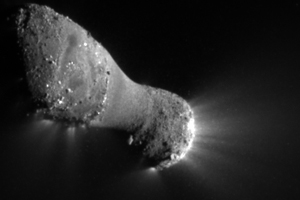

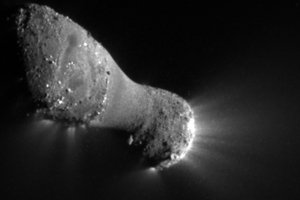

Comet Hartley 2 during the November 4, 2010 NASA/EPOXI

Comet Hartley 2 during the November 4, 2010 NASA/EPOXI

flyby missionThursday, November 4, 2010: the morning I got up, drove to work, poured my coffee, and whizzed past a mountain-sized chunk of space ice at a hair over 27,000 miles per hour. My job just never gets old….

If you were with us early that morning, you were one of a lucky and intrepid few to experience live the flight of NASA's EPOXI mission (aka the Deep Impact spacecraft) past the nucleus of tiny Comet Hartley 2—a comet that we had been watching through our telescopes for a few weeks. Live space exploration as a public experience is a rare and extraordinary opportunity, and we strive to share it with you whenever we can. Kudos to those who got up before 6:00 AM to join us.

EPOXI is the name for the extended mission of the re-purposed Deep Impact spacecraft, which you may remember lobbed a projectile at Comet Tempel 1 back in 2005. Since that encounter, the spacecraft has been orbiting the Sun, keeping itself busy with other observational activities, including looking for extra-solar planets. But the time had come, the orbital trajectories matched, for an encounter with Hartley 2, a smallish comet circling the Sun between the orbits of Earth and Jupiter. The EPOXI flyby was the fifth time in history that we have captured close-up images of a comet nucleus, and the first time a single spacecraft has bagged two.

What are scientists looking for by sending spacecraft to these distant space-bergs that they can't get with big ground-based telescopes, or the Hubble? In a word, details. From afar, we have observed comets for a long time, and can point telescopes at their nuclei, their comas (the shroud of gas they develop when the comets' ices are warmed in a pass by the Sun), and their long tails—yes, plural: comets typically develop two tails, one a trail of dust and the other a plume of gas, blown by the ever-present breeze of plasma from the Sun called the solar wind.