This piece was inspired by an episode of The Cooler, KQED’s weekly pop culture podcast. Give it a listen!

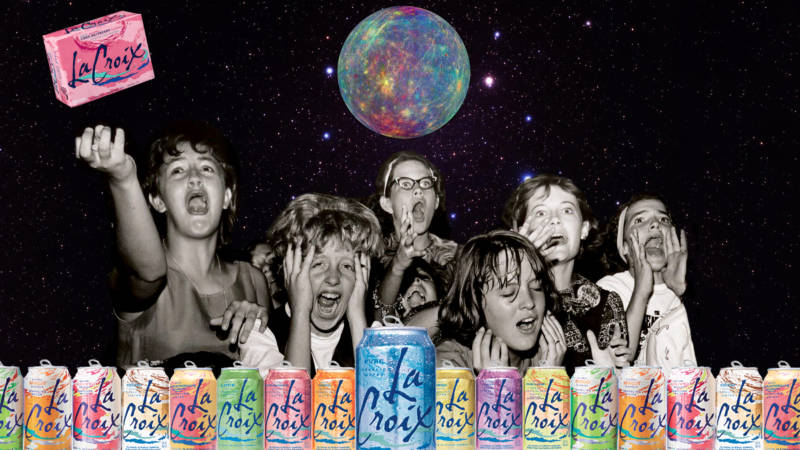

The Cult of LaCroix: Why Everyone's Gone Crazy over Canned Water

None of us drink enough water. Or at least that used to be true. In the last few years, a sparkling water brand called LaCroix has gained popularity, reaching fever pitch last summer as devotees wore LaCroixs Over Boys t-shirts; posed with their water cans on Instagram; flocked to see a fully-stocked wall of the stuff at the new Williamsburg Whole Foods; created their own can designs and flavors like "Male Tears" on mylacroix.com; crafted signature LaCroix cocktails like the Pina Croixlada; sold needlepoint art, enamel pins, and watercolors of the cans with "Can't Stop, Won't Stop" written underneath; and even penned rap songs about how great it feels to be sippin' on LaCroix.

This last example, by LaCroix fanatic RAKEEM, includes lyrics like "I know it's only carbonated water; sometimes I wish I was Beyoncé's daughter" and "When you're sippin' on LaCroix, you know it brings you joy."

So what's the deal here? Why are so many obsessed with water, of all things? Where did this brand come from? How do you pronounce it? I did some digging and found the answers to these questions and more.

How do you pronounce it?

First things first, how does one accurately pronounce the name? Based on the brand name's spelling, the inclination is to pronounce it the French way. For those who didn't randomly get a French minor in college like me, I'll use it in a sentence: Let them drink La-kwa! But the water doesn't come from a babbling brook in Provence. The water actually comes from... Wisconsin, and takes its name from that state's St. Croix River. And because Americans are heathens, it's pronounced La-croy.

Where and when was the brand created?

The brand got its start in a family-owned Wisconsin brewery back in 1981. It stayed local for many years, before being acquired by the National Beverage Corporation in the mid '90s. CEO Nick A. Caporella's strategy for making LaCroix a hit on a national scale? Redesigning the can with a retro, bright-colored look that's reminiscent of those paper dentist-office cups from the '80s. Quite the gamble, considering that the sight could trigger horrific memories of suction tubes and molar drills, but the new look was a hit.

What sets it apart from other carbonated drinks?

Eye-catching aesthetic aside, it's also what's inside the can that people love so much. In contrast to other brands that purport to be full of vitamins, but are mostly sugar, LaCroix loudly trumpets that it's free of sugar, calories, preservatives, artificial sweeteners, and sodium, instead opting for naturally-extracted fruit oils. (I realize this reads as if LaCroix is paying me to write this. Alas, I haven't received any coins from them, but if they wanted to turn my life into this Beyoncé gif, I'm down.)

Who were the LaCroix pioneers?

At first, the National Beverage Corp. marketed LaCroix to health-conscious women (data showed that men were mostly out-of-reach due to their preference for energy drinks). But, as distribution to all kinds of stores grew -- from co-ops and Wal-Marts to office supply stores -- more and more shoppers started picking it up — people on a diet, people trying to kick sugary colas or booze, people looking for a way to jazz up really old opened wine they forgot about in the fridge (this may or may not be about me), what have you.

Why has LaCroix become such a thing?

One major reason for the LaCroix boom is our culture's move toward better nutrition and embracing health-conscious lifestyles. Full-calorie soda sales (think Coke, the dearly departed Surge, or whatever "go-go juice" pageant moms give their children) have dropped more than 25% over the last 20 years. The average person in 1988 drank less than four gallons of bottled water per year. By 2015, that number shot to 37 gallons per year. Pee: now clearer and less stinky!

The wide array of flavors -- 20 in all, way up from only four in 2004 -- also contribute to the brand's success, because a) there's something for everyone, b) most of them taste good, c) it's much harder for consumers to get bored with the product, and d) there's a collect-them-all aspect to finding and tasting all the varieties.

Ironically, LaCroix also benefitted from coming out of a little-known parent company without much advertising muscle behind it. According to Forbes, National Beverage has 1,200 employees total, versus Pepsi's 264,000. The less-corporate, more-underground feel spoke to people, specifically hipsters who value the idea of authenticity.

LaCroix has also become somewhat of a status symbol, like SoulCycle or LuluLemon leggings. For some, it's less about enjoying the product and more about being a part of the movement and presenting an idealized cool version of yourself to the world (hydration becomes merely a side effect). LaCroix's Instagram contributes to this social performance by reposting flawless photos of peace-sign-waving, LaCroix-guzzling hipsters. Posting a picture of yourself drinking water isn't something most people would think to do, but add the potential promise of being a teeny tiny bit famous for a half day, and -- bam! -- an avalanche of LaCroix selfies, further spreading this idea of LaCroix being a signifier of "cool."

In a nutshell, the LaCroix craze is partly about the product -- it's healthy, it's cheap, it's easily available, it actually tastes good -- and partly about the social mythology that's been built around that product -- it looks cute and nostalgic, it feels cooler than overexposed big brands, it makes people feel hip. Whatever your opinion on LaCroix, you have to give the brand credit for achieving the impossible: making water popular. Next up: broccoli!

Hear more about what's behind our obsession with LaCroix (and mercury in retrograde) on this episode of KQED's weekly pop culture podcast, The Cooler: