Can we ever really find out who we are? That's debatable, but what is certain is that we sure do try. We pour over our astrological birth charts, trying to find answers for why we do what we do in the stars. Or we decide to backpack alone across some faraway continent to cross geographical boundaries and internal ones too. Maybe we get our auras read or cross reference our Myers-Briggs personality types with Harry Potter characters. And maybe we even spit into a test tube and hand over our DNA to some website like 23andme with a cute color scheme and hope they don't frame us for something.

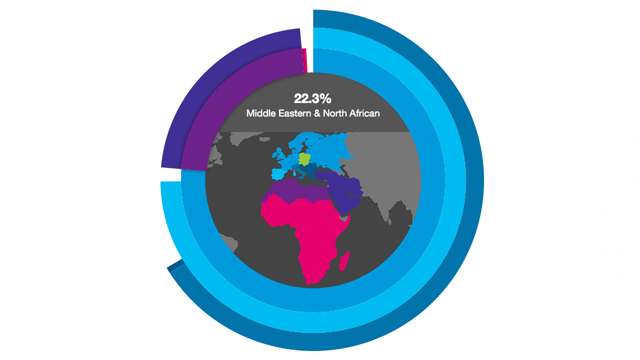

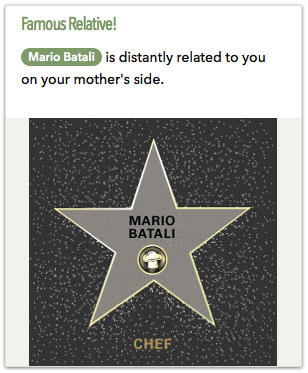

23andMe has been analyzing DNA samples sent in by customers for a mere $99 for the past few years, and providing insight into ancestry and health. You can find out the origins of your parents' genetics, which random celebrities you're related to, how much Neanderthal is in you, and whether you're really lactose intolerant or just a hypochondriac whiner. The Mountain View-based company, which was founded by Anne Wojcicki (wife of Google founder Sergey Brin), also proclaims that they can detect genetic susceptibility to diseases, a claim that led the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to order 23andMe to stop selling the product last month.

Whether this spells doom for 23andMe or proves to be just a speed bump has yet to be seen, but what's clear is that this desire to know more about ourselves and how we relate to others is something that has captivated our nation. Just think of the television shows (PBS' Finding Your Roots and TLC's Who Do You Think You Are?) that trace and sensationalize the genetics of random celebrities (Chelsea Handler's grandfather was a Nazi! Yo Yo Ma is related to Eva Longoria!). Not to mention social media, whose very foundation rests on assembling our identities and linking them to those that relate.

For centuries, there have been family trees (Confucius' is the world's longest and reaches as far back as 2,500 years); genetic testing is just a step further, one that leverages scientific and technological advances. In the olden days, one would learn about family history through word of mouth; one generation told stories to the next in their ancestral homes. It wasn't until immigration that this narrative chain was compromised. Now, when you ask someone where their ancestors came from, you'll get a vague response that sounds like an SAT math problem (a quarter of this, a sixth of that).