Grattan raised about $275,000, and that money “supports all or part of the salaries of about six staff,” Smith says.

Smith says that during the five years of cuts, instead of laying off employees, Grattan was “able to expand their staffing. They invested very wisely in academics, they were able to improve their standardized test scores and they created a school that people are really proud to be a part of.”

Across the city, Junipero Serra Elementary School, which has a predominantly Latino student population and where 90 percent of students qualify for free and reduced lunch “simply didn’t have the capacity to raise funds at the same level,” said Smith.

Smith’s research “found that a school’s poverty predicted its PTA budget.”

One listener described the concrete benefits of PTA fundraising:

“Without our PTA my kids would not have a music teacher, a PE teacher, a computer lab teacher, or new library books – hardly luxury items. So yes, I suppose PTA money does widen education inequality gap – by making some schools less dismal.”

Strong opinions on either side

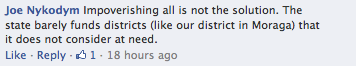

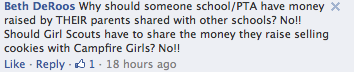

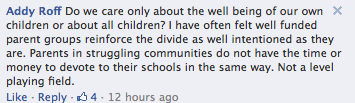

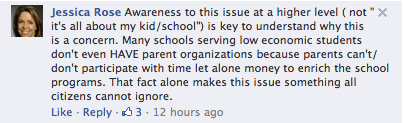

All of the guests applauded parents’ support for their children’s schools. Time and time again, the “Forum” conversation returned to the idea that all schools in California are underfunded and that ideally, parents would not be in the position of making up for state funding. However, listeners’ opinions differed greatly on how big of a problem the difference in fundraising abilities were — especially the idea of sharing funds with a districtwide pot, as occurs in Albany Unified School District.

Empowering All Parents

Several possible solutions outside of increased state funding did surface throughout “Forum’s” conversation. Carol Kocivar, the immediate past president of the California State Parent Teacher Association, mentioned an effort called School Smarts to educate parents:

“One of the things the state PTA has been involved in is creating parent academies, where parents are invited into the school and are given skills and resources to understand how the school system works. Because, as we know, we have a lot of parents who are new to the United States, or didn’t finish high school or go to college and give those parents the skills and resources to be advocates for their kids.”

Another possible solution proposed was having well-to-do, more established PTAs partner with those at schools with lower-income families. Smith said that was “something so fundamental and direct that we can do right now, which is to build bridges between these different PTAs, with these different cultures.”

Two commenters who identified themselves as having children at schools that raise a lot of money supported this buddy system of funding.

A commenter named Mark cited the ability of a few parents at his school to rally and lead the fundraising charge. He said, “We should be helping more parents at more schools learn this kind of leadership, because we will never be completely able to rely on city or state support.”

Another listener said:

“Just a half-hour walk away from my son’s school is one of the schools with no PTA at all, and a very low-income population. Perhaps our PTA (which is very well organized and well supported by the parents) could help them.”

Educational foundations

Keeping with the schools-helping-schools theme, the idea of educational foundations came up several times. One caller shared his experience with a foundation in Redwood City: “I’m part of the Redwood City Educational Foundation. … In our district, which is similar demographically to San Francisco, instead of 17 schools going out to try to raise money from the community, we speak with one voice and we go out to the community.”

And Laura wrote in to say: “Please tell your listeners to take a look at what has happened through the Ravenswood Education Foundation in East Palo Alto. It’s a parent foundation supported significantly by both parents within the district and their wealthier neighbors to the West.”

Wider community involvement

That appeal to the wider community was touched on several times throughout the show. Callers and guests alike said that schools need to convince the wider community — not only parents — that investment in schools is worthwhile. Carol Kocivar said, “One of the things that schools and school districts need to do is emphasize the importance that these are community schools. This is our community.”

Norton said, “You have to show (the community) what’s going on in public schools … what are some of the wonderful things happening in our schools.”

A larger issue

Robert Reich, professor of public policy at UC Berkeley’s Goldman School of Public Policy and a former U.S. secretary of labor under President Clinton, said the school equity question will linger as long as America’s larger equity issues continue:

“Children are being segregated geographically by income more than ever before — where you live has a direct bearing on the quality of education and other public services you are going to get …. And because families and children are segregating by income, that almost inevitably means that poor kids are going to get the short end of the stick. I think therefore one of the most important things we can do in terms of public policy is reverse and reduce the trend toward segregation by income, by neighborhood ….

“Being rich in America increasingly means not having to come across anybody who is not, and that really undermines the sense of empathy, and connection and social solidarity.”

Still not enough funding