Episode Transcript

This is a computer-generated transcript. While our team has reviewed it, there may be errors.

Morgan Sung, Host: You may have heard this one warning over and over recently. AI is bad for the environment. It’s using up all our clean water. It’s draining the power grids. It’s polluting our one precious world. But how? Let’s start with a video that fooled me a couple of months ago: bunnies on a trampoline. This video has like 250 million views on TikTok.

[Bouncing sounds]

Morgan Sung: This is a nighttime video, so it’s pretty dark and grainy. It looks like it could be in some suburban backyard. We see six or seven curious rabbits hopping onto the edge of a trampoline. Three of them move bravely toward the center and test a few jumps. Suddenly, all of the bunnies are bouncing up and down. It’s absolutely delightful. I mean, it’s bunnies on a trampoline. The person who posted it said they caught this moment on their ring camera. But my delight was cut short when I realized that one of the bunnies disappeared midair. The entire video was AI generated.

According to researchers, one five-second video, like this one, generated using one of top-of-the-line open source AI models, uses about 3.4 million joules. Joules are the standard unit to measure energy. I’ll say that again. One five-second video uses 3.4 million joules to generate. Now, what does that mean to the average person who probably doesn’t measure their day in joules? Well, MIT Technology Review published a report on AI energy use. For that report, Casey Crownhart, who covers the climate, and James O’Donnell, who covers AI, did the math to translate that energy usage into something accessible. Here’s Casey.

Casey Crownhart, Guest: One thing we really set out to do with this project was be able to answer that question for people who are using AI in their lives and wanna really understand what the energy footprint looks like. So we looked at a lot of things in our story. We also used distance on an e-bike, light bulbs, electric vehicles, but we found that the microwave was something that most people have experience with and it was units that sort of made sense.

Morgan Sung: As part of this project, Casey and James worked with researchers to figure out how much AI generation really costs in microwave time. So that video of the bunnies on the trampoline, let’s say that five second video cost 3.4 million joules. That’s the equivalent of running the microwave for about an hour. You can get 30 bags of popcorn out of that if you’re lucky.

The video of the bunnies on the trampoline was just one of dozens of AI-generated videos that I happen to scroll by every day. There are the videos of cats playing the violin, the physically impossible firework shows that my older family members keep sending the group chat, the many totally inappropriate videos of deep fake celebrities, the Facebook slop bait of animals rescuing old people from natural disasters, the AI- generated influencers shilling drop shipped products. Like, I could go on forever.

The reality is that all of this content that’s being generated, seemingly 24-7, comes at a huge cost, energy-wise. Slop is literally draining our resources. And that’s not even accounting for the constant ChatGPT queries or the flood of image generation prompts every hour of every day, and that is only what we see produced by AI. There’s a lot going on in the backend that also takes up a ton of energy.

Casey Crownhart: In our reporting, we found that, you know, those different use cases that can come with very different energy footprints. If you add it all up, ultimately, it can be significant. It’s probably a relatively small part of your total energy footprint, but it is definitely something that I think people are right to be thinking about in this new age.

Morgan Sung: Concern is growing about AI’s toll on the environment. And yet, AI companies would have you believe that their products are indispensable and that their impact is manageable. So, what’s the truth? How do we know what to believe? And what, if anything, should we do about it?

This is Close All Tabs. I’m Morgan Sung, tech journalist and your chronically-online friend, here to open as many browser tabs as it takes to help you understand how the digital world affects our real lives. Let’s get into it.

Casey and James spent six months crunching the numbers to give us some real world comparisons for the amount of energy it really takes every time you type up a prompt. This was actually more complicated than it seems. The companies that run the most popular models aren’t the most upfront about the numbers. So the stats that we do have are based on the AI companies that are a bit more open. Casey and James worked with researchers at the University of Michigan’s ML Energy Initiative as well as researchers at Hugging Face’s AI Energy Score Project. Hugging Face is a platform that allows users to share AI tools and data sets. With the help of the researchers, Casey and James were able to get under the hood of a pretty closed off industry, which they’ll break down for us today.

The explosion of AI use comes with many impacts, societal, economic, public health, and so none of them are equally distributed in terms of harm. But today, we’re just focusing on the environmental cost. And speaking of cost, let’s open our first tab. How much energy does a query cost? Let’s start with a little AI 101. When we talk about the environmental impact and energy use, where is all of this computing actually taking place? MIT Technology Review’s James O’Donnell broke it down.

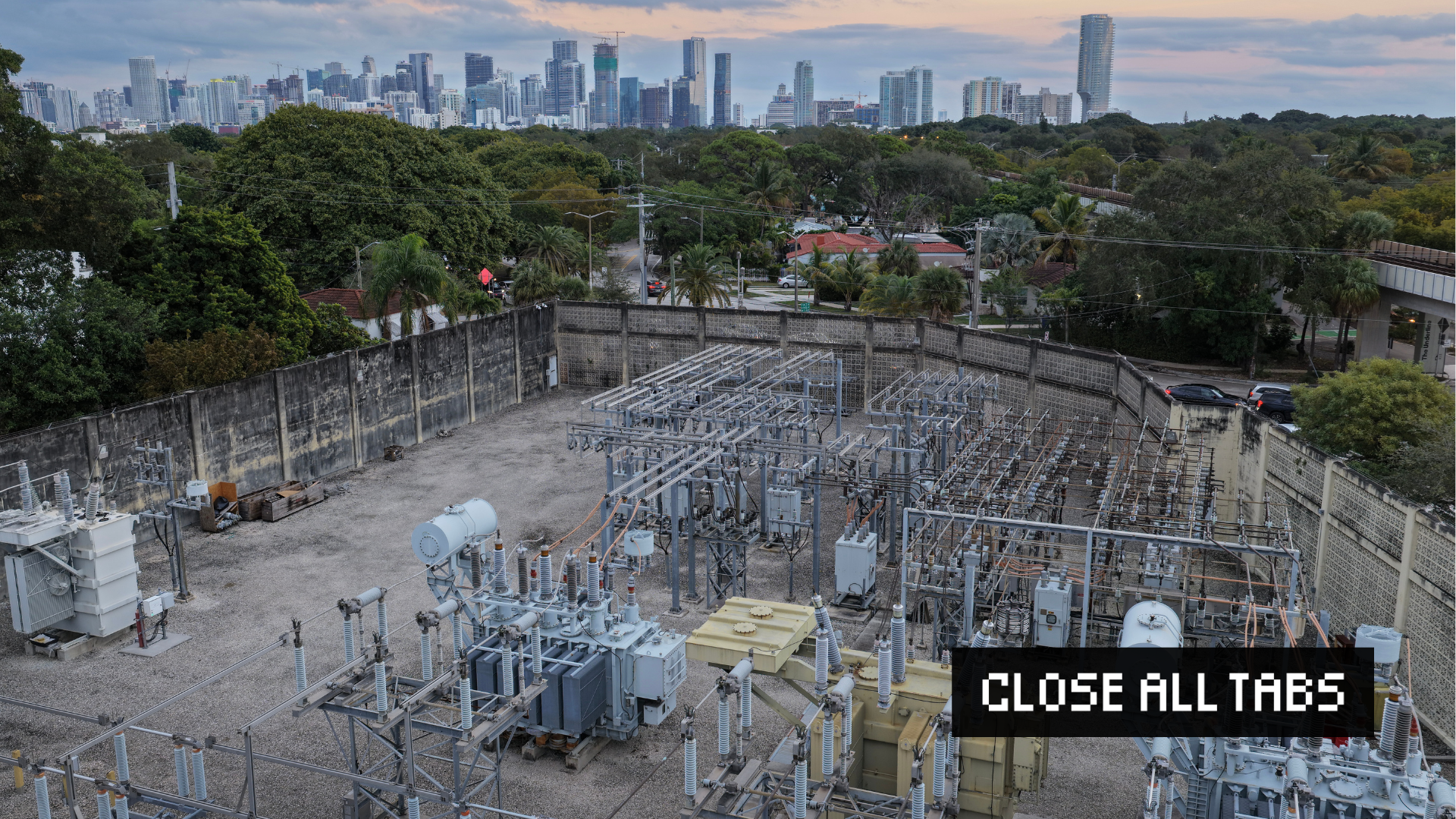

James O’Donnell, Guest: The computing is really taking place in buildings called data centers, which there’s about 3000 of them, uh, around the country. There’s even more as you go worldwide and really to visualize this, these are just like monolithic, huge, boring looking buildings that don’t have any windows or anything interesting on the outside and inside are just racks and racks of computers and chips and servers, crunching a lot of numbers.

Morgan Sung: What we call artificial intelligence has existed in some form since the 1950s. But the technology that we call AI today is very different. There are many types that we now lump together under the AI umbrella, which all have different energy requirements. But for this deep dive, when we say AI, we’re referring to generative AI, specifically, the models that produce content based on a human entering a prompt. They include large language models, or LLMs, like ChatGPT and Claude and Gemini. When it comes to generative AI models, there are typically two different processes involved: training and inference. These also factor into the total energy use.

James O’Donnell: So training is what you do when you want to build an AI model from scratch, from nothing and you, you have a large language model that is only going to be as smart as the data that you feed it. So training is basically the phase where you’re taking massive amounts of data. Normally this is a lot of language and text, which could be everything from the internet, could be every book that’s ever been written, uh, regardless of if these companies have the legal right to access that data, but they’re putting a bunch of data into this AI model. And the AI model is basically learning how to create better and better guesses of the text that it outputs. So it’s learning to generate texts, to string words together, to string sentences together and paragraphs together that sound realistic and accurate. And it’s doing that by noticing patterns of what words go together in this large data set.

So training is sort of the number crunching of feeding all of that data into an AI model and at the end, it spits out this model that has learned millions and millions of parameters, we call them, basically like knobs on an AI model that help the model understand the connections between different words. And at the end, you have this model that can generate text.

A lot of electricity is used in the process of training that AI model. Years ago, that was like, when I say years ago, maybe two or three years ago that was the main concern of how much energy AI was using was really in that training phase. And what Casey and I discovered in our reporting is that that has changed really significantly. So most AI companies today are, you know, they’re planning for their energy budgets to be spent more on inference.

Morgan Sung: So, what is inference?

James O’Donnell: Inference is every time you ask an AI model something, so every time you ask a question or have it generate an image or a video, anytime it actually does the thing of generating something that’s called inference. And so the individual amounts of energy that are used at the time of inference can be quite small or, or sort of big. Um, but it’s really the summation of all of that, that gives you kind of the energy footprint of a given AI model.

Morgan Sung: The generated output also changes the energy usage. The more complicated the prompt, the more energy it uses.

Casey Crownhart: So, in our reporting we looked at text, images, and video. So kind of really broadly, and again, it can still vary, even within kind of a text query, depending on how complicated your ask is. So are you asking something to rewrite the whole works of Shakespeare, but like, in pirate speak, or are you just asking for a suggestion for a recipe? The open source models that we looked at, we found that the smallest models, if you were kind of asking a sort of standard query, might use about 114 joules of electricity. That’s equivalent to roughly a 10th of a second in a microwave, so a very, very small amount of electricity. A larger text model and one of the largest text models we looked at would use a lot more, so more like 6,700 joules, that’s about eight seconds in a microwave. So again, fairly small numbers.

Morgan Sung: Also, the bigger the model, the more energy it uses. AI models have parameters. Like James said earlier, these are basically the adjustable knobs that allow models to make a prediction. With more parameters, AI models are more likely to generate a better response and are better equipped to handle complex requests. So, asking a chat bot, “What year did Shakespeare write Hamlet?” Is generally a less complex request than, say, “Translate all of Hamlet into pirate speak.” The smallest model that Casey and James tested had eight billion parameters. The largest had 405 billion parameters. OpenAI is pretty hush-hush about their infrastructure, but some estimate that the company’s latest model, GPT-5, is somewhere up in the trillions. So, as models get bigger, they need to run on more chips, which needs more energy.

Casey Crownhart: What was really surprising and what I think really stood out in our reporting was that videos, based on the models that we were looking at, used significantly more energy, so thousands of times more energy than some of the smallest text models. So one model that we looked at used about 3.4 million joules of energy. That’s about an hour of microwave time. So there’s a really wide range here.

Morgan Sung: Here’s another factor: reasoning models. Investors are all over these right now. Reasoning models are marketed as literal thinking machines that are able to break down complex problems into logical steps instead of just predicting the next answer based on the patterns it recognizes. They’re advertised to think like a human would and supposedly will become more energy efficient the smarter the model gets. One of the researchers that Casey and James worked with at Hugging Tree put this to the test.

James O’Donnell: You know, a lot of people are excited about this idea of reasoning models. And so when this researcher studied these and figured out whether or not they’re energy efficient, she found that a lot these reasoning models can actually use 30 times more energy than a non-reasoning model.

Morgan Sung: And then there’s the water usage. AI datacenters use massive quantities of water.

Casey Crownhart: Yeah, this is something that has been a conversation and there’s still I think, to some extent, a lot of uncertainty about. But basically, data centers use water directly for a lot cooling systems. A lot of data centers are cooled with what’s called evaporative cooling. So, you know, water evaporates to cool down the equipment. There’s also sort of indirect water use, which is a little trickier to calculate, but there’s also water that’s used in power plants. And so if you kind of think, okay, the power plant is needed to power the data center. So the water used in the power plant, you can kind of attribute to AI as well. Oftentimes the water that is required in a data center has to be very, very high quality, very pure water because you’re dealing with very sensitive equipment. And so there is this big conversation about water. Google released estimates about its water use per query as well, but kind of to sum it up, there is a pretty major water requirement and we’re starting to see that as, again, data centers are being built in places, including those that are very water stressed.

Morgan Sung: So that’s what we do know about AI and energy consumption. This is the usage that can be measured, even if companies aren’t the most upfront about their numbers. But what about everything else? We’re opening a new tab, after this break. Welcome back, we’re opening a new tab. What AI energy use isn’t being measured? So we’ve talked about the front and most visible uses, energy usages, generating videos, generating lists, translating Shakespeare’s text into pirate speak, right. What’s happening in the background that’s also using up energy? Like, how many times do you have to run a microwave for those processes?

James O’Donnell: Well, I think it’s hard to know. Like since we’ve done this reporting, AI is being put into many parts of our online life and we don’t always have a lot of choice or visibility into how AI is being using used. So for example, Google famously, uh, went from just presenting you search results to then summarizing those search results with AI overviews. So now for the most part, people aren’t looking very far down that search page, they’re actually just relying on the AI overview. We would love to know how much energy is used by Google every time it creates an AI overview and the percentage of those searches that it uses overviews for, we weren’t able to get that information. Uh, Google wouldn’t share it with us. And so, you know, AI is being put into all these different parts of our online life. And I think we’ll look back on this as the sort of like simplest calculation of, of being able to estimate, you now, how much is used when you try and make a recipe or generate an image or something. But the truth is, as you point out, AI is sort of being put into everything and it’s going to be harder and harder to sort of track the footprint as that goes on.

Morgan Sung: Can you elaborate on why this topic appears to be so divisive and so confusing for so many people having to confront their energy usage through AI?

James O’Donnell: Okay. I have thoughts, but I’m sure Casey does too. So, you know, it’s not like asking ChatGPT a question is like, you know, polluting the earth as much as driving a 3000 mile road trip, right? Like ,we’re talking about small, relatively small numbers here, but it gets a lot of attention, I think, because public opinion for AI right now is just so abysmally low because so many people are skeptical of whether or not it’s really benefiting all of us. And I think the energy footprint is just kind of this glaring issue for people that say, like, what are we getting out of this technology, especially if it’s sort of draining us of resources.

Casey Crownhart: I think part of the interesting phenomenon is that AI has really like crashed onto the scene for the general public. It’s this whole kind of new thing that we’re all having to kind of reckon with, like what is this doing to our brains? What is this going to our grids? It’s I think it’s natural to question this like entirely new thing. Another thing that I think is really interesting is that, as James mentioned, this is becoming less so, but to this point, it’s kind of discreet and countable in a way that a lot of our other activity, especially online activity, isn’t. You can go out on and, you know, how many times am I messaging this thing? So I think that kind of has lended itself to the natural kind of like, well, how much does each one of these queries, what does that mean for energy?

Morgan Sung: So Google recently released data on the energy footprint of its AI model, Gemini, a couple of months after you guys put out your report. What did you make of that? Like, was it helpful? Can we trust those numbers? I guess wouldn’t they be incentivized to portray themselves as very energy friendly?

Casey Crownhart: Yeah, it would have been nice to get these when we were reporting, but as James mentioned earlier, these companies know better than anybody what their energy footprint is. So I think there’s such value in getting some of this data. And Google had a really good technical report that went through kind of in-depth, you know, here’s where the energy is coming from this much from, you know the AI chips, this much from other processes. But I think it’s really significant what wasn’t included in that report. And what wasn’t included in the report is any sort of information about, you know, the total queries that its Gemini model gets in a day.

So Google is able to point to this number and say, hey, look, this is such a small number. It’s in line with what we found for, kind of, our median text model. You know, something like a second or so in the microwave per query. But that’s, you know, for what Google says is an average or median query. You know, it’s not kind of giving us the full range, including, you now, different kind of queries that we know would take up a lot more energy. It doesn’t include image and video, which we know are more energy intensive. And ultimately we’re not able to, without that total number of, you not, how many times is this model being queried and giving responses a day? How many users, how many daily users? We don’t know the total footprint. We can only say, here’s this little number.

Morgan Sung: Let’s talk about the energy grid. The type of energy matters, right? Like there are a lot of discussion on renewables versus fossil fuels. What might impact where that energy comes from when it comes to building data centers and maintaining them?

Casey Crownhart: This is something that I really focused on in our reporting because as I think I put it in the piece, if we just had data centers that were hooked up to a bunch of solar panels and they ran when the sun is shining, oh, what a lovely world it would be, and I would be a lot less worried about all this. But the reality is that today, grids around the world are largely reliant on fossil fuels. So burning things like, you know, natural gas and coal to run the grid, keep the lights on. And one concern is what the grid will look like as energy demand from AI continues to rise.

So today, we see that data centers are really concentrated on the East Coast, in places like Virginia, tends to be very natural gas heavy, reliant on coal. There are data centers that are on grids that have a lot more solar and hydropower and wind, and that means that the relative climate impact of data centers in those places can be lower than in the more fossil fuel-heavy places.

But I think there’s a concern that as a lot, a lot of data center come online really quickly and need more electricity added to the grid in order to run, what is being added to grid in in order support those? Right now, the overwhelming answer is natural gas. And so that means that a lot of these new data centers will come with a pretty significant climate footprint attached.

Morgan Sung: We may not know the exact amount of energy that the AI industry is actually using, but what we do know is that it’s a lot, and it is putting a strain on our already limited resources. Each individual query does cost something, and it adds up. Plus, there’s everything running in the background that we can’t measure. So what is each individual person responsible for? I mean, should we be worried about the future? Is there anything that we could actually do? Time for a new tab: does my AI footprint matter in the big picture? Luckily, Casey dove into this exact topic last year. She believes that policing individual AI usage isn’t as helpful in the grand scheme of things. Here’s why we should shift our focus, instead of putting the onus on each person to change their own behavior.

Casey Crownhart: As we went through this reporting, I got a lot of questions and I had a lot of questions myself about, you know, what does this mean for me and my personal choices about AI? And again, kind of as somebody who spent a lot of time reporting on climate change, it really reminded me of the conversation around climate footprint. You know, what is my climate footprint? What should I personally do differently to help, kind of, address climate change? And what I’ve come to kind of understand through my reporting and believe is that climate change is this massive problem that goes beyond any single one of us. And there’s a really significant limit to how much our individual choices can address a global problem that is very systemic.

You can compost all you want, but if only gas vehicles are available to you and that’s the only way you can get around in your community, there’s only so much you can do. And we now know that some fossil fuel funded PR campaigns helped to popularize this idea of carbon footprint to kind of shift the focus on to individuals and away from these big, powerful companies.

And I think that I see some parallels with AI today, you know, this attempt to kind of shift focus on, you now, well, are you using ChatGPT too many times in a day rather than what is the global impact and like, why aren’t these companies being more transparent about what the energy use of AI is on their scale.

So I think ultimately, you know, there are limits to this. Like if you’re making a million AI slop videos every single day, I think that’s an individual action that you could probably safely make a choice that would be better for energy use. But overall, I think we should more be using our limited time and energy in the day to push for more transparency. You know, ask for regulations around AI and what’s powering it, and just generally not be so hard on ourselves because we operate in this system where it’s increasingly hard to get away from AI. As we’ve talked about, even if you don’t choose to go onto, you know chatgpt.com, you’re often, you’re part of this AI ecosystem. So we need to be talking about what that overall system looks like and how we can change it rather than the limited power of individuals.

James O’Donnell: One of the biggest unanswered questions every time a data center is open is actually like, what’s the energy source going into that? And is it going to be, you know, powered with renewable sources or not? Is it just going to run 24 seven on natural gas? And so sometimes if you hyper focus on this question of your own individual footprint, it can kind of make you forget that actually there are decisions still to be made every time the data center goes up that will arguably have a bigger impact on the sort of net footprint, net emissions of it all.

Morgan Sung: What do we know about where the AI industry wants to take us in the future, near future, like three years from now? What do they need energy-wise or water-wise to get us there?

James O’Donnell: AI companies are planning for some pretty, uh, unprecedented levels of investment in, in data centers and, you know, to power all of those unprecedented levels of investment in power plants and nuclear energy and things like that. Um, I think where they want to go, uh, is to build AI models that are bigger first of all. To do that you need more and more chips and more and more power, and so there’s an incentive to just amass all of this energy and electricity.

And then on the product side of it, I think these AI companies imagine that the world of AI in five years will not just be large language models that people type to and get an answer back, but that image generation and video generation and real time voice chats are kind of a part of our everyday lives. And so they’re planning for a lot more demand as well.

And so you could think of this project from OpenAI and others called Stargate, which is basically a half a trillion dollars of investment into data centers that they want to pop up around the country. And I think the reason why they’re seeing success politically from this is that AI companies have framed AI as a question of national security, right? If the US wants to win this AI race against China, then the country that has the most energy is the country will create the best AI and the sort of you know, impedance to all of that is access to, to energy. And that’s why these companies have sort of made it their top priority.

Casey Crownhart: Yeah, and just to add to that, I mean, I think these big dreams about, you know, how big AI could get, it’s going to be a lot of electricity. So as of 2024, data centers used over 400 terawatt hours of electricity, about 1.5% of all electricity used around the world. By 2030, the International Energy Agency says that that could more than double reaching 945 terawatts. Sorry to use inscrutable units, but that’s about 3% of global electricity consumption.

Morgan Sung: What is that in microwave hours? [Laughter]

Casey Crownhart: A whole lot of microwaves, so many microwaves. So I think that basically we’re seeing really significant, really fast shifts and fast growth in electricity, including in places like the US that have seen very flat electricity demand for over a decade. And so I think that this is all going to add up to really complicated effects and really complicated, kind of, effects for local communities where these data centers and where these power plants are gonna be used.

James O’Donnell: Yeah, this is something I didn’t totally get before I learned more from Casey and before we started reporting on this. So data centers were doing a lot of stuff in the early 2000s, like, this is Netflix, social media, like, all sorts of streaming, but electricity going to those data centers stayed pretty flat, and it wasn’t until AI that you actually started to see a huge jump in the amount of electricity that data centers required.

Morgan Sung: Most AI companies, or AI hype guys who are investing very heavily in AI companies will say something like, oh, AI can solve problems like climate change, so the energy usage is worth it. How much do you guys buy into that argument? Llike, does it hold any water?

Casey Crownhart: There’s so much potential for all kinds of AI, again, beyond chatbots, in all kinds problems that are related to climate change, from materials discovery, finding new materials that could make better batteries or help us capture carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere, superconductors that can move electricity around super efficiently. There’s also ways that AI could be used to help the grid run more efficiently.

There’s really interesting research in all of these areas that I’m following very closely. But at this point, it’s all early stage. It’s all research. And I think there’s great potential for AI to be a positive force for the climate. But I think it’s absolutely irresponsible for us to punt on all of this concerns about AI’s current energy use because of some potential. Because there’s always the chance that this doesn’t work.

And I think in any case, the progress could be significant, but it’s not gonna be a silver bullet. So I think we need to reckon very seriously with the current energy problems that we’re seeing now, rather than try to make some future promise that may never come true, build all this infrastructure that will be online for decades to come and could change our climate forever. Just doesn’t make sense.

Morgan Sung: What do you think the most misunderstood part of this whole energy AI use conversation is?

Casey Crownhart: I think that there’s kind of a nuanced picture of just how important AI energy use is in context. So it is true that AI is probably a small part of your individual energy picture. And in fact, in terms of like the global energy use picture, it’s 3% in 2030. That doesn’t seem like very much. But that kind of change over such a short amount of time is going to be very significant for especially local grids where this is taking place. It will have significant impacts for climate change.

This kind of build out will definitely not go unnoticed by the climate, but I think the biggest impacts here will be faced by local communities seeing data centers going up, local communities with new fossil fuel infrastructure going up. And so all at once, this is a small fraction of individual and even global energy use, and a very, very significant trend for the energy system of the world.

Morgan Sung: Looking toward the future is important, but the AI industry is changing residential communities right now in real time. The data center room promises to bring jobs and economic growth, but are AI companies following through on that?

Next week, we’re taking our deep dive to one of the fastest growing hubs for AI data centers, Atlanta. But for now, let’s close all of these tabs.

Close All Tabs is a production of KQED Studios and is reported and hosted by me, Morgan Sung.

This episode was edited by Chris Hambrick and produced by Chris Egusa, who’s our senior editor and also composed our theme song and credits music. Additional music by APM. Close All Tabs producer is Maya Cueva. Brendan Willard is our audio engineer. Audience engagement support from Maha Sanad. Jen Chien is KQED’s director of podcasts. Katie Sprenger is our podcast operations manager and Ethan Toven-Lindsey is our Editor-in-Chief.

Some members of the KQED podcast team are represented by the Screen Actors Guild, American Federation of Television and Radio Artists, San Francisco, Northern California local.

This episode’s keyboard sounds were submitted by my dad, Casey Sung, and recorded on his white and blue Apple Maker Ala F99 keyboard with Greywood V3 switches and Cherry Profile PBT keycaps.

Okay, and I know it’s a podcast cliche, but… if you like these deep dives and want us to keep making more, it would really help us out if you could rate and review us on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you listen to the show.

Don’t forget to drop a comment and tell your friends too, or even your enemies, or frenemies. And if you really like Close All Tabs and want to support public media, go to donate.kqed.org/podcasts.

Thanks for listening.