Episode Transcript

This is a computer-generated transcript. While our team has reviewed it, there may be errors.

Morgan Sung, Host: Here on Close All Tabs, we cover all different sides of tech and the internet — the good, the bad, and the gray areas in between. Today, we’re doing something different, and taking our deep dive abroad.

The tech industry is increasingly intertwined with global conflict. Like how Silicon Valley’s AI obsession has fueled the automated warfare in Israel’s attacks on Gaza, or US bomb strikes in Iraq and Syria. So-called “defense tech” startups are attracting billions in funding. And like we’ve talked about on this show before, the Pentagon’s Cold War investments actually built Silicon Valley. This startup approach to weaponry has some pretty concerning implications for the future of war. And we’ve seen, in real time, the way these advancements in surveillance and automated warfare are being used to oppress people — like Palestinians in Gaza.

At the same time in another region plagued by conflict, Ukraine, tech culture has become a vital part of the country’s resistance against Russian aggression.

That’s the kind of story that Erica Hellerstein stumbled upon, as she prepared for her own trip to Ukraine. Erica is a Bay Area investigative journalist who reports on human rights, politics, and tech. Back in June, she spent three weeks around Kyiv on a reporting trip, working on a project about her own family’s roots in the country.

Just before her trip, she heard a story about a Ukrainian engineer who had worked for a Bay Area tech company, but left his job to join his country’s defense forces. It got her thinking about the connection between Silicon Valley and the Ukrainian fight against Russian occupation. She started digging and according to the people she talked to, the tech sector is part of the reason Ukraine is still standing today.

These are the Geeks of War — that’s what one Ukrainian drone operator nicknamed the group. Ukraine actually has a long history of technological innovation that is still alive today, and is fueling the country’s resistance through an army of engineers, coders, hackers, and tinkerers.

In this special episode, Erica will introduce us to a few of these “Geeks” and we’ll explore how this new generation is blurring the lines between the digital and physical battlefield — reshaping the next generation of conflict, and maybe even the future of war itself. I’ll let Erica take it from here.

Erica Hellerstein, Reporter: It’s around 11:55 pm when the first alarm goes off.

[Alarm sounding from Air Alert app]

Erica Hellerstein: The noise shatters any illusion I had that my first night in Kyiv would be quiet or peaceful. I’ve been doomscrolling on my phone in a bomb shelter connected to my hotel in Kyiv. It’s surprisingly nice, with wifi, beverages, even bean bag chairs. On heavy nights of bombardment, like tonight, these sirens can go off multiple times and last for hours.

But most of the time I’m in Ukraine, I’m hearing these alarms digitally through an app on my phone called Air Alert. The Ukrainian government developed the app towards the beginning of the war, and it’s now been downloaded at least 27 million times. That’s in a country of 39 million people.

Air Alert sounds a loud, jarring alarm whenever a Russian missile strike, or drone attack is detected in your region. And the voice telling you to find the nearest shelter? None other than Jedi master Luke Skywalker.

[Mark Hammill from Air Alert app]

Attention. Air raid alert. Proceed to the nearest shelter.

Erica Hellerstein: Or rather, Mark Hamill, the actor who played the beloved character in Star Wars. Hamill’s a vocal supporter of Ukraine so he pitched in to voice the English language version of the app.

[Mark Hammill from Air Alert app]

Don’t be careless. Your overconfidence is your weakness.

Erica Hellerstein: I’ve learned, though, that the app only gives you basic information. To get details, I go to a different app, Telegram, where I follow a volunteer-run channel that gives updates about what kinds of missiles, or drones, are in the air.

As if two apps aren’t enough, I’m also on WhatsApp messaging a group of journalists who are also in Kyiv. Some are in the same hotel shelter, others are sheltering in the hallways of their apartment buildings or metro stations. Everyone is sharing updates. “Drone flew right over our roof,” someone writes around 1 am. Another, two minutes later: “Loud explosion not far from my place.”

Finally, around 6am, another alert goes off. Once again, I hear a familiar voice.

[Mark Hammill from Air Alert app]

Attention. The air alert is over. May the Force be with you.

Erica Hellerstein: That means, at least for now, the skies in Kyiv are safe. But as dawn breaks, the scale of the destruction starts to come into focus. About two miles from where I’m staying, an apartment building was hit by a ballistic missile and reduced to rubble – there are reports of people still trapped inside. A Kyiv metro station and university were also hit. All told, ten people, including a child, were killed in the onslaught.

This has become a regular occurrence in Ukraine. People have been living through these kinds of attacks for years. Unable to sleep through the wails of the sirens, reading news about buildings blown up, civilians killed and then somehow, still managing to go about their daily lives – going to work, picking up their kids, celebrating birthday parties, getting married.

And beyond the apps like Air Alert, technology has become a centerpiece in this war — hacking software, killer drones, medical robots delivering supplies to the frontlines. It’s transforming how people experience war. Now, every aspect of our lives, including conflict, is mediated by our digital world.

But the people behind the screens can be a little mysterious. I wanted to learn more about them. To understand the workers and whizzes changing what warfare looks like, with major implications for the rest of the world. I wanted to meet the self-styled “Geeks of War.”

And for that, we’ll need to open a new tab: [Typing sounds] Meet the Geeks

Erica Hellerstein: My first guide to the geeks is a couple I met in Lviv, which is a Western city in Ukraine. Dimko and Iryna Zhluktenko. They’re the co-founders of Dzyga’s Paw. It’s a Ukrainian nonprofit that donates defense technology to the frontlines. Both Iryna and Dimko used to work in tech. Dimko was a software engineer, Iryna a product analyst for the San Francisco-based tech company, JustAnswer. But after Russia invaded Ukraine, they quit their jobs and threw themselves into Dzyga’s Paw, which, by the way, is named after their adorable little fox-faced pup, Dzyga.

I stop by the organization’s headquarters one night. They greet me with a tour of the space.

Iryna Zhluktenko: You can just come like this. So we used to live here, so this is actually, like a normal house location, but very old one is from 1906, so it’s more than 100 years old, and here you have our main working, like a little open space.

Erica Hellerstein: There’s a small party happening, with some women playing an intimidating-looking card game in the kitchen.

Iryna Zhluktenko: The girls are playing [inaudible] Do you know this game? No, you should try.

Erica Hellerstein in tape: Okay, I’m horrible at cards.

Erica Hellerstein: We pass an entire wall full of framed thank you letters from different military units. There’s another wall, too, full of patches from soldiers and volunteer fighters, some coming from the other side of the world.

Erica Hellerstein in tape: Wow, I see Argentina. That’s far.

Iryna Zhluktenko: That’s from, yeah, from international volunteer who’s fighting here in Ukraine, from Argentina. This is a Estonian one from Estonian cyber defense forces.

Erica Hellerstein: Iryna shows me another decoration tacked to the wall: A downed Russian drone. And it’s in really good shape. So she decides to give it a whirl.

Iryna Zhluktenko: Let me try to do it. So it turns on. And if I had a controller, if I had a like TX controller, I could launch it and start it, probably.

Erica Hellerstein in tape: So this is like a war treasure?

Iryna Zhluktenko: Looted from Russians. Yes.

Erica Hellerstein: Once I tear myself away from the shiny objects, I sit down with Dimko, Iryna, and of course, Dzyga, who has extreme zoomies.

Iryna Zhluktenko: She is the boss of the operation. [Laughs]

[Dzyga barks]

Erica Hellerstein: They tell me that the project came about in the early months of the war. Of course, like so many other Ukrainians, they wanted to help. And they started to think about what they could bring to the table. And that’s when Dimko and Iryna, had their a-ha moment. “We’re nerds!”

Dimko Zhluktenko We’ve decided that well, we might just use our, uh, tech experience, our tech geekiness, uh, to, uh, innovate. Some of the approaches on the battlefield.

Iryna Zhluktenko: We figured out, okay, we can help better when our expertise is. So basically we started looking more into more advanced equipment. We started looking into drone and things like that and because we had friends in the military, uh, it was like our first point of contact because like we had people we could trust. And we started, you know, buying and supplying some tech devices.

Erica Hellerstein: They started with what their friends in the military really needed: equipment. Drones, Starlink units — which provide remote internet access – long-range encrypted radios, thermal cameras. Dzyga’s paw has since grown from a scrappy idea into a multi-million dollar nonprofit. In October alone, they delivered over $230,000 worth of equipment to the military, according to the organization.

And all of this high tech gear goes to soldiers and drone operators who are stationed near the frontlines.

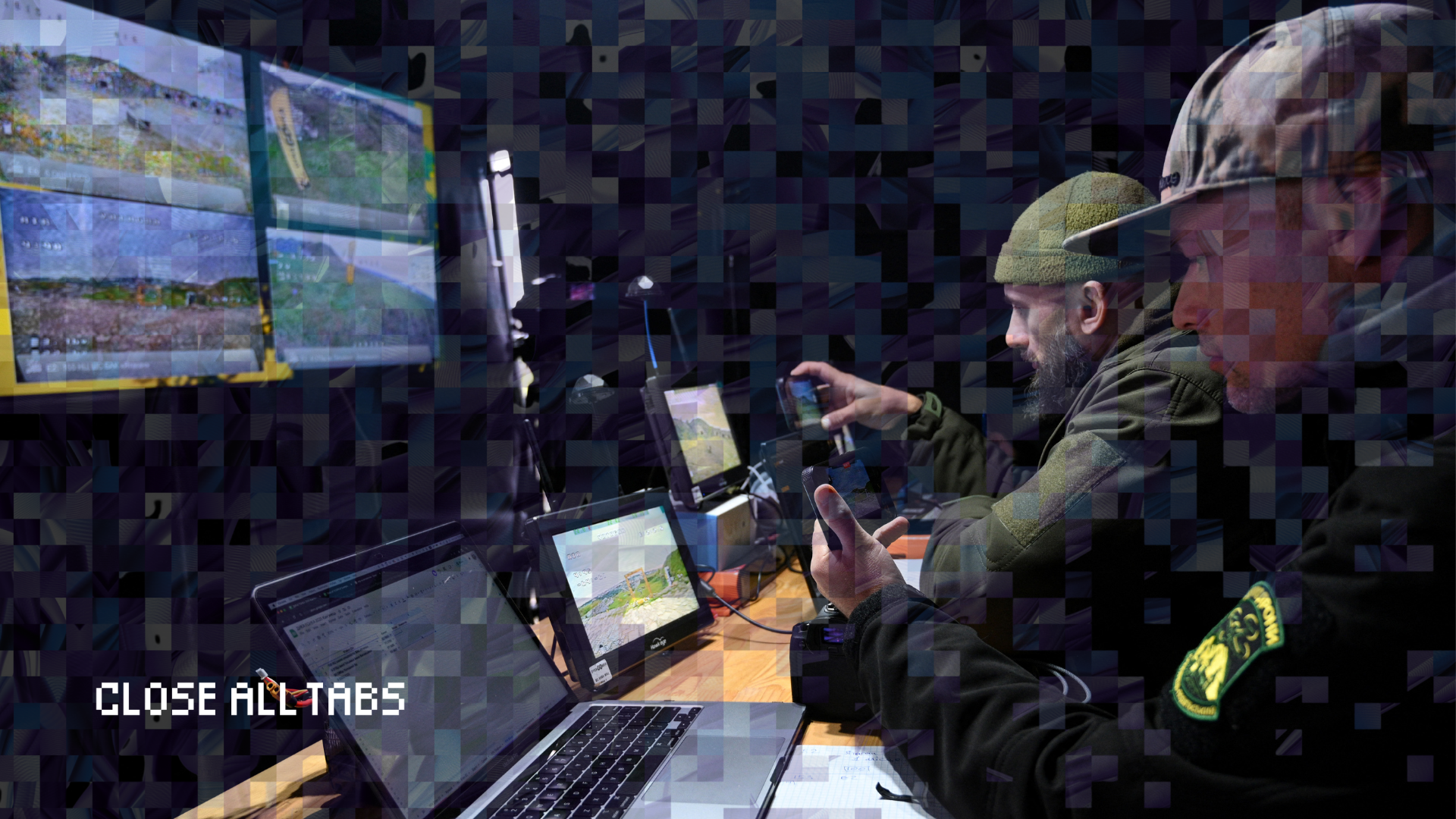

They often work in hideouts, or command centers, miles from the front, flying drones by remote control while wearing a headset that shows exactly what the device sees through its camera. Other soldiers sit beside them, watching live maps on screens, calling out targets and coordinates in real time.

Dimko explains what these command centers look like in action.

Dimko Zhluktenko: Basically an underground shelter with, uh, tons of, uh, big ass four screen TVs or something. Uh, and guys looking like they just finished the MIT or something.

So literally geeks of the war, sitting in those command centers and analyzing what is happening at the battlefield, and then suggesting what decisions should be taken to be the most effective.

Erica Hellerstein: About a year ago, Dimko also enlisted as a drone operator for a Ukrainian military unit.

Dimko Zhluktenko: Because this is my chance to, uh, well defend my home, defend my family, and, uh, in the end defend my country.

Basically the job is to do the reconnaissance. Um, you have this big UAV that, uh, like a fixed wing kind of a thing that you launch in the air.

Erica Hellerstein: Drone warfare has quickly become one of the defining characteristics of this conflict. The kind Dimko pilots are called UAVs — or unmanned aerial vehicles. They look like small airplanes, and like Dimko said, they’re mainly used for reconnaissance.

Dimko Zhluktenko: It has the radio connection, so you have the radio signal link, uh, to it. And, uh, you have the live stream from that, you stream that footage into one of the IT systems that we have, uh, in the armed forces.

Erica Hellerstein in tape: Okay

Dimko Zhluktenko: So all of the people interested in the situation in the area. Can watch that live stream.

Erica Hellerstein: Then there’s this other kind of drone, called an FPV. That stands for first-person-view. They’re some of the most common drones on the battlefield right now. Once upon a time, these drones were mainly the toys of hobbyists and creatives. You know that insufferable wedding reel you saw on Instagram? Probably shot on an FPV drone.

When Russia invaded, the Ukrainian military started rolling them out on a massive scale. They cost next to nothing. They’re endlessly scalable, and for a country like Ukraine, with far fewer resources and manpower than Russia, they’ve been a game-changer. Drones that can be bought for just a few hundred dollars are now taking out Russian tanks and artillery worth millions.

There are swarms of these things buzzing around now on the front, some with cameras for spying, others loaded with explosives to detonate on their targets. And they’re responsible for massive damage. Drones now account for as much as seventy percent of casualties on both sides, according to Ukrainian officials.

Experts are already warning that this rapid, wide-scale shift could dramatically change the future of conflict. Other countries are likely to learn from or maybe adopt the technologies and tactics deployed in this war. And It’s not just militaries that can repurpose these technologies. Paramilitaries, militias, and extremist groups can all easily purchase and deploy drone technology.

As drone warfare becomes more lethal on the battlefield, Dimko tells me that his work is also getting more treacherous as the war progresses.

Dimko Zhluktenko: It is very and very dangerous because the kill zone is getting wider and wider because of the danger of FPV drones there in our direction.

We have a lot of, uh, Russian groups there, specifically hunting pilots like us.

Erica Hellerstein: But even though Dimko is now an official member of the Ukrainian military, the organization he helps run, Dzyga’s Paw, started completely outside of that system as a grassroots, volunteer mission. And now it’s directly helping units like his and this is really common.

Ukraine is heavily dependent on volunteers. People like the Dzyga’s Paw team, delivering supplies to the frontlines, volunteer air defense groups that shoot down Russian drones in the middle of the night, or Ukrainian tech companies building safety apps for civilians. All of this experimentation, this volunteer work – it’s been a really important part of Ukraine’s survival.

Iryna Zhluktenko: In a classic battlefield, it’d fail. But, um, it’s a constant competition of technology again and I still feel we are more rapid. We are more fast in terms of inventing something new. I wanna believe at least that, um, it all comes from our initial desire to survive and to fight for our country ’cause uh, there were many different people with different careers and professions, but, uh, huge part of them switched to thinking in this direction.

Erica Hellerstein: And this bottom-up, grassroots approach represents a fundamental difference between how Ukraine and Russia operate.

Iryna Zhluktenko: Compared to Russia, it’s like they don’t have a, they like, everything is very like, top down. It’s controlled from the,yeah, from the state. So, indeed they have great engineers, but they are given like a task to develop something, to come up with a solution. While in Ukraine, it’s more of a like, grassroots thing and sometimes something brilliant just comes out of nowhere.

Erica Hellerstein: So how did Ukraine get here to this nimble and adaptive space for innovation and experimentation? And why does it all remind me so much of the tech culture in the Bay Area? We’ll get into that after this break.

Ok, we’re back. Time to open a new tab: [Typing sounds] Ukraine’s culture of tech innovation.

To help us understand Ukraine’s tech culture, we’re taking a visit to MacPaw — one of the most successful tech companies to come out of Ukraine before the war. They created the CleanMyMac software. I’m at the company’s headquarters in Kyiv.

This building was actually hit by a Russian missile back in December. There are still some traces of the attack around the building: Window glass damaged, parts of the exterior crumbling. Here’s MacPaw CEO Oleksandr Kosovan describing that day:

Oleksandr Kosovan: The rockets were very powerful so they destroyed all the facade of the building. All the windows were shattered. A lot of damage inside the office, but nothing super critical. We were very lucky in that none of our employees were injured. It was scary.

Erica Hellerstein: MacPaw has built several digital tools to support Ukraine during the war, including an app to help Ukrainian companies check on employees after attacks, software that helps computers identify Russian malware, and a special VPN to help people in occupied territories circumvent Russian censorship.

While getting a tour of the MacPaw office, something catches my eye. It’s a wall filled with a collection of old Apple products from across the ages. It’s got ancient looking grey computers, and those bulky, colorful desktops that always felt to me like the computer version of a jolly rancher.

Erica Hellerstein in tape: I remember having these in school. It brings me back. Very nostalgic.

Erica Hellerstein: Oleksandr created this wall as an homage to Apple, which has always been an inspiration to him. Before the war, he wanted to create a museum full of the company’s products. For now, this wall is a little shrine in the middle of the MacPaw office.

As a Bay Area resident, it’s kind of funny, being here and seeing traces of where I’m from all over the tech industry here. Granted, Silicon Valley is hugely influential but what surprises me is just how intertwined Silicon Valley and Ukraine’s tech industries are. Like how Iryna of Dzyga’s Paw worked for a San Francisco startup.

And this is not unusual I’m learning. For years, tech companies from San Francisco to San Jose have relied on Ukrainian engineers for their technical skills, English fluency, and lower labor costs. Companies like Google, Grammarly (which was founded by Ukrainians), Ring, JetBridge, and Caspio all had employees based in Ukraine when Russia began its full-scale invasion.

There’s a general cultural ethos here that feels familiar to my Bay Area sensibilities, like the food trucks, ping pong tables, and hoodies I see all over tech campuses in Kyiv. There was one friendship bracelet-wearing tech worker I talk to who tells me all about her recent ayahuasca healing journey in South America. I felt like I was back at home.

And then there are all the personal connections I notice with the Ukrainians I meet. Some worked for Bay Area companies. Or, have friends who live there for work. And since the war began, these transnational ties have become a quiet but meaningful network of support for Ukraine. The Silicon Valley–based nonprofit Nova Ukraine, which was co-founded by a former Facebook and Google employee from Kharkiv, has raised over $160 million in humanitarian aid.

Iryna’s old employer, JustAnswer, has expanded its Ukrainian workforce. It funded a pediatric mental health center in the country as well. Caspio helped relocate dozens of Ukrainian staffers safely out of the country, and continues supporting staff remotely. Sometimes, company Zoom calls will be interrupted by the wail of a siren telling Ukrainian workers to go to a bomb shelter.

While there’s a lot of overlap between these two parts of the world, the innovation mindset that runs through Ukraine’s tech sector has deep roots. It started long before Steve Jobs or Silicon Valley exploded onto the global scene, like, decades before.

In 1951, when Ukraine was still part of the USSR, engineers on the outskirts of Kyiv developed the first computer in all of Europe. They worked around the clock, under tough conditions, in a crumbling old building that was ravaged by bombing during WWII. The people who made this computer, they’re considered the godfathers of Ukrainian IT. Here’s Oleksandr again.

Oleksandr Kosovan: Most of the, uh [inaudible] or IT on that era was actually originated from Ukraine. And um, beside that, there were like so many engineers, like my father was an engineer. There are so, so many great engineers that were working for this industry back then. And, and this basically were like the birth of the modern IT industry in Ukraine. So when the USSR collapsed, this talent and this, uh, uh, knowledge, uh, stayed in, in Ukraine.

Erica Hellerstein: And today, the industry those engineers helped to create now plays a significant role in Ukraine’s economy. In 2024, Ukraine’s IT sector contributed 3.4% to Ukraine’s GDP, behind only the agricultural industry, according to a report published by the IT Association of Ukraine.

Oleksandr Kosovan: Literally hundreds of thousands of people joined, uh, Ukrainian army. They started to bring their experience and their, like, creative, uh, vision and approach, uh, to the Army. And they started to apply, uh, some changes from, from bottom up. Uh, because, uh, these generals here, they probably know how to, uh, find the war of previous era, uh, but they don’t, uh, definitely understand how they can apply these technologies in order to, to receive some, some advantage.

Erica Hellerstein: To this point, we’ve been mostly talking about the physical battlefield, like drones attacking targets in the real world. But a new frontline has emerged in this war — the internet. And the tools and tactics needed to fight in these spaces look completely different.

Let’s open a new tab. [Typing sounds] The new digital battlefield.

Our guide to this world is David Kirichenko, a fellow journalist who splits his time between the U.S. and Ukraine.

David Kirichenko: I’m a war journalist and since 2022, I’ve been working on the front lines, um, in Ukraine.

Erica Hellerstein: But he’s also been reporting on another front: the digital fight between the two countries. Because the information space between Russia and Ukraine has become its own proxy war, with each vying for support at home and abroad.

David Kirichenko: It certainly has, I think, a very big impact on what goes on the physical battlefield just from the amount of influence and impact that you can have.

Erica Hellerstein: Russia’s a country long known for its sophisticated cyber warfare campaigns. In the current conflict, it’s been deploying vast amounts of disinformation online to weaken support for Ukraine around the world — on social media, fake news sites, even video games. This practice, as David points out, has deep roots, going back to the Cold War.

David Kirichenko: Even since the 1980s, the Russians first started out by building like a newspaper in India. It prints a fake story and then you have a, a more slightly more credible one, print that, and then everyone just starts citing it and it circulates around the world. And an MIT study showed that, um, like the fake news it it spreads like six, seven times faster than the truth.

Erica Hellerstein: Enter: The Fellas. They’re a niche online community that has come together to fight Russian disinformation. They call themselves the North Atlantic Fellas Organization, or NAFO, for short. And because it’s the internet, their entire social media “army” has adopted the likeness of one very good boy: A Shiba Inu.

The members of this online battalion, who like to be called the Fellas, usually identify themselves on Twitter, or X, with a cartoon Shiba avatar. And they have one major purpose: To take up digital arms against Russian propaganda.

When a pro-Russian narrative pops up on social media, The Fellas leap into action. Their objective is to distract, mock and debunk the Kremlin’s talking points. Politico called the group “a sh*t posting, Twitter-trolling, dog-deploying social media army taking on Putin one meme at a time.”

There are now thousands of Fellas out there in the digital dog fight. They’re an organic phenomenon, borne out of internet culture. And they make anyone who earnestly tries to engage with their trolling look ridiculous. “Oh, you’re fighting with a cartoon Shiba at 3 pm on a Tuesday? Don’t you have anything better to do?”

David Kirichenko: The best way to counter Russia propaganda is by mocking it, ridiculing it, and showing that like, this is how ridiculous it is. And like you just make a joke at it yourself by sharing it. Just the fact that, you know, over the years you had all these high-ranking Russian and then other officials engaging with cartoon dogs on, on Twitter.

Erica Hellerstein: A less cheeky example of digital warfare is the IT Army of Ukraine. They’re a collective of volunteer hackers around the world who coordinate cyber attacks against Russia. They’ve attacked thousands of targets since the war began, from Russian banks to media outlets, and power grids. In June 2024, the group claimed responsibility for a large-scale cyberattack against Russia’s banking system, reportedly causing outages on banking websites, apps, and payment systems.

The IT Army of Ukraine isn’t a traditional military unit. It’s a sprawling, loosely organized network that runs primarily online. They post updates and send communications on their Telegram channel, where they have nearly 115,000 subscribers. They also have a website that lays out more information about their work and how to get involved. One page, for example, is titled: “Instructions for setting up attacks on the enemy country.”

David has also been reporting on this group. The IT Army’s spokesperson told him last year that its volunteer hackers had caused something like a billion dollars in damage from these attacks. David explains the anatomy of an attack.

David Kirichenko: You typically have people that you have the toolkit installed so it doesn’t interfere with your, your Netflix or slow down your internet. You couldn’t set it to, I want to run from like 12:00 AM to 6:00 PM, I’m gonna leave my computer on. So if the IT army, like, runs the botnet and wants to direct an attack, it has the access to the compute to be able to run it and send pings from a lot of different places to overwhelm, um, a system.

And so they like posted the, the toolkit onto their website so anyone’s able to go and, and download it. And it’s pretty, pretty simple to install it. And, uh, all you gotta do is just make sure that your computer is running and contributing your compute power to the botnet so that it’s overwhelming, like services when the attack begins.

I’ve met people that said like, even my 12-year-old child is like doing these, uh, cyber attacks against Russia. They just download the toolkit and, you know, you set, you can even set a timer, allow your computer to participate in this botnet

Erica Hellerstein: But these IT soldiers operate in a legally murky zone. There’s obviously something troubling about kids participating in cyberwar against another country. And, if someone participates in an attack from their couch on the other side of the world, are they breaking any laws?

David Kirichenko: It is a gray space. How do governments prepare to legislate for this. Like, are you a combatant If you’re engaging in like cyber warfare? Are you breaking any laws? Should governments build a cyber reserve or some sort of like legal framework for their, like, people to be able to participate in this stuff? I mean, it, you know what, if you’re in Poland and then you’re conducting some cyber attacks and the Russians are very upset and they can launch a missile and they claim that you’re an enemy combatant. And yeah, just it’s, it’s a very challenging space and for I think lawmakers.

Erica Hellerstein: For all the reasons he just laid out, most of the people I spoke with wouldn’t talk openly about participating in the IT Army. Though one person told me that “literally everyone with a laptop did.”

Regardless, all these IT Army volunteers are having a real impact, David says. And this theme of a decentralized, grassroots approach as part of Ukraine’s strategy — chaotic with flashes of ingenuity — it keeps coming up.

David Kirichenko: It ties back to Ukraine’s, wider story of, it’s a volunteer driven war effort. Like Ukrainian soldiers across the frontline are just dependent on online communities and, and volunteers. And so just people around the world have had such a big impact, both in information space, getting supplies to soldiers. Um, and one of the other ways has been on the cyber realm.

Erica Hellerstein: This grassroots system is pretty much the opposite of how Russia does things. Which is centralized, top down, structured. Just a few solutions, scaled across every single military unit. They’re two competing philosophies fueling this technological arms race between Russia and Ukraine. A war of who’s quicker to out-innovate the other side.

David Kirichenko: Ukraine is so decentralized, it’s kind of its biggest strength and biggest weaknesses. You have a zoo of solutions of every volunteer group. They’re making, they’re iterating, but then there’s so many different technologies and, and weapons, that everyone’s using different things and it’s hard to standardize, but then it also makes it very effective. But then the Russians learn what’s working and over time they can steer the, the whole war machine to focus on a, on a few things, and it’s sharing those lessons.

Erica Hellerstein: And no matter how things end, what they’re coming up with is changing what war looks like altogether. With major implications.

David Kirichenko: Drones dominate not just the, the frontline itself, but it’s changed like naval warfare. Ukrainians’ naval drones have helped to neutralize a third of Russia’s Black Sea fleet, and they’re basically blockading Russia’s fleet that had to retreat from occupied Crimea. Ukraine has built, right, these ground robots that are becoming like mechanical medics, and the naval drones help shoot down multiple Russian helicopters, a couple of fighter jets. And those two fighter jets that were lost in Mayra, um, each like 50 million. So you can have a sea drone worth like 200, $300,000 with the, uh, missile worth that much or less, shooting down something that’s $50 million.

And so we’re going to continue to see the proliferation of like, cheaper, faster tech. And we gotta learn what, you know, how do we prepare for that?

Erica Hellerstein: Technology is fundamentally a gray area. It’s built on these bursts of genius and promise, and also shows up in our modern world in dark and scary ways. It’s that first European computer, created out of the ashes of a bombed-out building in the Soviet Union. It’s Silicon Valley revolutionizing the world we now inhabit. For better, in some ways and in many ways, for worse: consolidating power, money, data, and influence, on an unimaginable scale.

And that’s the real story of the geeks of war. There are the lifesaving apps, like Air Alert, Telegram channels with real-time information about missiles and drones, VPNs connecting people in occupied territories to a bigger, broader, information ecosystem- Tools that are keeping people safe, connected and alive.

But there are also new technologies that are killing people, and the potentially catastrophic consequences of cyber saber-rattling. Destroyer drones, yes, they can give an underdog country like Ukraine an edge, but when you stop and think about their capabilities, the damage that can be unleashed with a tool literally anyone can buy for just a few hundred dollars, it’s terrifying. And then of course, there’s cyberwarfare, which can take down a whole country’s infrastructure, cripple power grids, communication networks, financial systems and thrust us all into completely uncharted geopolitical territory.

It reminds me of the early days of social media. When Google was still telling us not to be evil. When social networks were described as a revolutionary, democratizing force, helping to topple authoritarian regimes, organize mass protest, connect people all over the world. But we all know what actually happened was a lot more complicated than Big Tech’s aspirational mottos. The lens flipped. The narrative cracked. And now we’re living on the other side.

So what will be the story we tell about all these tools 10, 20 years from now? The technology we’re seeing in this war is opening up a new frontier. But who knows where it will be deployed next: What it will look like, who it will target. The geeks are showing us the future we just don’t know where it will lead.

Morgan Sung, Host: Thanks to Erica Hellerstein for her reporting and collaboration on this episode. Erica’s reporting was supported by a fellowship through the International Women’s Media Foundation’s Women on the Ground: Reporting from Ukraine’s Unseen Frontlines Initiative in partnership with the Howard G. Buffett Foundation.

With that, it’s time to close all these tabs.

Close All Tabs is a production of KQED Studios in San Francisco, and is hosted by me, Morgan Sung.

This episode was produced by Maya Cueva and edited by Chris Egusa, who also composed our theme song and credits music. Additional music by APM. Chris Hambrick is our editor. Brendan Willard is our audio engineer.

Audience engagement support from Maha Sanad. Jen Chien is KQED’s director of podcasts. Katie Sprenger is our podcast operations manager, and Ethan Toven-Lindsey is our editor in chief.

Some members of the KQED podcast team are represented by the Screen Actors Guild, American Federation of Television and Radio Artists, San Francisco, Northern California local.

Keyboard sounds were recorded on my purple and pink dust silver K84 wired mechanical keyboard with Gateron red switches.

OK, and I know it’s a podcast cliche, but if you like these deep dives and want us to keep making more, it would really help us out if you could rate and review us on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you listen to the show.

Thanks for listening.