Episode Transcript

This is a computer-generated transcript. While our team has reviewed it, there may be errors.

Morgan Sung: We are on the heels of yet another battle. The two factions, once united against a common enemy, have been attacking each other for nearly half a decade. And by attack, I mean they’re calling each other cringe. This is the war between Gen Z and Millennials.

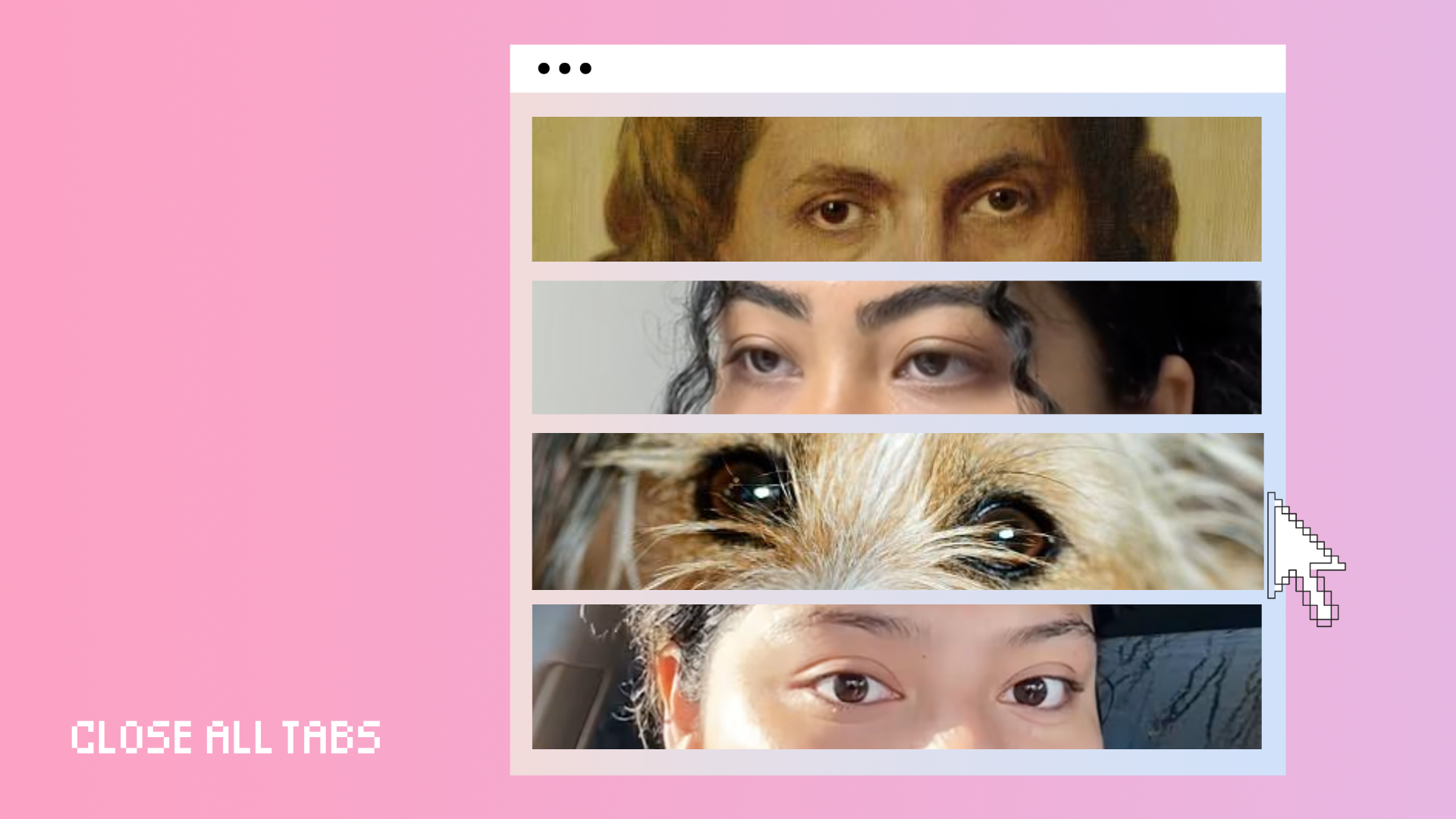

Gen Z is on the defensive in this latest skirmish as they fight accusations of the Gen Z stare. It’s that blank, glassy gaze that young people have in lieu of socially acceptable small talk. On social media, millennials and Gen Xers have complained about the Gen Z stare in meetings with colleagues, in customer service interactions, and pretty much every social exchange in a public space.

Brooke (@nolablest2020): We’re talking about the stare when anyone tries to have just a normal human interaction with you like in the flesh and you guys freeze the f**k up.

Katherine Burleson (@katherineburleson0): People are going back and forth and Gen Z’s like, “No it’s like an are you serious like are you dumb type of stare.” And other people are like, “No it’s almost like a blank look are you even there?”

Morgan Sung: To be fair, sometimes the Gen Z stare is warranted. If you’ve ever worked in customer service, you know exactly what I mean.

Natalie Reynolds (@natalie.reynolds178): Yes, the strawberry banana smoothie does have banana in it, unfortunately.

Morgan Sung: And Gen Z has been making fun of millennials for years, too.

@she_legacy1: Have you guys ever noticed that when older people post videos and by older, I mean like, maybe like 35, 40s and on, they always start the video. They wait like one, two, three seconds to make sure it’s filming and then they smile and then they start talking.

Morgan Sung: Where did this war between Gen Z and Millennials really start? What can this seemingly eternal fight tell us about the ways each generation has been shaped by the internet? And amid all of these petty generational spats, why does everyone forget about Gen X?

This is Close All Tabs. I’m Morgan Sung, tech journalist, and your chronically online friend, here to open as many browser tabs as it takes to help you understand how the digital world affects our real lives. Let’s get into it.

Okay, so I have something to confess. I am a cusper, or zillennial, or whatever you wanna call that generational cohort that was born too late to count as a millennial and too early to really be Gen Z. So in the seemingly eternal war between the two groups, I’ve always been a double agent. Joining me to unpack this generational war today is another double agent, Aidan Walker.

Aidan Walker: So I’d say I’m an internet culture researcher and historian.

Morgan Sung: In addition to his actual academic research on memes, Aidan also breaks down these cultural trends on TikTok as @Aidanetcetera, and on his sub stack, How To Do Things with Memes. Before we get into this generational warfare, I’m very curious, what generation do you most closely identify with?

Aidan Walker: I’m cusp. I’m like between the two. I guess I’m like an elder Gen Z.

Morgan Sung: Same, I’m like, yeah, either the oldest of the Gen Z or the youngest of the millennials. And in my many years of covering this ongoing warfare, I’ve been a spy for both sides. I’ve faking it this whole time.

Aidan Walker: Well, I’ll say this, I’m not sure that there’s specific battles in the Gen Z millennial war that are going to be sung of by the bards. I think it’s often been a cold war at certain points. I think its been kind of like a war of attrition.

Morgan Sung: So we’re going to look at the origins of this cold war, starting with a new tab. The Great Millennial Gen Z War. This war didn’t begin with any public declaration. In fact, this generational tension started way, way before skinny jeans were cringe. Back in 2012, Tide Pods hit the market.

Aidan Walker: They have bright colors. They look like a kind of heart candy. And it’s just the most delicious thing, but it’s also the forbidden fruit of all time because “They,” capital T, “They” tell you that if you eat a Tide Pod, you will be unalived, as a Gen Z person would say.

Morgan Sung: In the years that followed, poison control centers reported that thousands of young children had eaten the tempting, but deadly, laundry pots. Eating Tide Pods kind of became a joke online. And so, by 2018, the Tide Pot Challenge was born.

Dominic Beesley (@dominicbeesley8589): Hey guys, what’s up, Dominic here, and in today’s video I’ll be doing the Tide Pod challenge where you bite into a Tide pod… did you really think i was gonna eat a tide pod?

Morgan Sung: Media outlets warned parents of the lethal Tide Pod craze sweeping the internet. And although some teenagers did actually record themselves trying to eat TidePods, social media and mainstream press coverage very quickly blew it out of proportion.

News Anchor: Well what began as a social media joke is leading to some serious concerns from doctors tonight. It involves teenagers appearing to eat laundry detergent pods and posting the pictures on social media. Photos show the pods being used as pizza toppings or a bowl of them mixed with bleach for breakfast.

Morgan Sung: The vast majority of teenagers were not guzzling down Tide Pods, but they were making and liking memes about being tempted by Tide Pods, which only fueled the hysteria. Some millennials, meanwhile, distanced themselves from the antics of Gen Z. This is where we really start to see the rift between generations form online. The relationship was briefly mended in 2019 when the phrase, “okay boomer” blew up.

Peter Kuli and Jedwill: He gonna take over the mic. Okay boomer, okay okay boomer. Okay boomer. Okay boomer.

Morgan Sung: For a few beautiful months, Millennials and Gen Z were a united front against the baby boomers, or really anyone they perceived as a boomer. It was the perfect comeback. If someone online had a bad out-of-touch take, Millennials on Gen Z would hit back with, “okay, boomer.” For a while, there was peace. And then the COVID pandemic started and the internet evolved.

TikTok: It’s Corona Time! Hey, it’s Corona time right now!

Aidan Walker: So COVID is this moment that disrupts all of our lives. For Gen Z, COVID is this thing that happens before your life has really begun. Maybe you’re in high school, maybe you’re college, maybe you are like the first or second year out of college. And it becomes this thing where you’re like entering the world and you see the world ending kind of in a way.

But for millennials, I feel like they were maybe a little bit more established. And so it became this sudden, like, ghostly pause where you were working from home for a year or two. And I think for both groups, it was very hard in different ways. But I think it’s when you start to see the glaring difference.

Morgan Sung: Yeah, I feel like COVID happened 2020. TikTok is the hottest social media platform and it’s like mostly Gen Z on TikTok.

TikTok: Feelin’ shitty in my bed, didn’t take my fucking meds. The beat, sound to the beat…

Morgan Sung: I feel like that’s when Gen Z started to really gain this kind of cultural capital online. How might that start to stoke the tensions between generations?

Aidan Walker: It changes the format of online culture. It’s now things start on vertical video, then they trickle out to the other platforms. And TikTok is dominated by these young kids, so all these young kids are video editors and they’re able to start putting their own mark on things. I think it really was a moment where suddenly the cutting edge of internet culture is a little bit younger than it was before.

Morgan Sung: Can you talk about this resistance that a lot of millennials had to using TikTok at first, if you remember back then?

Aidan Walker: I remember it because I had that resistance as well. It was the first social media app where I didn’t feel native to it right away. I was just kind of, it’s almost too fast, you know, it had this bad rap, like in the boomer press, people are like, “Oh, it’s Chinese intelligence, mining our data.” And it just sort of felt as if I didn’t t need it in my life, or there would be a bit of a learning curve to get into it. And, uh, of course now I’m, uh… I guess a TikTok influencer to some extent. So I did end up adopting it. But it just was this alienating moment where you sort of realize, “I grew up with the internet and now the internet has grown past me.”

Morgan Sung: We also see fashion trends moving on, like side parts are supposedly out, middle parts are in. Skinny jeans, people are ditching those, like post-COVID, no one wants to wear skinny jeans after quarantine. And moving on from this almost seems like a rejection of like the millennial fashion. How did millennials react to this? Because I didn’t think it was that deep, but if you look at media coverage, it was like, “Oh my God.” You’d expect like a massacre of skinny jeans.

Aidan Walker: Well, it is that deep for some people because I think we have such a weird fixation on youth in our culture. So it’s really an existential crisis for people to feel themselves move from like one demographic category to another. You know, you’re sitting there looking at your skinny jeans and you’ve just turned 30. And it’s like, it’s time to let them go. And it not just that you’re going through that sort of private process. It’s that you see someone 10 years younger than you on TikTok when you open your phone mocking you for it. And so I understand why people felt hurt.

Morgan Sung: Millennials defended themselves with an arsenal of clap back songs?

Alicia Arise (@aliciaarise): I’m about to be a millennial with my side part and skinny jeans.

Serena Terry: So you think we’re old? Well I ain’t having that. We give you wifi and we can take it back

Mikki Hommel (@mikkihommel.music): I was born in 1985, side part and and skinny jeans, and I overused the laugh emoji.

Morgan Sung: By 2022, Gen Z had become very adept at rage-baiting millennials. Rage-bait is exactly what it sounds like. It’s content deliberately made to provoke anger so that viewers respond and it drives up engagement. It’s pivotal in this war between generations.

Aidan Walker: Well, anything that is a controversy does well on the internet. That’s like a fundamental law that everybody knows. And so I think why the generational rage bait begins is first of all, it does numbers for those reasons. And secondly, it kind of helps people to establish their own identity.

You know, this is a time where Gen Z is just distinguishing itself from millennials. And so the way you do that is by, you know, kind of aggressively saying like, “They wear skinny jeans.” Like these sorts of things that may be cosmetic, but you know, when you’re very nascent in figuring out your identity, they mean a lot to you.

Morgan Sung: By the early 2020s, the difference in the way that millennials and Gen Z interact with the internet and with technology also becomes very clear. There’s the dreaded millennial pause, which is that dead air at the beginning of a video before someone starts talking. Usually it’s because they started recording, but they pause to check that it’s recording and they don’t edit that out. And then there’s the inverse, which is the Gen Z shake. Do you wanna explain what that is?

Aidan Walker: So the Gen Z shake, and I’ve seen millennials do it too, so it’s not just limited to that, is when you start a recording, but you kind of do it in such a way that it seems like you just threw your phone down on the table. Like, suddenly you had this opinion about Taylor Swift and you just couldn’t hold it in. You’re about to head out the door, but you press record and the phone’s not even on the the table, and so the entire screen shakes.

And you sit down and you say, “guys,” and you’re just unburdened yourself. And it’s kind of like a faked casualness because you imagine them. You know, setting the phone down on the table several times, you know, over the course of different takes doing this video.

Morgan Sung: But what do these two habits, the millennial pause and the Gen Z shake, of which I am both guilty. I mean, honestly, I’ve done both, I’m not gonna lie. But what can they tell us about the way that each generation performs online?

Aidan Walker: So with the millennial pause, the first thing it tells you is they aren’t as good at editing themselves on video or it isn’t as natural to them. But I think what the millennia pause really says to me is it’s that moment where you see the difference between the offstage persona that is like setting up the recording that is sitting in their kitchen and then the onstage persona that is giving the take that is saying the thing they’ve planned to say.

And because you see that transition, you know that the take is scripted somehow, you know, that it’s the real them, but it’s the them that they’ve curated and made. And it feels almost like someone wearing like an untucked shirt or something to a business meeting. You know, it’s like everybody knows that it doesn’t really matter. But like, you tuck in the shirt, that’s just the way it’s done.

Morgan Sung: Yeah, you go in cap cut and you just shave off your half a second.

Aidan Walker: Yeah, you make it seem seamless so that as a viewer, I can forget that everything is fake. And the Gen Z shake is of course equally fake and inauthentic, but it’s seamless.

Morgan Sung: Though there have been a few developments in the last year, similar to the skinny jeans debacle, crew socks are very popular with Gen Z. Millennials are very defensive of their ankle socks.

But then we also saw millennials taking digs against Gen Z. There was a whole debate over, you know, whether Gen Z is aging faster than millennials did, that kind of thing. And it just feels like every single one of these developments is just like another petty dig that honestly could apply to either generation. What do you think?

Aidan Walker: I think they are petty digs. I think that they tie into real anxieties about aging that people have. I also think it’s worth mentioning that technically generations are fake. They’re a thing we made up. Everything’s a social construct, right? But generations are a little more socially constructed than some other things.

And so I think often what we’re dealing with are these anxieties around aging and then anxieties about social media itself and how it’s changing and how fast it’s changing. And people do get a certain amount of like, identity affirmation out of fighting people that aren’t like them.

Morgan Sung: Speaking of identity groups and anxiety about aging, where is Gen X in all of this? We’ll talk about that after this break. Okay, new tab. What about Gen X? Let’s talk about Gen X throwing their hat in the ring, trying to join the fight. Do you remember Gen X Rise?

Aidan Walker: Yes. It was Gen-Xers venerating their own culture’s uniqueness and importance. It was a lot of like Star Wars. It’s a lot like 80s kid type references. It was lot of Gen X, you know, asserting space on the internet. And I can’t really enter into the mindset of a Gen Xer. But I think a piece of it is they probably have always kind of felt outsiders on this. I think a lot of them only got online maybe in like the late 2010s when it became a mainstream adult thing for people to do and then now they want to clean their little corner of it.

Morgan Sung: I just remember from the trend, it was like in the middle of the whole Gen Z-millennial, you know, going at each other and all these making all these petty jabs. And then you’d be scrolling through all these videos of millennials and Gen Z fighting and then the middle would just be like…

TikTok: Gen X Rise.

Aidan Walker: We’re here, too, like.

Morgan Sung: Basically, yeah. And so I just think it’s very funny that Gen Z and Millennials put aside their differences to fight a common enemy. And by fight, I mean make cringe compilations. Can you talk about how cringe is like wielded in generation wars?

Aidan Walker: Cringe is the weapon of choice in Generation Wars, I would say, calling the other side cringe, compiling examples of them having done it and editing it with like a jaunty soundtrack. Cringe like is always in the eye of the beholder, you know, and so you really I think create cringe by having enough beholders agree with you that it is cringe. There is an element to it though, particularly with millennial cringe. That is centered around like seeing through or around the performance. I’m thinking of like the stomp clap music.

The Lumineers: Ho! Hey!

Morgan Sung: The Lumineers style, right.

Aidan Walker: The Lumineers style, that’s sort of become cringe now because it’s so sincere and yet it’s sincere in a way that it’s overly performative. You aren’t from the holler, you’re like a dude in Brooklyn and that’s what gets cringed is when people try too hard. And then the genius of the cringe tactic as an offensive kind of move against an enemy is that because it’s trying too hard if they try to defend themselves, they’re, again, trying too hard.

Morgan Sung: Going back to Gen X Rise and all that, you know, Gen X is so often forgotten online that it’s become a meme in itself. Why do you think that entire generation is, yeah, just so often overlooked and forgotten about online?

Aidan Walker: I think Gen X is forgotten. I think demographically, they’re smaller than the other generations. So that’s one piece of it. Another part of it is that there’s not as much of like a meme trail there. Like one of the weird things about these fights between Gen Z and millennials is that they kind of like make each other through the fight.

You know, so the things that millennials say, “Oh, that’s a Gen Z trait,” or the things the Gen Z says, “Oh, That’s a millennial trait.” And I don’t know if Gen X was ever that closely watched or faught with by millennials.

Morgan Sung: I also wonder how much of it is like you can’t use cringe against them as effectively because Gen X just doesn’t have as much of a digital footprint as millennials did.

Aidan Walker: We don’t have the receipts, yeah. We have like, yeah, we have like the music video of Kurt Cobain, but we don’t have the posts of all the people trying to do grunge culture on-

Aidan Walker: Yeah!

Aidan Walker: When they’re 15 from their bedrooms, we see it in movies, it’s less raw, there’s less of a record and so Gen X escapes scrutiny that way.

Morgan Sung: Once upon a time, older generations referred to millennials as the lazy, entitled generation. But it seems like every time a new generation ages into young adulthood, it’s their turn to be scrutinized.

And that brings us back to the most recent skirmish in this generational war. The Gen Z stare. Let’s open a new tab. What’s up with the Gen Z stare? Okay, so let’s talk about the Gen Z stare. What is it? How would you describe it?

Aidan Walker: So the Gen Z stare is just…

Morgan Sung: That’s not dead air. Aiden has this vacant slack expression as if he was just factory reset. He’s doing the Gen Z stare.

Aidan Walker: Blank face. You know, someone’s just looking at you just a long pause and their brain is either buffering or processing or they’re dissociating, staring off into space. The context that people saw it most often come up was like customer service type things.

So I guess like the stereotypical interaction would be some millennial or Gen X is like getting a coffee. And then they say they want, you know, sugar in it or something, or like a certain type of pump. And then the barista who’s Gen Z just kind of looks at them.

And so it’s this like, they’re not quite housebroken in a way for like public social interactions is the Gen Z stare. You know, they aren’t able to like interface fully or they don’t recognize when it’s their turn to talk essentially.

Morgan Sung: Yeah, a lot of people have blamed like the pandemic as these like this most formative time in childhood development is, but you’re kept in isolation, you know, and your only interactions are online. But you had your own theory, which you posted about. Can you explain that?

Aidan Walker: Yeah, my own theory was that if the millennial pause is you’re seeing the shift between offstage to onstage, so they’re performing too much, the Gen Z stare is like a refusal to perform. It is a total like, “Okay, I’m not going to make the small talk. I’m not going to ask the follow-up question. I’m just here and people are gonna help me because I’m in public and I’m here, I’m a customer,” or whatever it is.

I’ve been thinking about it in terms of like, if you go to a downtown of like any major city in the U.S. and you go look at the lunch places, they’re all like slop bowl places for the most part. And you think of how much human interaction actually happens, like you could be ordering from a screen. And the idea is just you go and you get your food, you leave. And I think so many public spaces are like that, that the etiquette is essentially like being on a train or a bus. If you’re on the subway and you don’t really talk to people, like that’s not proper.

And I think it’s almost like Gen Z sees all IRL public space like the subway in a way where it doesn’t make sense, you know, to have a small talk interaction, you know, this sort of asocial — COVID being the intensifier of it, you know, when really we were so distant from each other. I think it’s downstream of that. Like Gen Z just doesn’t see public space the same way.

Morgan Sung: Right. I mean, because so much interaction with strangers, with people who aren’t directly in your life just happens online anyway. Whereas previous generations, like, yeah, like I guess boomers and maybe like some Gen Xers were like really into small talk because they didn’t have the internet. They didn’t social media. And now it’s like, well, you’re getting all that interaction anyway, just in a different way.

Aidan Walker: Exactly, yeah, like the example I said in the video was I was at a cracker barrel at this point, like a month or two ago, and I was traveling on the road to elsewhere. And at the table next to us, like a booth next to us, there’s an older couple sitting there, a man and a woman. And another old man walks by and the two old men recognize each other.

And they start having this small talk conversation about, you know, one guy’s brother going into a home and then sort of they’re catching up. It occurs to me that these two old guys don’t seem to know each other very well. I’m almost imagining that it’s the kind of thing like maybe they went to high school together or something in this same small town and they’ve had a marginal relationship their entire lives, have known of each other’s existence, been in the same network, or maybe they were co-workers somewhere before they were retired.

And that this conversation of the two of them talking and taking the time to stop in the cracker barrel to have this pleasantry exchange is actually how this one guy is going to find out about this other guy’s brother going to a home. You know, it’s how they’re going to find out how people they know are doing. It’s how they’re gonna find out what’s happening in the community, because their intel about their social environment is made up of these interactions that happen in these public spaces. Whether it’s Cracker Barrel, whether it’s church, whether, you know, the store.

And the fact that Gen Z doesn’t have that, it sort of occurred to me that, you know, I’m not sure I would have that conversation with someone I knew marginally that I went to high school, but I haven’t really talked to since. I would probably pretend I didn’t notice them in a public space. And it’s because if I want that data, I go on Instagram and I see, okay, she’s getting married. Her fiance looks nice. Haven’t seen her in eight years. Happy for her. You know, like there’s this kind of immediacy, but also it happens through the platforms. You know you no longer need these specially made places for it. And so the Cracker Barrel just becomes a place to eat for me.

So the Gen Z stare is a refusal to use public space as public space. It’s. Treating it as private space, right? You’re just there to get what you want to get to fulfill the particular function. And you’re not gonna put on the front of saying, oh, how was the weather? How are you doing? If you’re just gonna say, how do I get from point A to point B? And you gonna save your emotional labor, I guess your social presentation for the platforms where you actually have more of a chance to control it and more of chance to choose where it goes and who it’s going to.

Morgan Sung: What does the Gen Z stare tell us about… us? Well, instead of being expected to perform social niceties all the time, a lot of younger generations choose when and how they want to be perceived.

But maybe there is something lost in the way we socialize now. Everything online is so curated, and there is some thing about the messiness of spontaneous real-life connections that feels very human. But then again, the Gen Z stare could just be a sign that people are finding this kind of connection online instead.

Let’s be real. Every generation has been hated on and criticized by previous generations. It’s just how things go. But things are different now. The internet and the way we’re constantly consuming and participating in content puts each generation under more of a microscope. It amplifies the tension between each group.

So we often see these arguments end with, you know, Gen Z expressing anger over the current economic and labor conditions that they’ve grown into, you know that they have aged into. But millennials, aren’t necessarily the ones to blame because they also faced very, you now, tumultuous economic and labor conditions when they aged into adulthood.

Aidan Walker: Gen Z probably hates the boomers more than millennials, just as I’m sure millennials kind of know the boomers are… If you, I think if you were to do polling, that’s what people would say would be my suspicion.

But I think the economic angle of it is important because if COVID for Gen Z was this moment kind of before their adult life began, where it kind of threw the whole thing in doubt. And for millennials, it was, you know, they, this sort of hard one stability or you know, first few steps on the path of life that suddenly get derailed or jostled around.

Morgan Sung: So are these markers of cultural conflicts really just a distraction from the realities of, you know, the world right now with these very precarious and unpredictable economic and social changes?

Aidan Walker: I think what makes them feel a little bit more serious is the way that young people feel disempowered today as all these changes are coming down the pike. I mean, not to be like the gerontocracy guy or banging that drum constantly, but it seems like a lot of the people in charge at high levels or even at like medium levels are going to hang on and they have economic incentives to do so as well. You know, it’s getting more difficult to be a retired person.

And so it feels a little like Gen Z and millennials to a lesser extent are through their voices online sort of trying to assert a kind of power that is largely unavailable to them, because our whole lives I think we kind of grew up knowing this tsunami of whatever is coming, whether it’s the AI apocalypse or climate change or whatever is arriving. And it’s like, actually, no, just keep playing on the beach, the adults are going to do something about it. And now it’s sort of like Let us grab the wheel, let us grab the wheel. Come on, guys, and it’s not happening.

Morgan Sung: This whole thing really picked up when Gen Z aged into adulthood and started taking over spaces that had been ruled by millennials. They didn’t just usurp millennial territories, but started carving out new ones too, places that millennials might’ve been hesitant to explore but have eventually settled into. Take TikTok, for example. A Pew Research study last year found that TikTok’s 35 to 49 demographic is actually growing faster than its 18 to 34 users.

But a new faction is gaining power more quickly than millennials or Gen Z ever did. And everyone seems to be a little bit scared of them. They’re built different. They’ve been online since birth. They communicate in emojis before they can even read. And their memes are weirder.

Skibidi Toilet: What the heck is goin’ on, on, you, on Brrrr Skibidibobobobo, yes, yes Skibidibobo the neem, neem

Morgan Sung: It’s only a matter of time before Gen Alpha takes over the internet.

Aidan Walker: I think Gen Z is going to react worse to the rise of Gen Alpha than millennials reacted to the Gen Z.

Morgan Sung: Why is that?

Aidan Walker: Cuz I think for Gen Z, the identity is a little even more tied into the internet than for millennials. I think, for GenZ, they have this sense that, oh, they’re the weirdest, they’re the most special. So I think as Gen Alpha rises and they get into niche memes that Gen Z doesn’t understand, I think that the sense that the meme cultural capital is with Gen Alpha will be much more re-stabilizing. I think Gen Alpha is also much more like, doesn’t need us, and that’s the most annoying thing.

Morgan Sung: They’re so self-sufficient.

Aidan Walker: They don’t need us at all, yeah. They’re like little aliens and they sit there on their iPads or you know watch their Roblox or their Bluey or whatever and there’s just- there’s just no engagement or like need to listen to us.

Morgan Sung: Thank you so much for joining us, Aidan.

Aidan Walker: Thank you, Morgan.

Morgan Sung: Let’s close all these tabs.

Close All Tabs is a production of KQED Studios, and is reported and hosted by me, Morgan Sung. Our producer is Maya Cueva. Chris Egusa is our Senior Editor. Jen Chien is KQED’s Director of Podcasts and helps edit the show.

Original music, including our theme song, by Chris Egusa. Sound design by Chris Egusa. Additional music by APM.

Mixing and mastering by Brendan Willard.

Audience engagement support from Maha Sanad. Katie Sprenger is our Podcast Operations Manager and Ethan Toven-Lindsey is our Editor in Chief.

Support for this program comes from Birong Hu and supporters of the KQED Studios Fund.

Some members of the KQED podcast team are represented by The Screen Actors Guild, American Federation of Television and Radio Artists. San Francisco Northern California Local.

Keyboard sounds were recorded on my purple and pink Dustsilver K-84 wired mechanical keyboard with Gateron Red switches.

If you have feedback, or a topic you think we should cover, hit us up at CloseAllTabs@kqed.org. Follow us on instagram @CloseAllTabsPod, or drop it on Discord — we’re in the Close All Tabs channel at discord.gg/KQED. And if you’re enjoying the show, give us a rating on Apple podcasts or whatever platform you use.

Thanks for listening!