Episode Transcript

This is a computer-generated transcript. While our team has reviewed it, there may be errors.

Morgan Sung: Just a note, this episode includes mentions of suicide, so listen with care. A few weeks ago, I went to a gathering called Open Sauce. Open Sauce is kind of like a maker fair, tech convention, and creator meetup all rolled into one. Every summer in the SF Bay area, engineers, fans, YouTubers, and other tech nerds get together and show off what they made.

RUKA Presenter: Open source robot hand. It’s 3D printed, off the shelf parts. We just kind of wanted to make robot hands an accessible thing.

Lucy M.: An animatronic Richard Nixon face, so there’s a little fine-tuned GPT-4.1 who thinks he’s Richard Nixon.

Tentacle Paradise Presenter: This is a tentacle paradise, so we’re doing a rave with tentacles and we have all these different motors that can control three axes and rotations on these tentacles.

Nick Allen, Voicraft: So this is a nearly six foot tall pocket watch made entirely out of wood.

Morgan Sung: Can I ask why?

Nick Allen, Voicraft: Why make this? And I, you know, I was, I came home from the workshop one night and I said to my wife, if I am asking the question why and the answer is why not, I feel like I’m on the right track.

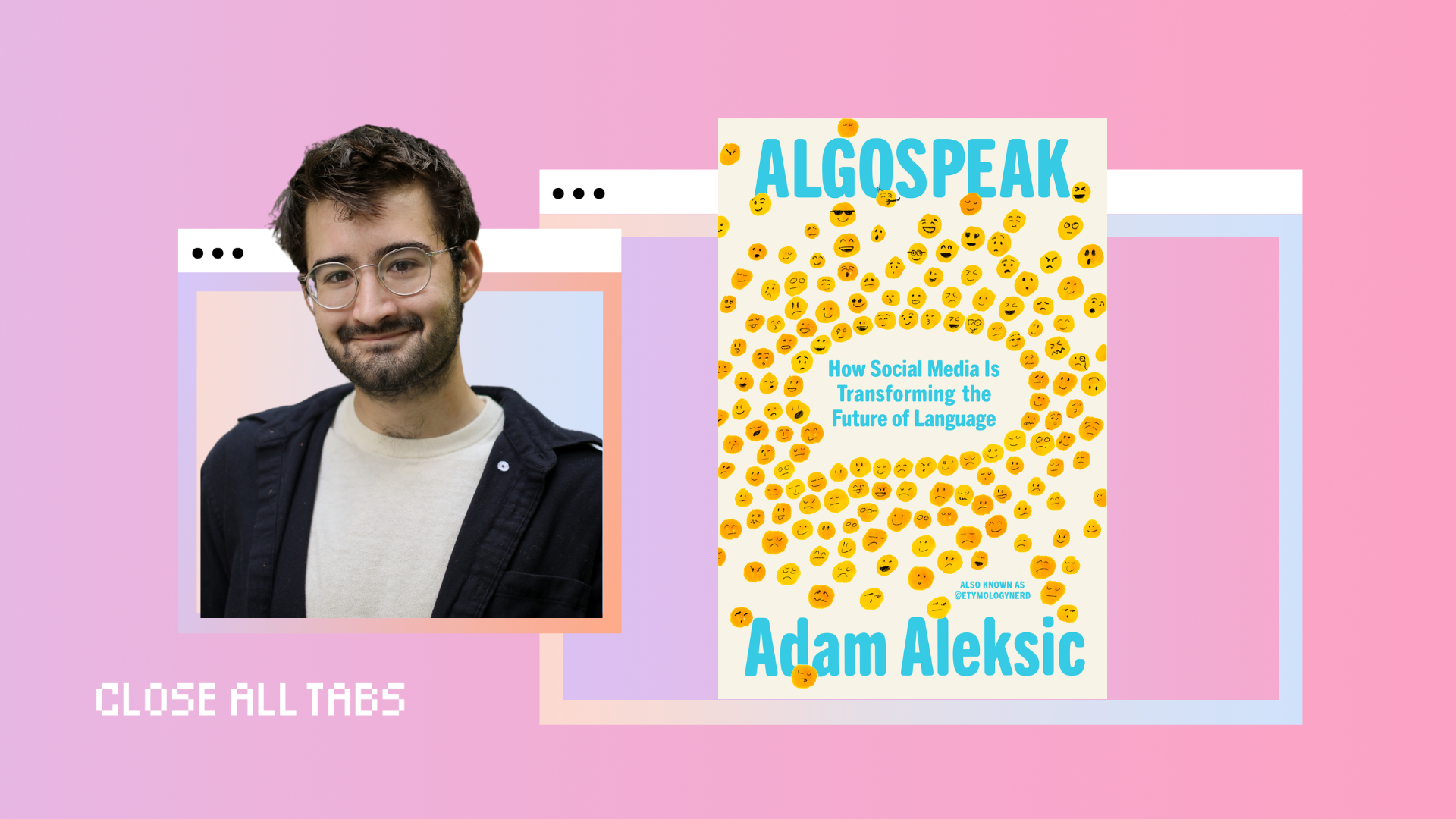

Morgan Sung: So that gives you an idea of what open sauce is like. But I was really there to talk to Adam Aleksic. Online, he’s known as “etymologynerd.” Etymology being the study of how words evolve. You might have seen his videos.

Adam Aleksic: There’s an emerging nerd dialect among math and CS people in elite American universities and tech companies.

Morgan Sung: Adam isn’t just a language enthusiast, he literally has a linguistics degree from Harvard.

Adam Aleksic: They all tend to talk using the same phrases, like non-zero and non-trivial, which come from mathematical proofs but are then applied to unrelated contexts, like, “There exists a non-0 chance we’re out of eggs.”

Morgan Sung: The funny thing is, Adam doesn’t actually sound like that in real life. Here’s how he talks in person.

Adam Aleksic: Yeah, I go as the etymology nerd online. I make content about linguistics, often covering kind of slang words. I’ve been sort of dabbling in the language communication space since 2016. I got interested just for the fun facts, if I’m being honest.

Morgan Sung: So that first version of Adam that you just heard.

Adam Aleksic: You’ll even see this affecting their grammatical structures, like they’ll say such that instead of so that simply because such that is used more in mathematical language.

Morgan Sung: That’s just Adam using his educator, creator voice. It’s a form of algospeak. That’s a play on algorithm and speech. Algospeak usually refers to the coded language that people use online to evade content moderation filters. Think of the way TikTok users say “unalive” because words like “kill” and “die” and “suicide” are suppressed.

TikTok Creator 1: What happens to people who unalived themselves?

TikTok Creator 2: Rammed through a car unaliving six people.

TikTok Creator 3: Whether or not somebody really wants to unalive themselves or not.

TikTok Creator 4: She ends up dating her neighbor who ends up being, secretly, the town serial unaliver.

Morgan Sung: Adam recently wrote a book called Algospeak, and in it, he argues that this phenomenon is bigger than self-censorship. The way that people change their speech patterns to grab your attention, like he does in his videos, the evolution of slang words online, people making language choices to optimize for social media algorithms, all of this is Algospeak. We’re seeing words like “unalive” not just online, but in real life conversations too.

So how does Algospeak make that jump into our offline lexicon? And should we be worried that a handful of tech platforms have this much influence on language? What I’m really asking is, are we cooked?

This is Close All Tabs. I’m Morgan Sung, tech journalist and your chronically online friend, here to open as many browser tabs as it takes to help you understand how the digital world affects our real lives. Let’s get into it.

Let’s open a new tab. Where did algospeak come from?

The phrase “algospeak” is relatively new. It really came about when TikTok took off in the U.S. Around 2019. TikTok uses automated content moderation and is notorious for over policing sensitive topics like conversations about mental health. Words like “kill” or “die” or “suicide” are loaded. Those words might be used when people talk about the news or moments in history or mental health treatment or grief. But sometimes people might use those words threateningly and the content filters aren’t great at telling the difference.

Videos using those words might be flagged or taken down. Some creators also fear getting “shadow banned.” That’s when someone’s content isn’t getting as much engagement as usual because of a content violation, but they don’t get an official warning. So to keep talking about these topics, people online came up with new words.

An infamous example is the phrase, “Kermit Sewerslide.” But “unalive” has been the one that’s stuck. While algospeak is relatively new, humanity has softened language around difficult topics throughout history, like using the word deceased instead of die.

Adam Aleksic: Right, deceased comes from the Latin word for departure. Unalive comes from a 2013 Spider-Man meme that got turned into a Roblox meme. So there’s something a little bit funnier about the word unalive, and I think that’s what’s a little off-putting to people who are uncomfortable with that word that we’re finding the silly way to talk about death. The euphemism part is not new, and we have kids in middle schools actually writing essays about Hamlet contemplating unaliving himself right now. So that’s not new that we are finding new ways to talk death because we’re uncomfortable talking about it.

But I think the widespread pervasiveness of this on social media is because of its mimetic quality as well, that it is a funny word and it’s spread because it was an internet trend. It also spread because of how the internet creates in groups. So it spread through the mental health community on TikTok, particularly as a way to build resources and share their stories.

Morgan Sung: Interesting, yeah. I mean, yeah, how is the all-pervasive, all-knowing algorithm shaping the way that we speak when it comes to euphemisms like unalive?

Adam Aleksic: The most important thing that I would try to emphasize is that all words are metadata right now in the past metadata is like hashtags information about the content at this point. We have natural language processing algorithms taking every single word that’s spoken and appears on screen in your video. They turn that into a piece of information. So every single words a piece information about content and that means savvy creators use their language very deliberately. They use language in a way that generates more comments more engagement, improves user retention.

It’s clear that some words are better at grabbing our attention than other words. If a word is trending, creators will tap into it because they’re trying to hijack that trend. At the same time, because they know that some words will tell the algorithm, “Oh, this video is not going to not something we want to conform to our platform best practices,” whatever. They’ll reroute their language.

Morgan Sung: We’ve seen this kind of thing over and over again. Back in the 1800s, a guy named William Bowdler published a version of William Shakespeare’s plays that replaced anything raunchy or offensive with language that he deemed, “More suitable for women and children.” So in Shakespeare’s Othello, there’s this iconic line.

Iago: Your daughter and the Moore are making the beast with two backs!

Morgan Sung: It’s a euphemism for sex, right? But in Bowdler’s version, Iago says.

Iago: Your daughter and the Moore are now… together.

Morgan Sung: Which just doesn’t hit the same. Bowdler’s version… sucked. So much so that we now have a word, bowdlerization, to describe removing or modifying, quote, inappropriate content. Back in the early 1900s, artists replaced expletives with other symbols so their comics could still be printed in newspapers. That’s bowdlarization at work. And then in the 1980s, we got the internet. The early, early forums started taking off.

Adam Aleksic: Yeah, as early as the 1980s, we saw “leet speak.” There was just very basic text filters of certain words, and people would find ways to evade that.

Morgan Sung: That’s LEET, L-E-E T. It’s a play on “elite,” as in having elite status on bulletin board systems back in the 80s.

Adam Aleksic: Instead of the word porn, people would write pr0n, and the O would be like a zero. Sometimes the letters would be substituted with similar looking letters, that’d be a very common one. Sometimes there’d be just like intentional misspellings. The difference between the internet and this new algorithmic era, I think, is a massive infrastructural shift that’s affecting how we communicate.

So first of all, internet was massive in terms of allowing for the written replication of informal speech. Now more people can have voices. And in the same way sort of algorithms and platforms on social media allow for people who didn’t have a voice in the past to have a voice they can have some positive effects — I think it’s a new tool for using language and every tool has good and bad applications — but we have to remember that unlike the decentralized internet, there’s three companies running short form video. We’re in this kind of panopticon. We can’t separate that from how we’re communicating right now.

All of our communication is baked into these platform structures that they’ve created that incentivize creators to mold their speech around what they want. So you can’t say sex on TikTok, for example. It’ll be suppressed. You’re not sure how many people it will be sent to. So you hyper-correct. There’s doctors and sex educators who will use the word “seggs” instead. The hashtag “seggs education” has 40,000 uses on TikTok.

But more than that, when you’re an educator online and I try to make educational content, I have to package it into sort of a mimetic kind of quality. And this is something you’ve always had as a teacher like to capture your students attention. This has always been true. You’ve had to make the lesson entertaining for your children. I do think algorithms compound and amplify natural human behavior. And there’s more of a need to get people’s attention because you’re competing against every single other thing on the platform, like, that could potentially grab your attention more. So everything’s “edutainment.” There’s no like entertainment versus education.

Morgan Sung: You mentioned, you know, even the word unalive, even that is becoming censored now, which makes me wonder how effective is algospeak and bowdlerization really when it comes to these very sophisticated moderation that the platforms are using?

Adam Aleksic: The analogy I use in the book is linguistic whack-a-mole. So you have a mallet coming down, that’s the algorithm censoring something. And then the new mole pops up, which is humans finding a way to talk about that. And I believe that humans are incredibly tenacious at coming up with new language, finding new ways to express themselves. It’s what we call a productive force in linguistics, something that produces more language. The fact that these algorithms are here mean we’re producing more euphemisms than we otherwise would be. In other ways, the fact that the algorithms create in groups means that these in groups now have a shared need to invent new slang and spread it so everything about the algorithms is making the words happen faster and more intensely than in the past.

Morgan Sung: How does this sort of self-censorship and this need to even optimize your language, how does that affect the way that you talk about linguistics online? How does that effect the way you talk sensitive topics, especially when it comes to like conflicts in Gaza or sex?

Adam Aleksic: Right, well, famously, the watermelon emoji stands in for the Palestinian flag. But at the same time, that comes out of an actual cultural legacy of people using the watermelon because they were banned from using the Palestinian flag during previous conflicts with Israel. So that was a literal example of people, using this signal to circumvent some kind of censorship. Now, it’s been taken in this new context, it evolved into a new sociological condition, but it’s still used to evade censorship.

Morgan Sung: Yeah, I mean, like the algorithm is not transparent at all. It’s like, you don’t know whether or not something’s gonna work until after the fact, until you check your traffic after you’ve posted it. Does that disincentivize talking about sensitive topics, knowing that you have to like play this sort of linguistic whack-a-mole or like, I don’t, dodge these censors?

Adam Aleksic: Possibly, there’s a kind of a practice called “Voldemorting,” which is skirting around a topic. It’s called Voldermorting because, much like in the series Harry Potter, you can’t say the name Voldemort, or there’s the fear of saying the name, Voldemort, so people circumvent that with phrases like, “He who must not be named.” So one creator that I talked about, he wrote about Hitler as the “top guy of the Germans,” because you don’t wanna say Hitler, but you circumvent enough that there’s no chance the algorithm is gonna pick up on that.

Morgan Sung: That practice of coming up with new, creative ways to say something taboo is called “the euphemism treadmill.” This was a phrase coined by Canadian psychologist and author Stephen Pinker.

Adam Aleksic: The idea that once a euphemism gets bleached enough, that means it loses its original meaning, we find a new euphemisms to replace it. So the words idiot, imbecile, and moron used to be actual scientific classifications for people with mental disabilities, but that became like clearly pejorated meaning it took on a negative connotation. And then we moved on by making new terms like the “r slur” which also became pretty bad and we keep coming up with new words because it’s seen as negative, it keeps getting turned into an insult. And we have to find new ways to talk about these ideas. And you know, even now, like autistic, some people use it as a slur or like in an insulting capacity. That’s the euphemism treadmill, we definitely see that happening and accelerated by the algorithm.

Morgan Sung: I mean, I’ve seen this exact thing happen with the word lesbian becoming “le dollar bean” becoming now woman loving woman, and where the word lesbians is almost pejorative. I guess, how does the euphemism treadmill affect the way that we talk about identity?

Adam Aleksic: Right, women loving women is a great example because a lot of people don’t even realize that’s algospeak. It’s so effective at replacing something that — we don’t know how much the algorithm is suppressing discussion of LGBT rights, but it seems to be to some degree, and certainly we know in regions of like the Middle East, you can’t talk about this stuff — so there’s reason to distrust it. I think people over-correct and then end up changing language as a result.

The identity formation thing is a fascinating rabbit hole because the existence of a category can definitionally change your identity. You either identify with this category or against it. And I think social media brings us more categories than we had in the past. There’s a lot of micro labels that were trending on Tumblr, like different genders and different sexual orientations, and even fashion-wise, like different aesthetic micro labels. You could be Cottagecore, Goblincore, Clean Girl Coquette. All of these are like now labels that exist that didn’t exist as much before. Again, they were sort of on Tumblr.

But the algorithm really popularized them and now they’re more in the popular consciousness than in the past. And now when I’m defining my fashion identity, I could have just liked earth tones in the pass, but now I need to figure out whether I’m goblincore or whatever.

Morgan Sung: It’s all marketing.

Adam Aleksic: But now I’m like putting myself in maybe a narrower box than I was before.

Morgan Sung: Last year, the Seattle Museum of Pop Culture got a lot of heat for how it presented its Nirvana exhibit. It included a placard about the 27 Club, a group of artists who have all passed away at 27. Nirvana’s front man, Kurt Cobain, died by suicide at that age, but the exhibit said he “Unalived himself at 27.”

So how did this algospeak phrase end up in a real life physical museum? Let’s get into algospeak moving offline after this break.

How did the term unalive end up in a real museum? That’s a new tab. When algospeak goes mainstream.

So more and more, we’re seeing algospeak break out of online spaces and ooze into real life conversations. For your book, you interviewed teachers about kids using the word unalive unironically. How does this happen? Do those kids know why they’re saying the word, unalive? Do they know that they’re using algospeak?

Adam Aleksic: I think a very important thing to think about is context collapse, the idea that we don’t know where some words are coming from. They’re often reinterpreted in a new way once you see it coming from a new context or when you’re not the perceived audience, like the fact that unalive is being used offline. Some kids didn’t know that was a word for internet censorship at all. They hear it from their friends. They hear from creators, but at the same time, they didn’t that the creators are using it for this purpose. There’s a lot of reasons why we lose context, and when we lose context, that’s how we forget the etymology. When we forget the etymology, that’s how words change meaning.

Morgan Sung: I mean, we always see posts of people saying like, “Oh, this white creator is faking a Blaccent.” And those, they may insist that they’re not, they’re just using internet lingo. How does context collapse play in that kind of scenario?

Adam Aleksic: Well, Blaccent is different. That’s sort of actual intonations and speech patterns. And it’s very hard to accidentally start using that particularly. But individual words, perhaps, you really might not know unless you’re super tapped into etymology, like that slay, serve, queen, cooked, ate, bet, you know, cap. All of this comes from Black slang. And then you replicate it. And the words were originally created as a sort of identity forming mechanism, again, because language is a tool for identity building.

And it was created in this community that needed a way to build identity away from the straight white norms of the English language. A lot of this was from the ballroom slang in New York City in the 1980s. And then it sort of gets repurposed and it loses that power in the original community. Now they have a need to come up with more words and now we’re back in treadmill territory.

Morgan Sung: That euphemism treadmill applies to pretty much every marginalized group online. Like how instead of saying “autistic,” people might use “acoustic” or “neuro-spicy” or “touch of the ’tism.” Autistic creators use these phrases in conversations with other autistic creators to evade filters and as a tongue-in-cheek way to identify others who have had similar experiences. But those terms spread and broke into the mainstream. And with that, context collapse. When in-group language goes mainstream, outsiders might use it pejoratively against the community that created those words.

Adam Aleksic: Well, I don’t think, I think at this point, we’ve stopped saying that or I was never saying that I think it was always kind of strange. It was coined inside the autistic community and the mental health spaces as a way to kind of just poke fun at autism, but for themselves. And then let’s say like, I dunno, like, this is also a natural human phenomenon. Let’s say you are a relative of someone who’s autistic. Is it okay to use that word? Maybe, maybe. You’re, you know, you’re close to the culture. You really do care about it.

But now, now you’re a relative using it and you might say it and someone else might hear from you and think it’s fine to say it themselves. And then that’s how context collapse occurs. With acoustic, it’s one of those funny TikTok words as well that made it more spreadable as a meme. That made it easier to turn negative because it’s just a joke, right? Jokes can like tread into edgy territory.

Morgan Sung: Yeah, when I was reading your book, you bring up a similar thought with, you know, the words “fruity” and “zesty.” And it really reminded me of, I don’t know if you remember in the 2000s, there was this Hilary Duff PSA where it’s like, “You can’t say that top is gay.” And you know and she’s like, “Why are you using gay as an insult?” And yet on TikTok, I always see people saying like, “Wow, looking fruity today.”

Adam Aleksic: Right, yeah. Well, and often I don’t think that’s that negative, but it can be in like a different context. Right. Yeah, like a bully calling someone like fruity while shoving them into a locker is a different context, and now it’s entirely the context with how that word is perceived.

Morgan Sung: So thanks to the internet, language is undeniably changing. We’re seeing the development of the influencer accent intertwined with the way that American Sign Language is changing. Aside from self-censorship. How else have you seen language change?

Adam Aleksic: Yeah, the sign language example is really interesting. I’d like to elaborate on that real quick. Yeah, please go. The fact that people are signing in a tighter box because that’s what the movements that fit on the phone screen are, the fact that like the word for dog used to be like patting your hip and now it’s like higher up because you couldn’t see that on a phone screen as well, or like there’s more one-handed signing than in the past.

All that is kind of like where sign language is going. And that’s again, we can literally see the constraints of the phone molding sign language. And yet, why wouldn’t it be happening with other versions of language as well? The influencer accent, right? These different intonations we have for speaking online simply because they’re more compelling ways to talk for that medium.

Morgan Sung: Can you give an example of the influencer accent? Do a, like, do your impression.

Adam Aleksic: There’s the standard lifestyle influencer like the hey guys welcome to NPR like that kind of kind of rising tone that keeps you paying attention. It’s there’s nothing worse than dead air on the internet and it sort of like fills space and also keeps you kind of the uptalk makes you want to know what’s coming next. I use a different kind of accent I use the educational influencer accent. So I’ll stress more words to keep you watching my video talk faster all that kind of yeah?

Morgan Sung: Yeah, I mean, how are you seeing language change and be optimized and algospeaked almost.

Adam Aleksic: Right, it’s all algorithmic optimization. In the past, you’d have stuff like search engine optimization where people would stuff metadata in a certain way to make their pages rank higher on Google. When I say that all words are metadata though, I can’t emphasize that strongly enough. Because if SEO was a thing people did in the past to get their pages to rank higher, algorithmic optimizations is what we’re doing now. And that means every single word plays a part.

Morgan Sung: The fact that this handful of tech platforms have such immense influence on the way that we communicate does genuinely freak me out, because clearly this is bigger than internet slang. If our speech patterns are getting molded into what’s best for the algorithm, then what else are we unconsciously optimizing? The way we think? The way process feelings?

I have one last tab to open. Chat, are we cook?

I always see discourse about language and how the internet is ruining language, how algorithms are ruining language, we’re losing our roots. You know, a lot of that kind of, you know, hand-wringing. In your professional opinion, as a linguist with a degree, are we cooked?

Adam Aleksic: Well, that’s the last chapter title. I want to first separate language from culture, which maybe is not a correct distinction, but let’s look at language first. There’s nothing ever wrong with one word more than another word, right? There’s no such thing as brain rot for individual words. Words are just like there, you know, and then we can use them for good or bad. That’s where culture comes in. Yeah, neurologically speaking, no word is rotting your brain. So as a linguist, I really want to emphasize that, put that aside.

Language is, however, a proxy for culture. You can see how culture’s shifting with language and culture to me is an individual subjective thing. It seems pretty bad to me that our language is evolving under the auspices of these greedy monetizing platforms that are trying to commodify our attention. And maybe, hey, we can look at literally how language is rerouting to change that maybe be more aware of that and maybe spend less time on these platforms or give less power to what they’re saying.

So the fact that these platforms are incentivizing grabbing user attention, creators now, they’re just trying to make a living, they are trying to get attention themselves, they replicate these sort of platform structures. And you can see how also changes in weighting affect the distribution of content and messaging. Instagram, after Trump got elected, went super racist. I was on Reels before and after, and all of a sudden there’s this really racist AI slop down my feet and how did that happen?

Morgan Sung: It’s like on another level.

Adam Aleksic: Yeah, they change something in the inputs, they change something about what they’re filtering out. And now we’re getting all different content and maybe shifting the overton window of acceptable ideas in a different direction.

Morgan Sung: So going back to your own content, you’re covering very complex, nuanced topics and adapting them to be approachable for the average non-linguist scroller. What have you learned about making this kind of information compelling for anyone?

Adam Aleksic: Yeah, I mentioned edutainment. It’s very important that you package things inside other things that are more compelling, find mediums that work better for certain messages. So it works for me because I am actually academically analyzing where slang words come from. But at the same time, it’s just funny that I’m talking about skibidi toilet and people will-

Morgan Sung: Put Harvard degree to work.

Adam Aleksic: It’s funny because people, you know, recognize that it’s funny, but it’s serious at the same time. So by packaging something serious inside something funny, I can maybe have an impact here.

Morgan Sung: What is the algospeak practice you maybe unconsciously used and caught yourself, you know, using in your own content?

Adam Aleksic: I’ve thought about this a lot with the influencer accent because part of it is conscious, part of it, is, “Alright, I’m going to try to stress certain words right now.” At the same time, an accent is not something you can consciously maintain all the time. It’s like a subconscious thing that you uphold simply because it’s like building a habit or routine.

Once you do it enough, you sort of slip into it naturally. At this point, you know, I’ve sort of trained myself into it by looking at retention rates and seeing what works and thinking about it critically. But at the same time, when I’m actually filming, I’m not thinking about all these things. I just go into a routine and I film my video and I’ve subconsciously done the influencer accent.

Morgan Sung: You know, it’s funny you mention that. I have caught myself doing the same thing where I, the voice I am using on the show is very different from the voice I use when I have to make social videos for the show. But it’s true. You are being perceived very differently.

Adam Aleksic: The analogy I like for the influencer accent is broadcast TV, like TV broadcasters will use a different tone of speech. “This just in,” you know, “Breaking news,” like they’ll talk differently than they do in real life, and that’s normal because they’re accommodating for that medium.

Morgan Sung: You can hear this in the public radio accent too.

Derry Murbles: Welcome to Thoughts for your Thoughts. I’m Derry Murbles filling in for David Parker.

Morgan Sung: Okay, that’s a parody of the NPR accent from Parks and Rec, but it sounds familiar, right?

Derry Murbles: Join us next week when David Bianculli will be filling in for Richard Chang Jefferson, who will be filing in for me.

Adam Aleksic: Right. Well, this is sort of like audience design again. There’s an expected idea of what to perceive. Audience design is an actual concept in linguistics that you are accommodating your speech for your perceived imaginary audience. And that’s what the TV people do. That’s what influencers do. And that what NPR people are doing.

So there’s an idea about what a cultured NPR accent sounds like, and then you do it. Occasionally I get like too into like talking about something and then people are like, “You’re using your influencer accent.”

Morgan Sung: Exactly. All right, last last question for real. What is the big takeaway you want people to walk away with from your book?

Adam Aleksic: Two big takeaways, one, algorithms are a new medium that are affecting every aspect of how language changes right now. Two, now that you’re aware of these things, now that your more critically informed, hopefully make your own choices about how to use language.

Morgan Sung: Thanks so much for joining us. I have started to think about the ways that I unconsciously incorporate algospeak into my day-to-day speech. And that, maybe, for the sake of the algorithm, I should be more intentional about using it on the show. When we started developing this podcast, I did play around with the NPR accent.

From KQED studios and the depths of the internet, it’s time to close all these tabs.

And that felt weird, but maybe I’ll give the influencer accent a go.

Hey, tabbers, you’ll never guess what we’re doing now. We’re closing all of these tabs.

Or I’ll try Adam’s educator-creator accent?

Hey, fun fact! Did you know we’re at the end of the episode, and that means it’s time to close all these tabs?

But you know what? For now, I’ll stick with my own. Let’s close all of these tabs.

Close All Tabs is a production of KQED Studios, and is reported and hosted by me, Morgan Sung. Our producer is Maya Cueva. Chris Egusa is our Senior Editor. Jen Chien is KQED’s Director of Podcasts and helps edit the show.

Original music, including our theme song, by Chris Egusa. Sound design by Chris Egusa. Additional music by APM. Mixing and mastering by Brendan Willard.

Audience engagement support from Maha Sanad. Katie Sprenger is our Podcast Operations Manager and Ethan Toven-Lindsey is our Editor in Chief.

Support for this program comes from Birong Hu and supporters of the KQED Studios Fund.

Some members of the KQED podcast team are represented by The Screen Actors Guild, American Federation of Television and Radio Artists. San Francisco Northern California Local.

Keyboard sounds were recorded on my purple and pink Dustsilver K-84 wired mechanical keyboard with Gateron Red switches.

If you have feedback, or a topic you think we should cover, hit us up at CloseAllTabs@KQED.org. Follow us on instagram @CloseAllTabsPod Or drop it on Discord — we’re in the Close All Tabs channel at discord.gg/KQED. And if you’re enjoying the show, give us a rating on Apple podcasts or whatever platform you use.

Thanks for listening!