Episode Transcript

This is a computer-generated transcript. While our team has reviewed it, there may be errors.

Morgan Sung: So on this show, we often talk about how people interact with new technology in surprising ways, like attacking Waymos or using VR to memorialize their loved ones. But we also think it’s important to look back at how we got here today. And one way to do that is to acknowledge what we’re calling “the OGs of tech”, the often overlooked people who paved the way for this digital age. Like the technicians who kept semiconductor equipment running, or the female switchboard operators who pioneered workplace equality.

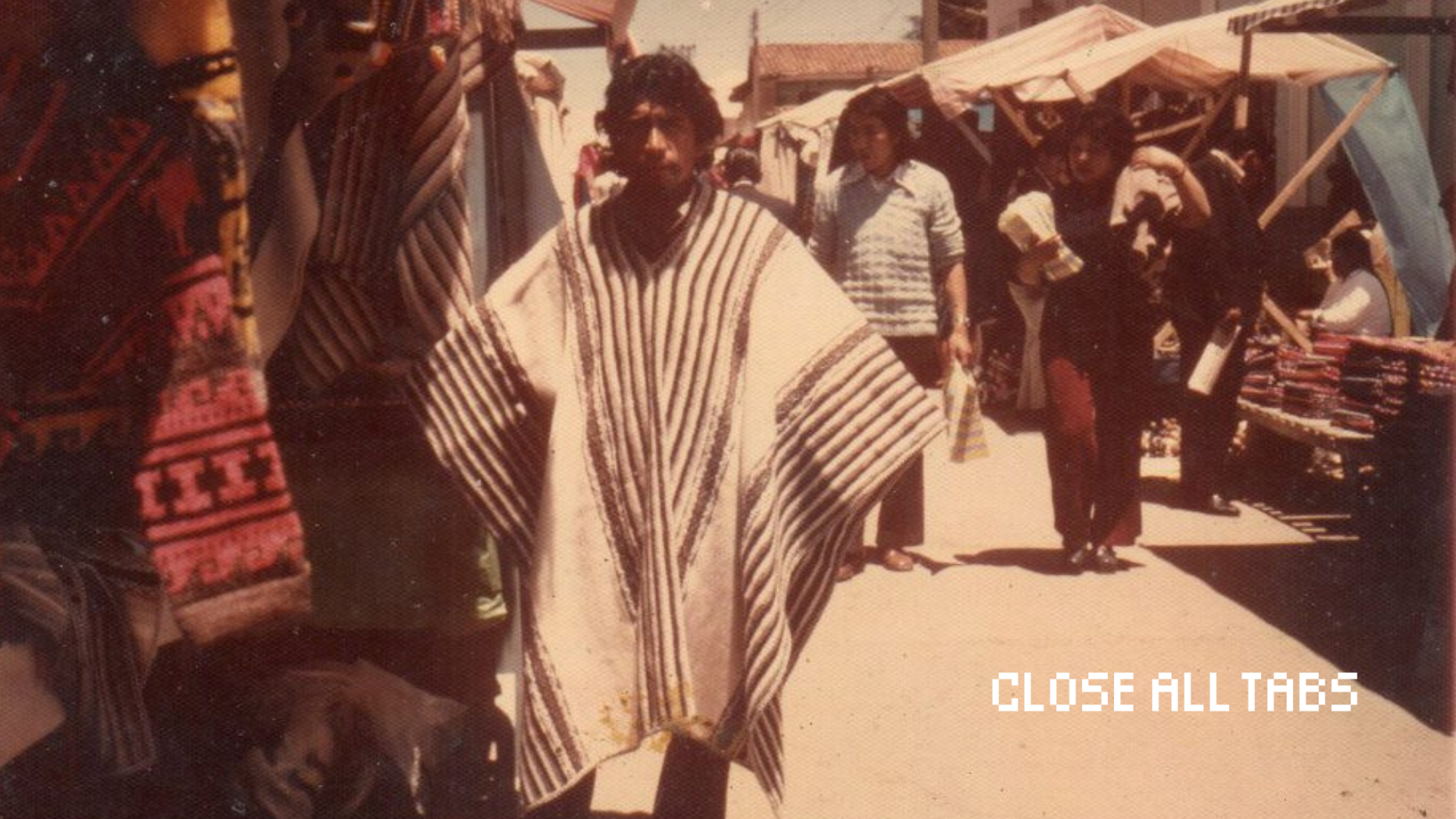

It’s more than a history lesson. Understanding the people who built this industry and the challenges they faced, especially if they weren’t straight white men, helps us better understand the stories we cover today. One of these OGs is Felidoro Cueva, who grew up in a rural village in Peru in the Andes Mountains. Felidoro, who goes by Feli for short, immigrated to the U.S. in 1964 — during the height of the Civil Rights Movement and the Vietnam War — and became one of the first Latino engineers in Silicon Valley.

Morgan Sung: He’s also our producer, Maya Cueva’s dad. This is Close All Tabs. I’m Morgan Sung, tech journalist, and your chronically online friend, here to open as many browser tabs as it takes to help you understand how the digital world affects our real lives. Let’s get into it.

Our producer, Maya, is going to lead this deep dive. Hey, Maya.

Maya Cueva: Hey, Morgan.

Morgan Sung: So I’m really excited to hear this story because it seems like the ones I grew up hearing. Both our dads immigrated to the US, and my dad also got his start in tech many, many years ago. And Maya, you’ve recorded your dad’s story before, right?

Maya Cueva: Yeah, I actually interviewed him for an animated documentary I directed called, Only The Moon, about his immigration story. And I also did a piece for Latino USA about my family’s Latino and Jewish roots. But honestly, it wasn’t until I started working on Close All Tabs with you and Chris that I got really curious about what it meant for him to be a pioneer in tech, especially as a Latino man in an industry with very few Latinos.

Morgan Sung: Yeah, this feels especially relevant now in this political climate.

Maya Cueva: Totally. As we’ve seen, this is a time of increasing anti-immigrant actions. And honestly, I think it’s really important to acknowledge how immigrants have contributed so much in this country and specifically to the tech innovation that we now take for granted. Honestly, I feel like this is a chance to tell one of those stories. And it’s wild that I’m now a producer on a tech show. It sort of feels like he paved the way for me to even have this opportunity. My dad worked on foundational computer technology, like microchips and transistors.

Morgan Sung: I can’t wait to hear about it. So I’m going full passenger princess for this episode and you’re gonna drive us through the story. Ready?

Maya Cueva: Let’s do it, Morgan.

Morgan Sung: Take it away, Maya.

Maya Cueva: Let’s open our first tab. Meet my dad, Felidoro Cueva.

Feli Cueva: I’m originally from Peru and I’ve been in the US for most of my life and I have two daughters and one of my daughters is Maya Cueva and she’s interviewing me right now.

Maya Cueva: Do you feel like you know why I’m interviewing you?

Feli Cueva: My feeling is that you’re having some kind of podcast about technology and, um, you know, maybe Brown, native people.

Maya Cueva: Sure.

Maya Cueva: As you can hear, my dad likes to make jokes. I’m sitting with him at my parents’ house in Berkeley, California. It’s the home I grew up in. My dad is sitting low in a chair I’m hoping doesn’t squeak as he moves. As he talks, his hands move with him, and I notice they are now wrinkled with age. I think about how much he’s been through, worked on, and survived with these hands. Growing up, he was and still is always the one repairing and fixing the tech in the house. When I was younger, I don’t think I really understood just how different my access to technology and resources were from his own when he was growing up. So I asked him about it.

Feli Cueva: I grew up in a very rural environment in which there were no cars, no machines available. In the time when I grew up there was no idea of what computers are. We used cows to till the soil, you know, bulls to till soil and all that stuff. So all the time I basically grew up in a farm. I, you know, I had never seen a car in my village. Cars came when I was already more or less a teenager. That’s what cars start showing up in my area.

Maya Cueva: My dad says that when he was young, the lack of technology around him actually kind of made him afraid of machines, especially cars. They seemed so powerful, so hard to control. He had this recurring dream. He would hitch his mule to a car and let it pull him while he sat behind the wheel.

Feli Cueva: So that was a very comfortable dream actually because then, then I could do whatever was supposed to be done with cars, but I didn’t have to deal with the machinery.

Maya Cueva: That fear of machines eventually turned into fascination many years later, after he left Peru.

Maya Cueva: Do you feel like you remember the first time you heard about a computer? What was the first time that you used one? Can you remember?

Feli Cueva: I bought my first computer, actually. It was a PC, uh, with the lowest memory you could have. And, um, when I bought this computer, I got so concentrated in the program that the computer had, which was called BASIC. And I started doing computer graphics with it, and I was totally fascinated by what you could do with one pixel, controlling one pixel in the screen, and then making a complete program from there. So you actually have a complete image moving in the screen. You and the machine become one entity in a sense for the time you’re immersed in it.

Maya Cueva: O k, clearly, my dad is nerding out over this stuff. But how did he go from being tech-phobic to being totally enchanted by technology? That’s a new tab. Feli’s immigration story.

Maya Cueva: My dad was born in 1944 and grew up in a small village in the mountains of Peru called Ayabaca. He was a curious kid and very studious. Though he was afraid of some machines, there was one piece of technology that he couldn’t resist. It was a shortwave radio and it opened up a whole new world to him. Here he is describing it in my documentary, Only The Moon.

Feli Cueva/Only The Moon: I had a shortwave radio which broadcast news from all over the world.

Voice of America: July 23rd.

Feli Cueva/Only The Moon: BBC, Voice of America, Radio Havana, Radio Moscow. What I remember hearing was the different news, the politics, the fights they were having. Voice of America would call Cuba, “communist. “

Voice of America: In the Western Hemisphere at Havana…

Feli Cueva/Only The Moon: And Radio Havana would call them, “aggressive imperialists.” Basically, the radio exposed me to the world, outside of myself, outside of the village.

Maya Cueva: He soaked up that knowledge eagerly. It left him ready for an adventure.

Feli Cueva: My third year of high school, I got sort of a thirst for knowledge. I became first in class, started learning English, and I would talk to myself, I’d talk to plants, animals in English. I realized after, you know, after English, I realized that I really like languages because I mean, I learned French here, I was learning Russian for a while because I was working for Russian engineers in the U.S. in the beginning of my career.

Maya Cueva: To me, that’s why you liked computers so much. It was like a language in itself.

Feli Cueva: Oh definitely, I think that’s definitely a link there. You know, it’s a communication language like everything else.

Maya Cueva: My dad’s fascination with learning English in Peru would pay off. During his last year in high school, an anthropology student from the University of Chicago came to my dad’s school on a research trip. My dad teacher had him help the visiting student translate newspapers from Spanish to English. My dad and the American student got along so well that they created a bond. After some time in Peru, the student returned back home to the U.S.. My dad continued on with his studies, and then…

Feli Cueva: One day, when I was actually just finishing school, he sent me a telegram saying that if I want to come to U.S., there will be an opportunity for me to come. Basically, my school, they got together with the church and just, you know, just collected a bunch of money for me and it was almost like a fate kind of experience.

Maya Cueva: What was it like for your family?

Feli Cueva: Well, my mother, when I was ready to come, my mother was crying and crying and crying, you know. But my father was, you know, like sort of similar to my behavior, sort of stoic about it.

Maya Cueva: My dad arrived in the U.S. In 1964. He was only 18 and first settled in Chicago in the suburbs, staying with the family of the student who visited his village. It was winter and so foreign to him.

Feli Cueva: I was not even sure where I was going to stay or go. It was for me a big adventure, just the fact that I was coming of a different society.

Maya Cueva: Part of that adventure was becoming immersed in a completely new culture and way of living. But the mindsets of people he encountered surprised him. My father began to notice that even though the family he stayed with had a TV and access to information, they seemed pretty misinformed. He even used the word brainwashed.

Feli Cueva: I realized that lots of the information that people were receiving was mainly from television because they were, you know, even the newspapers they were too tired to read them after they came from work. So the television kept basically gave you no information at all. I called them “the caveman with technology” and that was my first classification of this society.

Maya Cueva: What do you mean by that?

Feli Cueva: In terms of social behavior, social consciousness, it seemed like they were very just controlled by the media, by the immediate media they had. There was no information. It was very advanced society in terms of technology, but yet socially it seemed to me didn’t seem to match.

Maya Cueva: In a lot of ways, I get what my dad is saying. Even today, it can often feel that even though we have so much access to information in the U.S., misinformation is rampant, leaving little room for critical analysis. At the time he came in the early 60s, social and political awareness was just beginning to grow more widespread. And as he started studying and working, his world was also expanding.

Feli Cueva: I started working at the University of Chicago as a laborer, basically doing photo duplication. It was basically putting newspapers, magazines and all that into microfilm. And probably that was where my exposure to the world became because I had to photograph all the newspapers and the magazines from different parts of the world. So that was my total education I got from that.

Then I started looking for uh ways to study. I started taking courses first for English. I started taking courses in YMCA, you know, because that’s where all the foreigners were learning the language. And that was a really good experience because you get to talk to people from all over. After that, I um, I went to Illinois Institute of Technology. I start taking courses there because I could take them at night because I was working during the day. So I started taking chemistry, physics, math, algebra. Basically, I started an engineering curriculum without realizing that I was doing it.

Maya Cueva: This was now the mid 60s. The Vietnam War was escalating, and the Anti-War and Civil Rights Movements, as well as other protest movements, were in full swing. And he embraced this counterculture by expanding his mind in other ways. When we come back from the break, my dad goes on a trip.

Ok, we’re back. Living in Chicago in the 60s changed my dad dramatically. He grew out his hair and beard, kind of resembling a young Che Guevara.

Feli Cueva: All the movements start taking place from all the students, everybody gets involved. Also in the process of uh the movement itself, there are lots of people experimenting with, uh, basically what they call drugs, you know.

Maya Cueva: What they call drugs?

Feli Cueva: Yeah.

Maya Cueva: What do you mean they were drugs!

Here’s another clip from my documentary where he describes his first acid trip experience.

Feli Cueva/Only The Moon: The telephone had become gigantic. I could not pick up the telephone. The television was in the background and Nixon was on the on television and it looked like he was a complete puppet.

Richard Nixon: A deep concern to all Americans and to many people in all parts of the world, the war in Vietnam.

Feli Cueva: The fact that I was introduced to that, it opened my mind because coming from a village, I had no, no concept of the world outside of me. And when I came to that experience, my mindset got changed dramatically.

Maya Cueva: My dad says that being exposed to hallucinogens inspired him later when he started experimenting with computer graphics on his first PC.

Feli Cueva: When you are on drugs, you could, you know, you enter in those kinds of worlds, but it’s not real. But when you actually get into computers by controlling an image on that screen, you could create those images yourself. Start creating all these images, these graphics, which move in the screen, all this stuff.

Maya Cueva: So cool. So you could like make it tangible, like the mind altering became tangible because you got to like —

Feli Cueva: I think that’s what computer graphics became, at the end, the fact that that experience from those, from all that time in the 60s, moved people to so many, you know, ways of communication, really, to creating movies, to creating all these graphics and all these virtual worlds and you know. That’s my take on the whole thing.

Maya Cueva: It does make me sad that, as my dad was creating new experiences in the U.S., the distance from his family in Peru only grew. For a long time, I resented that we didn’t have much connection with that family growing up. While my dad went back to visit over the years, his new life in the U.S. took over. And his village became more foreign as he began breaking into the tech industry. My dad’s first job in tech in Chicago was at a company called Guardian Electric, where he tested electromagnetic switches, the little components that help turn machines on or off. It wasn’t glamorous, but it got him in the door of the industry. His boss was a Russian engineer, and although they spoke different languages, they created an unspoken bond.

Feli Cueva: It was like broken English for both of us in a sense, but he was a very sharp mechanical engineer actually.

Maya Cueva: After that job, my dad moved to a subsidiary company of AT&T, where he tested integrated circuits and microchips for early computers. These are the foundation of modern computing.

Feli Cueva: But the computer at the time was more like, it was a refrigerator sized with very little memory. So it’s just a very simple little programs to test it. You know, I learned a lot because it was fun. You know just learning something totally different while you get paid, you know, which is important and to get paid is important.

Maya Cueva: Right.

At this point, it had been 15 years since moving to the U.S. My dad had broken into the tech industry. He learned some of the engineering basics and even started programming. But he decided it was time to move because there were more opportunities for tech jobs in the Bay Area.

Feli Cueva: I decided to just leave Chicago. So after I worked at AT&T, in the year about ’79, I came to California.

Maya Cueva: In California, he reconnected with my mom, who he had been friends with in Chicago. They fell in love and eventually got married. It was the tech boom at the time, and California was a world full of startups. In 1981, he started working in Silicon Valley doing tech support for a company that made networking hardware to connect PCs and Macs. Apple had only been around for a couple of years at that point. Imagine a board that would plug into both machines and allow them to talk to each other. It was a way to share data and information. He spent a lot of time answering phone calls.

Feli Cueva: So I changed the name from “Tech Support” to “Psychotech Therapy.”

Maya Cueva: Why did you say that?

Feli Cueva: So people would call, especially people from New York, they would call and they were very upset at me that uh, as if it was my fault, you know. And, uh, they started screaming at you first, they want to sue the company because things are not working the way they’re supposed to. They heard my accent, they were asking for an expert, they want an expert because my accent was, I guess, not good enough for them or whatever.

Maya Cueva: How did that make you feel that they were asking that?

Feli Cueva: I mean, discrimination, I experienced a lot from Chicago just by being in the street, more from the police that would stop me constantly for driving. I would get so many tickets all the time because they would just stop me for walking in the streets — they wouldn’t give me a ticket for walking the street — but they always questioned me what I’m doing there.

I guess, you know, tech support, when I got introduced to that process of being discriminated for speaking with an accent. They would call me, they asked me for an expert, who knows how to solve the problem. So I said, tell me what the problem is, and I had to find the right expert for you as if, as if we had a big company of people dealing with it. And then I ask other questions and say, “have you tried this?” And that would solve the problem, so I pretend there was, there was lots of experts working.

Maya Cueva: So you were like, “I’ll go get an expert”, and it was just you.

Feli Cueva: The expert was me, you know, but since they would not believe that I was the expert, so.

Maya Cueva: What was it like to be first like a Latino man in tech in Silicon Valley? Did you see a lot of people who looked like you?

Feli Cueva: Coming to California, I was probably the only Latino working in tech. But you know, but there were a lot of Latinos doing the cleaning and all these stuff, and you know working in the office, or you know in that, but not in that technology side that I work with. At least one time, this other engineer who was, you know from the U.S., he was white obviously, but he sent me to open some boxes. And in fact, I had a degree, and he didn’t have a degree even, you know, but what happened is he confused me with a guy who opened the boxes, you know, who basically does the labor work in the office. And so I told him, you know, “is he busy or what? Why doesn’t he open his own boxes?” And he was shocked, I would talk to him that way. And then he soon realized that he made a mistake and he tried to apologize, you know, but that’s the first experience I had with somebody who just thought I would be a laborer and just not an engineer at all.

Maya Cueva: Just because you were brown.

Feli Cueva: Yeah, that had to do with being Brown, of course.

Maya Cueva: How did it make you feel that he said that to you?

Feli Cueva: I just felt sorry for him, for not really understanding anything, because that’s one problem people have, is that they don’t have exposure to other cultures.

Maya Cueva: It bothers me that my dad had to be the bigger person in this instance and have empathy for the engineer who was racist towards him. But I understand that in his experience, he was able to change people’s minds just by talking to them. A skill that is hard to come by.

Feli Cueva: I had experience in which people, after I talked to them for a while, they actually changed their minds about how they feel, how they see the world.

Maya Cueva: My dad has always been an optimist. It’s representative of the optimism that has been part of the Silicon Valley tech scene from the very beginning. That idea that “innovation can save the world.” But it’s not lost on him how much technology has changed and how it’s changed us. I think that’s time for a new tab.

Maya Cueva: Say, let’s open a new tab.

Feli Cueva: Let’s open a new tab.

Maya Cueva: Can you say us versus the machine?

Feli Cueva: Us versus the machine.

Maya Cueva: It sounds like ass.

Maya Cueva: Us versus the machine. My dad worked in Silicon Valley from 1981 to 2008. In the late 80s and early 90s, my older sister and I were born and were lucky enough to grow up and stay in Berkeley because of his years working in the tech boom. But he says that despite being in such a rapidly expanding field, he always felt like an outsider.

Feli Cueva: In my time, I was involved just in working, I felt like a high-tech migrant worker. I was making good money, but that’s how I felt. I was more like an outsider within the system.

Maya Cueva: You said a high-tech migrant worker? What does that mean?

Feli Cueva: Well, it’s just, you know, basically I’m Latino, so there were lots of migrants working the houses, building the farms and everything else, but I was basically a Latino guy with an engineering degree, so I felt I was a migrant worker myself, even though I was a [inaudible] and all that, but I still had the same feeling, you now, because I was never really part of that, society of technology.

Maya Cueva: His experience echoes some of my own conflicted feelings about Silicon Valley. I grew up hating how the tech industry gentrified my hometown and the Bay Area at large, and also angry at how my father was discriminated against. At the same time, my family has benefited from the growth of that industry, which my dad played a foundational role in. He got to see the world expand in more ways than one.

Feli Cueva: I was basically a part of a revolution without realizing it. There was a revolution of the 60s, and then the other revolution was without really thinking, was actually in technology, because everything was changing. Now we start working from the rudimentary technology of from vacuum tubes to transistors to the integrated circuits, the chips, microprocessors, then computers, now AI. So, you know, I being involved in all that stuff without actually even thinking about it.

Maya Cueva: Does it ever make you frustrated to like learn the new technology?

Feli Cueva: Well, I can’t learn, it’s too much. Yeah, I prefer to just take a walk.

Maya Cueva: So yeah, Morgan, that’s my dad’s technology.

Morgan Sung: I feel like I learned so much. What do you want people to remember from this episode? What can we learn about the industry we cover today by looking at the past?

Maya Cueva: Honestly, I feel that my dad’s journey and the sacrifices he made really shapes the person I am today. I mean, I think a lot of children of immigrants can relate to that, but I do think it’s important to recognize that the new tech stories we cover don’t happen in a vacuum, and tech innovators aren’t all white men.

Morgan Sung: Obviously, things in the tech industry have changed a lot since your dad first started, but like we’ve talked about on the show before, there is a real backlash against social progress or so-called wokeness right now. Some of Silicon Valley’s most vocal leaders believe that it holds back innovation, but stories like your dad’s pushed back against this whitewashed narrative of tech history.

Maya Cueva: Exactly. It’s honestly inspiring to me that my dad was able to start a new life where everything was foreign. He was a part of tech innovation and was also able to raise his political consciousness and the consciousness of others around him. And before interviewing him I didn’t even know he helped test some of the early models of computers we now use today. It really feels full circle. He was working on early tech and now I get to report on it with you.

Morgan Sung: Yeah, and it’s also so interesting that he was there at the very beginning, and he still feels out of touch with the latest technology.

Maya Cueva: Yeah, well I should mention that he actually has gotten into making AI videos. Oh no! Yeah, like the one he sent to the family group chat of my mom flying through the air.

Morgan Sung: My dad does that too. Dads just can’t resist the AI video.

Maya Cueva: Does he really do that?

Morgan Sung: Yeah, my siblings and I have to like yell at him, explain the environmental impact, but another deep dive.

Maya Cueva: Yeah, it was kind of creepy, but I’m glad he gets to have a creative outlet in tech.

Morgan Sung: I love that. So, Maya, are you ready to close these tabs?

Maya Cueva: Yeah, let’s close all these tabs.

Morgan Sung: Close All Tabs is a production of KQED Studios, and is reported and hosted by me, Morgan Sung. Our Producer is Maya Cueva. Chris Egusa is our Senior Editor. Jen Chien is KQED’s Director of Podcasts and helps edit the show.

Original music, including our theme song by Chris Egusa. Additional music by APM.

Sound design by Maya Cueva and Brendan Willard. Mixing and mastering by Brendan Willard.

Audience engagement support from Maha Sana. Katie Sprenger is our Podcast Operations Manager and Ethan Toven-Lindsay is our Editor in Chief.

And we want to send out a special thanks to founding producer Xorje Olivares, who helped define and create the show at its very first stages. We’ll miss you, Xorje!

Support for this program comes from Birong Hu and supporters of the KQED Studios Fund.

Some members of the KQED podcast team are represented by The Screen Actors Guild, American Federation of Television and Radio Artists. San Francisco Northern California Local.

Keyboard sounds were recorded on my purple and pink Dustsilver K-84 wired mechanical keyboard with Gateron Red switches.

If you have feedback, or a topic you think we should cover, hit us up at CloseAllTabs@kqed.org. Follow us on instagram at “close all tabs pod.” Or drop it on Discord — we’re in the Close All Tabs channel at discord.gg/KQED. And if you’re enjoying the show, give us a rating on Apple podcasts or whatever platform you use.

Thanks for listening!