Episode Transcript

This is a computer-generated transcript. While our team has reviewed it, there may be errors.

Katrina Schwartz: Japanese baseball players are hot. I don’t mean that the way it sounds.

Really, Major League Baseball’s current champion, the Dodgers, have three pitchers from Japan.

The most famous right now, Shohei Ohtani, was the League’s Most Valuable Player last season.

Sound of an Ohtani strikeout

Earlier this year, the retired outfielder Ichiro Suzuki, who played in Seattle, New York and Miami, was voted almost unanimously into the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Sound of broadcaster excitement over Suzuki hit

These are players who came from Japan to play baseball in the U.S. But there were Japanese people playing baseball here more than a century ago. They had teams that played against each other and even hosted teams from Japan.

And one of those teams came from the island of Alameda.

In the place that used to be the team’s field, there’s now a modest plaque marking what would have been home plate.

Sam Hopkins: Nothing that really would stand out too much…

Katrina Schwartz: Still, it caught the eye of Bay Curious listener Sam Hopkins when he was out on a run.

Sam Hopkins: But I paused real quick and read it and noticed it was commemorating this baseball field for a Japanese American team that I had never heard of before. Alameda is a really big baseball town.

Katrina Schwartz: Sam grew up playing baseball in Alameda and knows all about the great ballplayers who came from there. The Hall-of-Fame hitter Willie Stargell has a street named after him.

Sam Hopkins: But I’d never heard of this Japanese American baseball field, didn’t know it existed and it just had me wondering who were the teams that played there and what happened to those teams.

Bay Curious theme starts

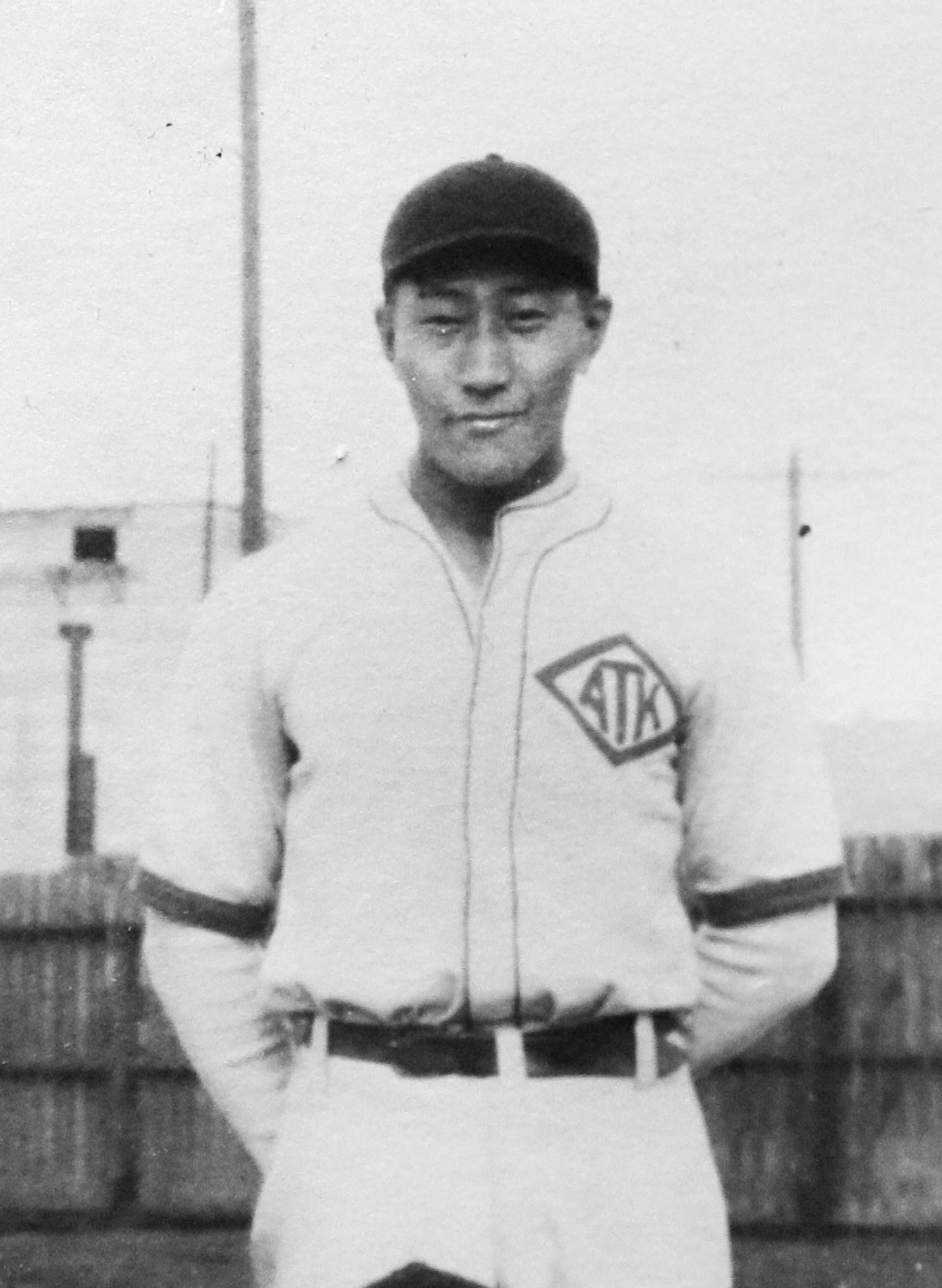

Katrina Schwartz: The team that called the field home was the Alameda Taiiku-Kai. Today on Bay Curious, we’ll learn the history of the team and its star players, and get into what they meant to Alameda’s Japanese American community. I’m Katrina Schwartz; stay with us.

Bay Curious theme ends

Sponsor break

Katrina Schwartz: The island of Alameda has a long tradition of producing great baseball players. And in the early 1900s, some of them were Japanese American. But the early 20th century was a difficult time for this community. KQED’s Brian Watt went to see what role the game of baseball played in that history.

Brian Watt in scene: Sam’s right about that plaque. I came out here to see it, and it is pretty easy to miss if you’re not looking for it. It sits on a rock across the street from Thompson field, about a block from the estuary between Alameda and Oakland. Here’s what is says:

Brian reading: ATK baseball field. Alameda Taiku Kai. During the years 1916 to 1938, this was the approximate location of home plate of the Alameda Japanese American ATK baseball field.

Brian Watt in scene: Alameda Taiiku Kai basically means Alameda Athletic Club. But what I’m really stuck on here is the years: 1916 to 1938. That’s basically the middle of World War I until right before World War II started.

There are no players from that ATK team alive today, but there are people who knew some players — Japanese Americans who grew up in Alameda and still live here.

Kent Takeda: Brian, Kent Takeda.

Brian Watt in scene: How’s it going? Good to meet you. Good to meet you too. Thanks so much. Oh, this is so great. I’ll close it.

Jo Takata: Oh my gosh, I listen to you. I’m Jo, and this is my house.

Brian Watt in scene: Hey, Jo.

Jo Takata: Let me look at you.

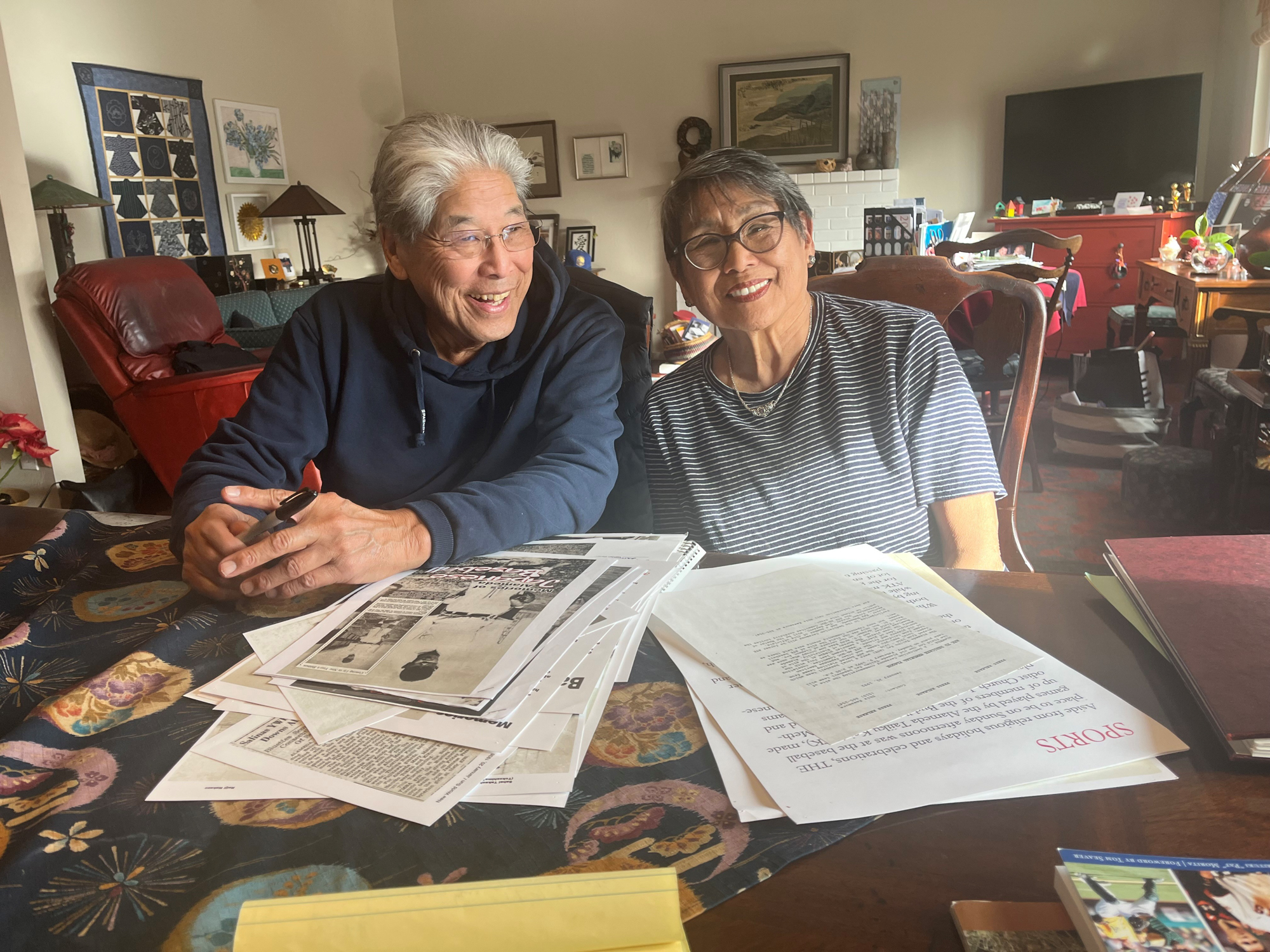

Brian Watt: Jo Takata invited me to her home just a couple miles from the plaque, to meet her and her brother, Kent.

Jo Takata: Are you hungry?

Brian Watt in scene: You know what? I’m okay. I might get hungry.

Jo Takata: I’ll get you something later.

Jo Takata: I’m a longtime resident of Alameda, 81 years, although I was born in an internment camp, as Kent was, but we came back here. I was a history teacher at Alameda High.

Kent Takeda: I’m Kent Takeda. I’m 80. There were six kids, three were born in Topaz, Utah, the incarceration camp that the people in the Bay Area went to. I was born in 1945.

Brian Watt: They’d also invited a local historian they’ve become friends with.

James McGee: I’m James McGee, former resident of Alameda, and I live down in Fremont now. I’m a full-time teacher, 37th year, and I’ve always loved history.

Brian Watt: All three of these folks are connected through their fascination with the history of the island’s Japanese American baseball scene. James has researched and written about the Alameda Taiiku Kai baseball team.

Jo Takata has been determined to document the struggles of her elders before World War II and the internment camps.

She says in 1900, there were 110 Japanese people living in Alameda.

By 1910, that number had quadrupled. But life was tough. They faced discrimination, worked as gardeners and houseboys and girls and cleaners.

They made their own shops and businesses and lived near them, making a six-block area around Park and Oak Streets, Alameda’s Japantown.

They started families, had children and that community was anchored by two churches — one Methodist, one Buddhist.

Jo Takata: Part of them went to the Buddhist temple, part of them went to the Methodist church. And the thing they had in common was they didn’t like Japanese school, and they loved baseball, they loved sports, and that’s what brought them together, the two churches. It was baseball.

Brian Watt: James McGee says this burgeoning of baseball was happening in Japanese American communities throughout California.

James McGee: The first generation immigrants from Japan, some of them already knew the game. It was in its formative years in Japan at that time, very rudimentary, and they brought some of that with them to America.

Kent Takeda: And it became kind of a galvanizing, central pastime for them. So it wasn’t just Alameda, but it feels like every community had the same kind of energy and interest around the sport.

Brian Watt: Kent Takeda says the Alameda Taiiku Kai was essentially a combination of teams from the Buddhist Temple and the Methodist Church.

Kent Takeda: They decided they would be better off combining and forming ATK, which allowed them to compete well with the other cities.

They built a grandstand and made a field facing the Oakland Estuary.

Brian Watt: Jo says, this became the place to go on Sunday after church.

Jo Takata: It was the event of the week for all the Japanese in Alameda. The women would go in their Sunday finest, their purses, their hats and everything and picnic baskets and they’d go every Sunday and sit in the stands and watch the teams.

James McGee: It really took off in the late 20s to late 30s.

Brian Watt: Historian James McGee says in the late 1920s, the ATK team fielded several strong players, including legendary shortstop and batter Sai Towata, who had been a real leader on the Alameda High School baseball team.

James McGee: Sai was an incredible baseball player. He was captain of the team in 1924 in the spring, Alameda High School Hornets, and he was very successful, very well-liked. And even though he was the best player on the team and the team captain, two other players, Dick Bartel and Johnny Vergis, were offered Major League Baseball contracts, and sadly, Sai wasn’t, because of his heritage, because of his race, it appears.

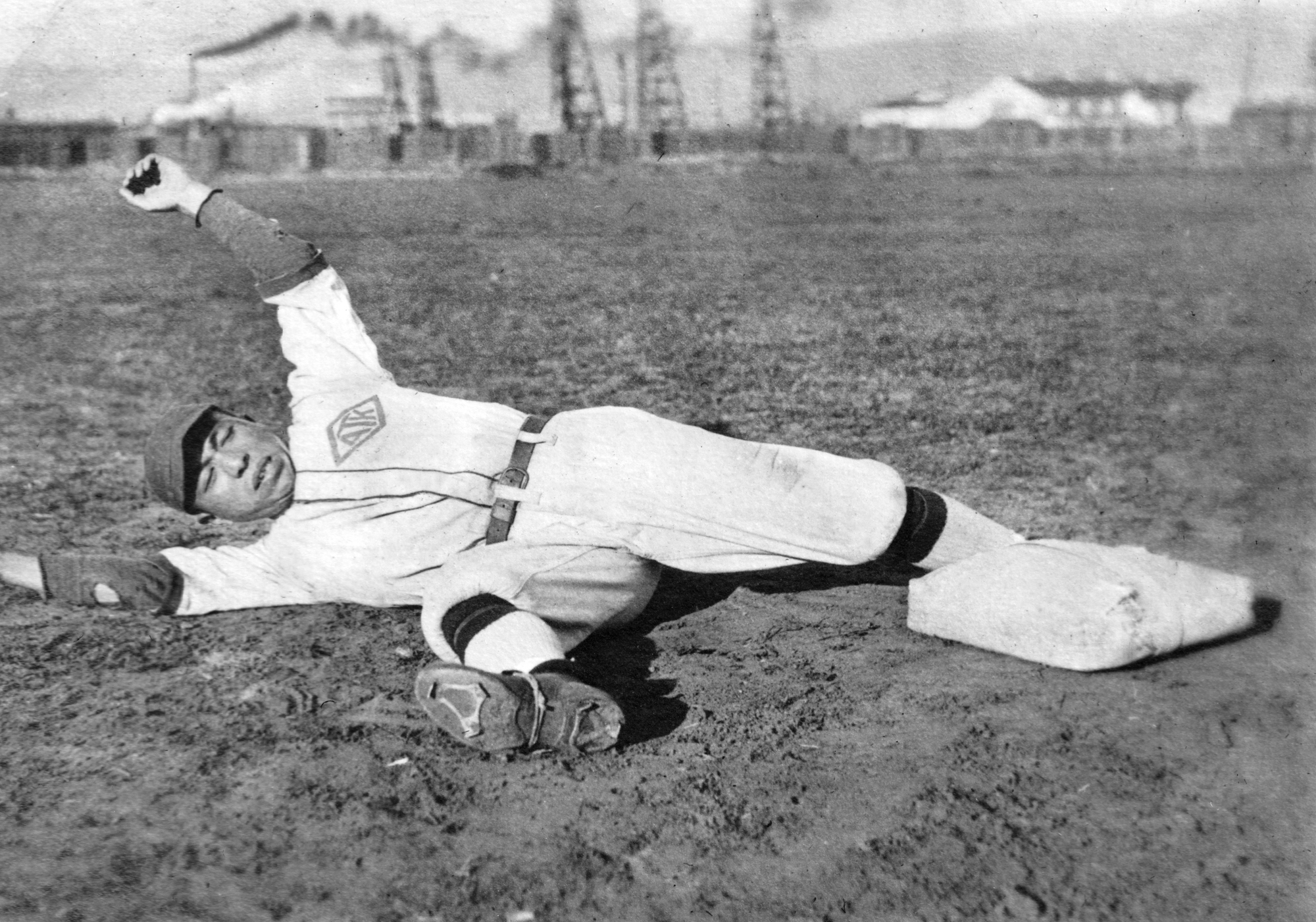

Brian Watt: But Sai Towata would become a star for the ATK team. He was not a big man, but his very efficient bat had a reputation. In one game, he went to bat 5 times, hit a triple and three singles.

Kent Takeda: Sai Towata was clutch!

Brian Watt: Kent Takeda has read about him in old sports box scores and game summaries.

Kent Takeda: Sai Towata was clutch! Clutch. Game on the line, make the big hit, make a good play. Clutch.

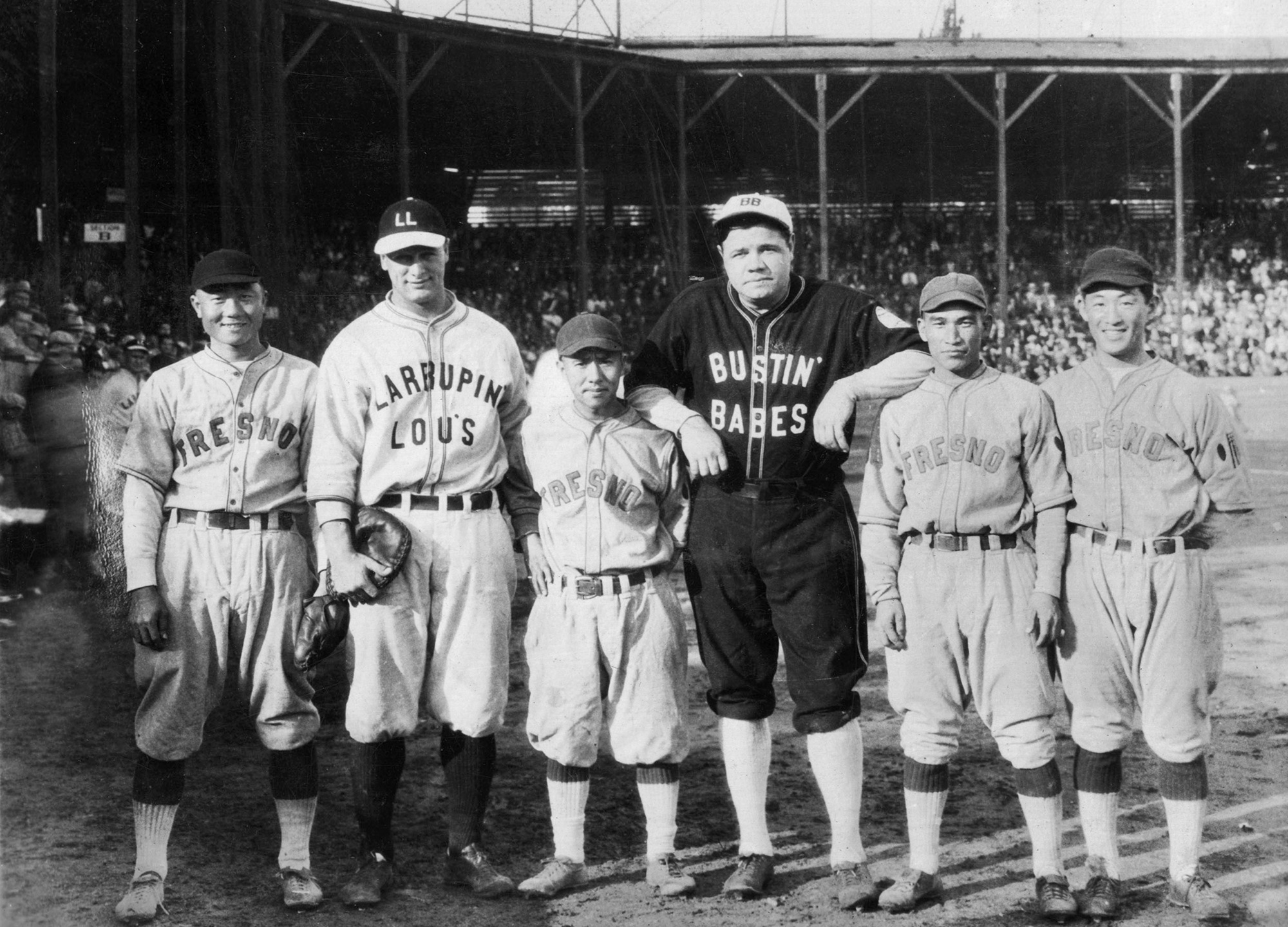

Brian Watt: And, though he couldn’t play in the majors, he joined a Goodwill tour to promote baseball in Korea and Japan that connected with another tour that featured Major Leaguers Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig.

Baseball exchanges between Japan and America became a thing in the 1920s and 30s, with teams traveling to and from both countries. Again, Kent Takeda.

Kent Takeda: So, one year they came here, the next year… My father-in-law, Nobi Matsumoto, terrific ball player, but also strong leader and manager, he also took a team to Japan. I think in mid-20s out of Lodi and Stockton.

Brian Watt: In 1939, any positive exchange between the U.S. and Japan stopped.

Archival newsreel: The United States of America was suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces of the Empire of Japan.

Brian Watt: World War II started, and Japanese Americans would be sent to prison camps, like the one siblings Jo and Kent were born in.

Documentary footage: And now we’re here at the Topaz, Utah relocation center in the desert of Utah. And rows and rows of barracks.

But in the camps, some grown-ups were determined to keep playing baseball. James McGee says, the brother of Sai Towata, John, took the lead in organizing baseball games in Topaz, his camp.

James McGee: In my estimation, it proved to a lot of people, for once and for all, hopefully, that they were American just as much as anybody else, because they had enough moxie and enough bravery to continue on with their American traditions, even if they were behind barbed wire and in a prison.

Brian Watt: When World War II ended and the internment camps shut down, the Japanese Americans were focused on rebuilding the communities they’d been forced to leave.

Kent says John Towata’s organizational skills served him well.

Kent Takeda: He was a good businessman, politically astute in the community of Alameda.

Brian Watt in scene: This is John Towata?

Kent Takeda: Yeah.

Kent Takeda: He gave Jo and I our first jobs. We learned about working hard, or at least making it look like you were always busy, because you had to always be busy.

Brian Watt in scene: And where were those jobs?

Kent Takeda: At the flower shop. Towata Flower Shop.

Brian Watt: The Towata Flower Shop, by the way, became an institution in Alameda, thriving from the years after World War II until it closed in 2009.

John Tawata and other prominent Japanese American businessmen on the island weren’t about to let baseball die after all they’d been through.

The ATK team had disbanded, its players past their prime by the time the war ended, so youth leagues became the thing, with businesses like Towata’s sponsoring teams. And Sai Towata became a coach.

Kent Takeda: He was all baseball.

Brian Watt: He coached Kent Takeda as a boy in the mid-1950s.

Kent Takeda: He was all baseball. He was one of the kindest, soft-spoken, gentle people. You know, you have a sense of coaches being competitive, fiery, win for the Gipper, whatever you want to call it, but no, he was just very low-key. He was a good teacher and most of us learned to love the game from the way he coached and he did a lot by example.

Jo Takata: You would never know that he could swing that bat. He never even would say that he was a baseball star. We would have to bring it out of him.

Brian Watt: Jo Takata says a lot had to be “brought out” of her elders. The good memories and the bad. She spent time with their seniors group and remembers Sai Towata modestly celebrating his 89th or 90th birthday in 1992, the day after the plaque marking the ATK baseball field was dedicated.

Jo Takata: Where the plaque is, is where the home base was. That spot meant so much to these men. It was a time for them to shine. Not just shine watching the baseball, but bringing their picnics, they had contests, they had races. It was the event of the week for all the Japanese in Alameda. And the guys loved it because it was the camaraderie.

Brian Watt: And despite all that came after ATK’s heyday — the war, the camps, working so hard to rebuild and move on — Jo says that baseball team will always represent a special moment in this community.

Music plays

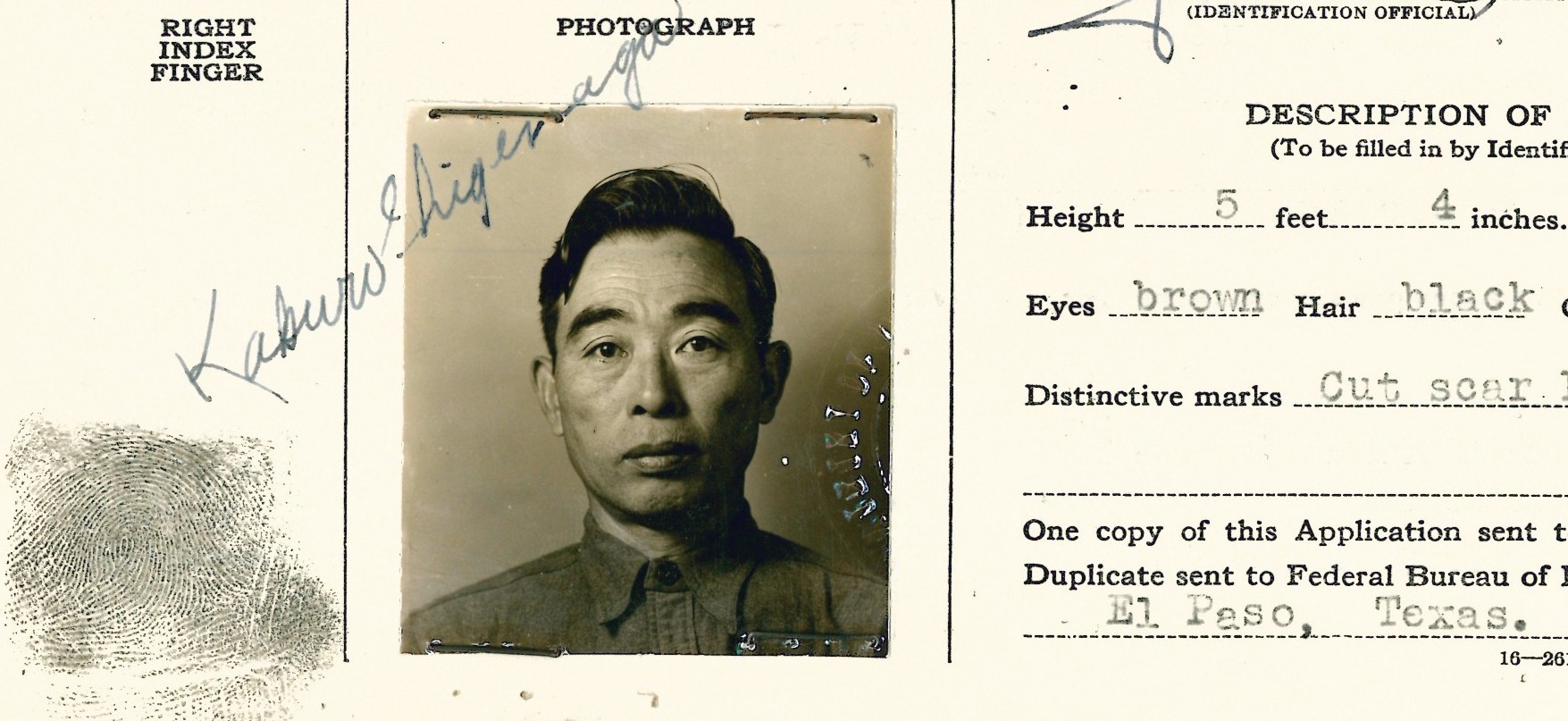

Katrina Schwartz: That was KQED morning news anchor Brian Watt. There are some pretty amazing old photographs of the ATK team and those goodwill tours in Japan and Korea when Japanese American players met Babe Ruth. Head over to kqed.org/baycurious to check those out.

Thanks to Sam Hopkins for asking this week’s question. Remember, if you’ve got something you’ve been wondering about, you can always submit it on our website, kqed.org/bay curious.

Bay Curious is produced in San Francisco at member-supported KQED.

Our show is made by Gabriela Glueck, Christopher Beale and me, Katrina Schwartz.

With extra support from Alana Walker, Maha Sanad, Katie Springer, Jen Chien, Holly Kernan and everyone at team KQED.

Some members of the KQED podcast team are represented by the Screen Actors Guild, American Federation of Television and Radio Artists. San Francisco Northern California Local.

The Bay Curious team will be off next week for the Fourth of July, but we’ll see you back here on July 10th with a brand new episode. I hope you all have a great holiday. Thanks for listening!