Episode Transcript

This is a computer-generated transcript. While our team has reviewed it, there may be errors.

Quinn: My name is Quinn. I’m a recording artist as well as a producer. Uh. Shit. Yeah.

Morgan Sung: Quinn is just 20, but she’s been making music since she was little.

Quinn: I started producing at nine on my mother’s iPad. And then when I was like 12, I started sharing music on fucking uh BandLab.

Morgan Sung: The world seemed to come to a standstill when the pandemic hit in 2020, but that’s when Quinn really threw herself into music. She would stay up all night talking to other producers on Discord.

Quinn: Bro that shit was so fun that it like fried my dopamine receptors. Just had nothing but time on our hands, was making music, going crazy on the music. We used to do stuff like beat battles where we all get a sample and we try to flip it in 30 minutes and whoever, you know, whoop-de-woop, wins. No real reward in it. Just see whoever like has the most talent or whatever.

Morgan Sung: At 15 years old, Quinn had amassed a sizable underground fan base. Then in late 2020, her music blew up.

Quinn: If you hop in, fly G, post it on my watch list, say that you’re invincible, okay ni*** watch this, one phone call

Quinn: I woke up for school one morning and I saw it in my Twitter notifications that like somebody just reposted like a screenshot of the Spotify playlist and it had a picture of me. I ain’t gonna lie, when I initially saw it I was just like, oh that’s cool.

Morgan Sung: Her photo and music had been featured on Spotify’s official “hyperpop” playlist, a platform that wound up launching careers and shaping an entire genre.

Quinn: Like I was kind of just the face of it for a while, along with other artists as well. But they just kept putting me back on the cover and I was just like, shit. Like now everybody wanted to be on the hyperpop playlist. Like once they saw one person did it and that was possible, everybody knew it was possible, which I felt amazing about. Like if you got called a hyperpop artist, like people was getting living wages from having two, three tracks on the playlist.

Morgan Sung: So, the term “hyperpop” suddenly became a big deal. But no one really knew what it meant. It seemed like any vaguely electronic music with angsty lyrics could be called “hyperpop.”

Quinn: The scene that I came from has existed long before me. And for a while, nobody knew what to put a title to it. Like they didn’t know what the fuck to call it. They, so they just called everything like “hyperpop”. They called it, they called underground rap “hyperpop”. They called drum and bass “hyperpop”. They called just any regular house, club, anything that’s fast paced, they called it “hyperpop”. And I didn’t really see it to be a viable umbrella term, because some of this shit is not “hyper” and it’s definitely not “pop” but I’d say hyperpop was more of like a tool of of branding than a uh than a genre title.

Morgan Sung: This is what Spotify has become notorious for, identifying emerging music scenes, calling them microgenres, and slapping on labels before the community making that kind of music has time to decide what to call itself. Artists themselves often don’t know what the labels mean.

Quinn: Spotify was definitely king of buzzwords for a fucking minute, like just making bullshit. Oh my God. I can’t even remember half of the names they came up with. Oh yeah, they call it certain songs like “hood trap” and shit. That one just feels racially motivated, bro.

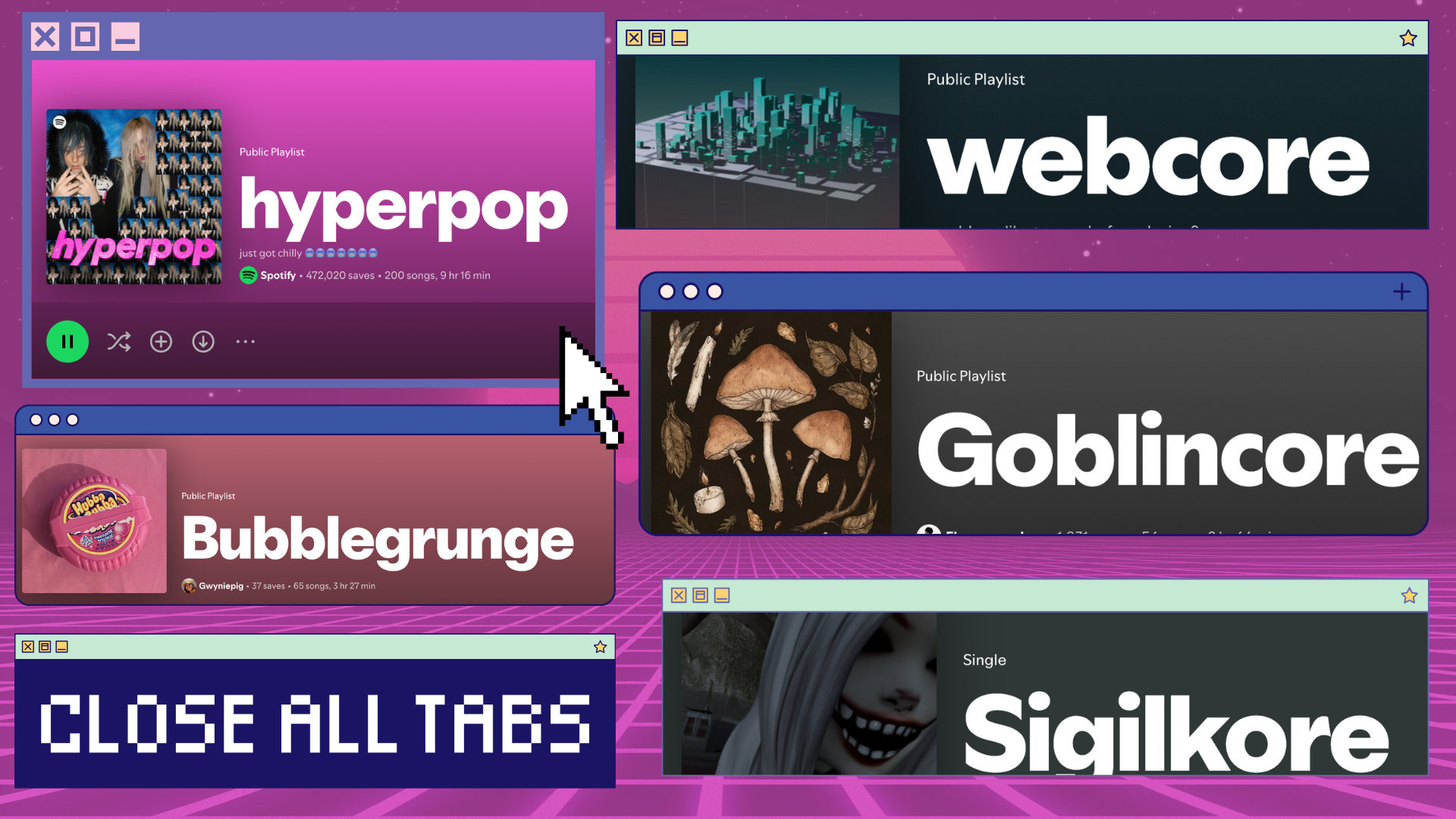

Morgan Sung: Bed Rotting. Goblin Core. Anime Drill. Lo-Fi Jazz Hop. Pink Pilates Strut Pop. Mellow Gold. And my personal favorite, Bubble Grunge. And there are thousands more. But beyond the absurd names, Quinn says this practice is actually problematic for artists.

Quinn: You know, they affect artists bad because here’s the thing, here’s what happens, they drop a playlist and they’re putting all these artists into that playlist and it’s like this new ass genre name, like no one’s ever heard of this shit before. It’s like, what the hell? So, sometimes that creates competition. Like, say you got a genre like, I don’t know, fucking, they call it “proto-country” or some shit. You’re gonna get a whole bunch of country artists who have, they don’t even know what that’s supposed to sound like, but they’re getting put into this playlist.

And it’s like, bro, like they’ve seen a lot of streams from it because it’s a Spotify official playlist and everything. So things get competitive. And then that’s why everybody be like, yo, you know what? I’m the creator of this shit. Like, nah, I created this shit so now you just have an ongoing feud forever. And now it’s always competitive. And you got this genre that didn’t even get to flourish on its own without an audience to have an opinion on it. So it’s, like, damn, bruh. I think that’s what happened with hyperpop.

Morgan Sung: Quinn actually doesn’t consider herself a “hyperpop artist”. She released some hyperpop music after blowing up, but since then, her sound has evolved drastically. She said that the popularity of the playlist pressures artists to continue creating the same music in order to continue getting playlisted.

Quinn: Most days I see that shit and I’m like, bro, I blew up way too early because that shit has set a crazy standard. It’s sitting at 20 million and what? Like I just I’m not I don’t know how I’m supposed to surpass 20 million streams. Well, I know how am supposed to. It just doesn’t feel very realistic. So it’s set a crazy standard for me.

Morgan Sung: Listeners might only learn about emerging music scenes from Spotify’s microgenre playlist. But where do these microgenres even come from? And are they accurate representations of these music communities? This is Close All Tabs. I’m Morgan Sung, tech journalist, and your chronically online friend, here to open as many browser tabs as it takes to help you understand how the digital world affects our real lives. Let’s get into it.

Morgan Sung: Time for a new tab. Every Noise At Once.

Before we get deeper into microgenres, we need to talk about how Spotify came up with them in the first place. And my friend Kieran is going to help explain it all.

Kieran Press-Reynolds: Hey, I’m Kieran Press-Reynolds. I’m a writer at Pitchfork and other places. I write about the internet and the intersection of technology and music and like microgenres, TikTok trends, kind of all the digital detritus and genius happening online.

Morgan Sung: It all started back in 2013 with this project called “Every Noise at Once”.

Kieran Press-Reynolds: So there’s this guy, this like programmer and kind of genius in a way named Glenn McDonald, who had this sort of like genre discovering algorithm. It would scrape the internet and different platforms and basically map out like the entire musical world.

Morgan Sung: He put it all online, and the website featured this massive, color-coded scatterplot, a word map of music from around the internet. Instead of dots, it had genre names that you could click on, and it would play an example. And there were subgenres within each genre. The whole thing was arranged to show how each genre relates to others on the map.

So, in the words of Glenn MacDonald, the bottom of the map is more “organic”. You have genres like “dutch baroque”. And toward the top is where it gets more mechanical and electric. That’s where you’ll find genres like “acid core”. In between all that is where it gets really interesting. The left of the map is, quote, “denser and more atmospheric”, whereas the right side is “spikier and bouncier”. So, for example, all the way on the left of a map, you might see a genre like “voidgaze”. But all the way on the right, directly across from Void Gaze, you’ll see something like “Rwandan hip hop”.

Kieran Press-Reynolds: It would like scan text and so it would look at like journalists reports of like what people have called these artists before and it would Look at like sonic attributes like I guess probably like the the tempo or whether something has a certain instrument or like happy or sad sounding music, bright, you know, dark. Um and it would combine all these things into like an equation um and combining that with like regional details and uh maybe even like sort of like similar artists that had been, that had liked that stuff or had been kind of associated with it and it would group it together into an algam.

Morgan Sung: Every Noise at Once was essentially a constantly evolving encyclopedia of music taxonomy. Glenn McDonald created it while working at Echo Nest, the music data firm that Spotify acquired in 2014. After that acquisition, Spotify incorporated Glenn’s genre data mapping into its recommendation features and playlists. He maintained Every Noise At Once on the side, but at Spotify, was in charge of categorizing songs and naming new genres.

Kieran Press-Reynolds: Everything that Glenn would find through every noise at once would become like a Spotify playlist and they would use that data to kind of like map out emerging scenes.

Morgan Sung: Sometimes, the genre names were based on what people in the music industry actually called it. But a lot of times, these hyper-specific, niche microgenres seem to come out of nowhere. Kieran describes finding one randomly one day.

Kieran Press-Reynolds: I just see this playlist called “escape room” and it looks official and I click on it and there’s like a weird image and it says like there’s not really a bio but it’s like “see also other playlists” and there’s like “pulse” and like “drift” and like “isolation chamber” or something and then I google “escape room” and there are other people online also confused like on Reddit. And then I eventually find like an interview with the guy who runs Every Noise At Once talking about it. And he’s basically just like, “yeah, I like made it up”.

Morgan Sung: In a Spotify blog post, Glenn McDonald said “escape room”, quote, “feels connected to trap sonically, although it’s more experimental indie R&B pop that spins off from the sonics of trap.”

Kieran Press-Reynolds: So like five genres just mashed together into nothing. And yeah, he says it’s a silly play on trap, but it reflects something about solving and creating puzzles and music. Dog was just playing around.

Morgan Sung: As a personal project, every noise at once was incredibly cool. In the decade he spent running it, Glenn would update the site with features that tracked music across cities, generations, record labels, you name it. Sometimes the names were silly, but most of the time, the genres were based on real data science. However, Kieran says that when Spotify used that data to optimize their playlist curation, they usually overlooked a lot of the cultural nuances that make up music scenes.

Kieran Press-Reynolds: Well, I think in the first place, it sort of devalues what music and culture is. Like, I mean, Spotify, I think itself is like it’s a tech platform, right? And it’s always trying to chase profit and scale, which comes at the expense of like proper context. And I think Every Noise At Once, what it’s trying to do is basically say that unless you can capture it with data, then it might not be worthy of being called a genre. And like you see this happening with things on the platform where you know, they said unless something gets 1000 streams, then they’re not going to give any of the money to the artist because it’s almost like not, it’s not worthy of being called a song unless people are listening to it.

But there are tons of like cultural scenes and little, you know microcosms of society that aren’t even online and their music, it can’t be grasped by data because it’s not racking up streams in that way. And what happens is that like you can have genre almost like forced into being because it might not have enough streams unless you combine a bunch of artists that aren’t necessarily together into like a made up macro term or a label and Spotify and Every Noise That Once has done this where they’ve kind of forced different musicians together into an umbrella term, so they can sort of say is its own genre.

Morgan Sung: And that’s exactly how Quinn ended up as the face of hyperpop, even if she didn’t consider herself to be a “hyperpop artist”. Spotify’s hyperpop playlist was pretty controversial among musicians. We’ll talk about that after a break.

Morgan Sung: Let’s open a new tab. What happened to hyperpop?

Kieran Press-Reynolds: It is so funny because hyperpop is like the thing where like, I’ll email my dad and be like, listen to this song and he’ll be like, “this is absolute rubbish. Like, what are you listening to?” You know? And it’s like, it is like this stuff that will kill a Victorian child.

Morgan Sung: Before hyperpop there was

Kieran Press-Reynolds: “PC music”.

PC music in the early 2010s was like this British collective of like, uh, A.G. Cook, Sophie, Hannah Diamond, these various like experimental singers and producers whose whole thing was sort of like pushing pop to an almost like farcical, like ridiculous extent. And built into it were like critiques of capitalism and almost this like accelerationist desire to push capitalism so far that it’s like it’s a parody of itself um and so you’d have like robotic voices just like so glittery it’s like deliciously sugary music. And so it did really like stand for something and there was like a hyper energy to it and they were really influential and inspired a lot of newer gen people.

Morgan Sung: This newer generation of musicians took a lot of influence from PC music, but also from other genres too. Some took more of an emo or punk approach, while others leaned into lo-fi beats and rap, or they blended all of it together. Many of these artists making this kind of surreal experimental music were trans and formed collectives online.

Morgan Sung: As these online communities grew and amassed listeners, Spotify noticed. And by 2019, the platform had enough data to justify calling it a genre. They launched a sprawling playlist of artists who made some form of electronic music and gave it a name.

Kieran Press-Reynolds: Yeah, I think hyperpop is one of the most fascinating examples of how Spotify has impacted and sort of rewired the culture. And it’s something that I hear a lot in public, even among like my friends who are very tapped in, they’ll be like, “well, hyperpop was invented by Spotify”. And I’m like, no, like you’re falling for the the slander! It’s really so, hyperpop, it has been going on for like a decade and a half at this point, like, and people were using the term but it got to a thing where I think Every Noise At Once could see the data that there were artists that were big enough to qualify to become a genre on Spotify.

And so in the early stages of it, which was, I believe like 2019 and 2020, it became this almost like community hub because simultaneously while Spotify is sort of sucking up power in the music industry. Journalism is falling apart and there are less and less young people who are writing about these emerging scenes. And so in the absence of like somebody who’s gonna explain what hyperpop is and provided the proper context, Spotify’s playlist became the first thing that would show up when you Googled “hyperpop”. And so for a lot of people who are discovering it during the pandemic, it became the like guiding light, like the tour guide for what this thing is.

Morgan Sung: This is why Quinn described hyperpop more as branding than as a genre. Over time, the playlist started to define the genre instead of the other way around.

Kieran Press-Reynolds: A lot of the artists who were in it and some of whom were being put on the playlist were very young people and so this was like their first kind of like chance at being known and a lot of them, their like livelihood became based on whether or not they were, they had a song included on it because the royalty boost they would get would like pay their rent. And then simultaneously there were so many sort of like interscene feuds because Spotify would let various people take over the playlist for a month, and then one month, A.G. Cook, the godfather of PC music took it over and basically put in a ton of music that people thought was not hyperpop at all and was less of this grassroots, like DIY, queer, trans stuff that had kind of invented the genre and more just like random famous musicians.

Morgan Sung: So those smaller DIY artists lost a lot of streaming revenue once they were removed from the playlist.

Kieran Press-Reynolds: And it eventually made it so that a bunch of different artists who made like rap and who made pop and who made internet-y music were just all consolidated into this hazy blur of a label, and it got to the point where it’s really sad but like people just didn’t want to identify as hyperpop anymore because of how stained and polluted the label was even though i think hyperpop is a good term and it predated the playlist now for a lot of people it’s like hopelessly contaminated thanks to Spotify.

For a lot of them, artists like Quinn, who at one point told me she felt like the trans, POC origins was being whitewashed out of hyperpop. I think those people felt this sort of sickness toward hyperpop and sort of seeing their impact be erased.

One of my big things is I don’t think playlists are necessarily evil and I think you can put a lot of heart and thought into them, but I think, you look at other platforms like Tidal where they have like an editorial arm where they can like provide context for choices and like Spotify is a massive company and you know all you have to do is like get a writer or two to like research and explain what the history of hyperpop is and like what PC Music did — their impact — and I think what has happened is because of how important the hyperpop playlist is and because of industry heads have sort of like used that as the one tool for like what’s popping, it’s created this feedback loop where newer people and industry plants are told to make music like this because it’s the hyperpop playlist and we want to make a trendy sound. And so it has this watered down effect.

Morgan Sung: Hyperpop is just one example of the way that Spotify’s playlists have changed the sound and meaning of a genre. In this case, hyperpop existed well before Spotify named it. But what happens when the platform creates an entirely new genre? How does that impact the way listeners connect to artists? Let’s talk about that in a new tab. Spotify’s micro-genre problem. Let’s go through a few different micro-genres that have popped up on Spotify in recent years. So a couple of years ago, Kieran stumbled across a Spotify playlist called Webcore.

Kieran Press-Reynolds: Oh gosh, I don’t know — it doesn’t sound like anything because it’s not real.

Morgan Sung: Webcore is a visual style that people usually use to describe digital life in the early 2000s. It’s nostalgic for a simpler version of the internet. Think of the Windows XP background with the rolling green hills and bright blue sky. Or picture early blog posts: pixelated clip art, basic HTML layouts, and gaudy Microsoft Word art and clashing colors. When webcore gained popularity as a design choice, Spotify launched a webcore playlist.

Kieran Press-Reynolds: And it was essentially this random assemblage of vaguely electronic, vaguely digital, uh, songs that came from just completely different time periods and genres. There was like Meat Computer who does digicore rap. There’s Aphex Twin, IDM from the nineties, Temperex, which is like urban outfitters, dream pop, like stuff that really has no business being next to each other. And they had this playlist. And my theory is that they just saw that this was a buzzword on like TikTok and Pinterest, because it’s like, it’s essentially like a viral mood board, like cottagecore or, you know, dark academia.

Morgan Sung: Cottagecore and dark academia are aesthetics that both blew up on TikTok. They refer to fashion and lifestyle choices more than music. Cottagecore is this pastoral fantasy. It’s usually used to describe milkmaid dresses and gardening. Dark academia revolves around classic literature and higher education. It’s inspired by Gothic architecture, collegiate tweed blazers, and melancholic books. Again, not really anything to do with music. But Spotify has playlists for cottagecore, dark academia, and pretty much every subculture you can think of, just like webcore.

Kieran Press-Reynolds: It’s just like a very blurry, uh, collage of vibes and Spotify made this, they hand curated this playlist, um, that had no information about what it was. It was just like, a picture and the tagline was like, would you like to save before closing, or something, and then these songs. And it got really big, really fast. People were saving it and I noticed on Twitter that people were starting to talk about webcore as a genre. They were like, “I love this webcore song.” And I’m just like, “This is not real. This is, you know, this a psyop.” And I think it really illustrated Spotify’s power, like in this sort of dearth of real journalism happening, like people look to Spotify as like “the guide.” It wants to capture every single audience possible. And also capture specific audiences, hyperspecific ones, so it can feed them back hyper-specific targeted ads, feed them, back its own version of the culture, which it can then better market. It feels to me like an attempt to create culture where there isn’t.

Morgan Sung: There are organically made micro-genres that are defined by their visual aesthetic as much as their sound. Like “vaporwave,” which emerged in the early 2010s. It takes dance music from the 80s and 90s, strips it back, and reworks it into a slower, heavily synthesized version. And visually, it takes a lot of inspiration from the neon pink and purple motifs that were popular back then. But like the music itself, it’s distorted and reworked.

Kieran Press-Reynolds: That was a real scene. That was the community. That was musicians and visual artists who thought they were making something really new and weird. And they really identified with that world and trying to kind of build out lore and like paratext for what they were making. And it’s not even like what Spotify is trying to do with a lot of these things like hyperpop and webcore. It’s not like it really wants to nourish the scene and take care of it. Maybe someone at Spotify would say that, but to me it feels like marketing tags and it feels a way for them to organize data and a way for them make music more intelligible to algorithms so they can feed it to people. There is that, to me, an empathy gap or a meaning, a thought gap in what like vaporwave pioneers were doing. And what Spotify is doing. And I think it’s funny because you could think, I mean, webcore almost sounds like a synonym of vaporwave. And it’s just like the drastically different sort of ideas of what they are, I think, really makes the shallowness of webcore clearer.

Morgan Sung: And Kieran says it’s not just Spotify by itself, but the way that the attention economy and profit drive internet culture today. Like how Spotify’s micro-genres and TikTok virality are deeply intertwined.

Kieran Press-Reynolds: It’s hype cycles, right? It’s like ephemerality. It’s like the way that these platforms, the way they need to function in order to get enough views, get enough people using their platform regularly. They need things to be exciting all the time. And so the way TikTok and the algorithm works, and you can apply this to even other, like to Instagram and to the way that shitpost pages will christen a new rap star every week now. It’s like you need to feel like there are new trends popping constantly. A million genres and nothing sticks, both because people are already moving on to the next one. They’re already tired. And because the artists themselves, there’s no incentive to take a long time anymore. You need to be constantly creating content. The rapid pace of TikTok feeds into Spotify’s system where it’s always recommending you new things, where you always feel like. It’s exciting and new and it creates this like endless feedback cycle.

Morgan Sung: What are the costs of this?

Kieran Press-Reynolds: I mean, like the beautiful power and the beautiful positive of Spotify is that you get everything, right? Everything in the world you can listen to. It’s an endless buffet. And so there’s really it gives you a little reason to like want to venture out of that and to go and actually research music and like why something is the way it is. And so when the platform like puts it into its own little box without any information about it you don’t even like it’s like you lose part of the fundamental the fundamental essence of why music is so great i think which is like the humanity behind it like the community surrounding it like the real life feeling of it.

Morgan Sung: Micro-genres themselves aren’t inherently bad. I actually used to use Every Noise at Once to find new music. But in 2023, Spotify laid off Glenn McDonald and cut off his access to the internal data required to update the site. And earlier this year, he announced that Spotify had switched to tagging genres using machine learning instead of human supervision. So all of those issues we talked about with micro-genres, the lack of nuance and context, they’re even more pronounced now.

As the platform relies more on machine learning than human curators, its playlists are becoming more and more personalized. If you search for micro-genre names now, you’ll probably see something called a “mix.” These are algorithmically generated playlists that are based on your own listening history. My hyperpop mix is full of songs that I’ve already listened to, which aren’t even hyperpop. These personalized mixes are even more divorced from the genre’s origins than the editorial playlists ever were. So how do you break out of the algorithm bubble and find new music? It’s easy to let curiosity atrophy when content is just served to us, but being actively curious about music is the first step.

Kieran Press-Reynolds: They’re very simple ways to like exercise your curiosity. Like I like Spotify’s “fans also like,” that’s like one good feature on the platform. I’ve found cool artists that way. I think I do love like going to the bottom and like user generated playlists. Like they show up on artists profiles. And oftentimes if you go beyond like the first few basic ones, there are some intriguing ones usually that like are kind of like a look into a random person’s taste profile.

Morgan Sung: Quinn says she used to rely on Spotify’s editorial playlists to find new music, until she figured out how to break out of her algorithm bubble.

Quinn: When I find an artist, I go onto their “similar artists” and I listen to their music and so on and so forth. I go on YouTube, I look up any interviews they may have had, because I like to hear artists, I would like to here what their talking voice sound like. I look if they had any sort of performances that I might like, especially if they’re bands. They should turn their YouTube algorithm into a music algorithm, that would greatly help. There’s plenty of YouTubers that are constantly making videos about new genres and new sounds and shit like that. And documentaries as well. Documentaries are fire.

Morgan Sung: And despite her complaints about the platform, Quinn says she has Spotify to thank for launching her career.

Quinn: Honestly, without Spotify, I would not be able to have a living wage off of music, so fire. Awesome. However, pay me more. That’s really just, that’s really the only thing I can think about it.

Morgan Sung: She says that algorithm bubbles are not, AI recommended playlists or not, dedicated music fans will always find a way to explore and discover something new.

Quinn: If you look to these AI models, and if that’s all that is popping up on your shit, then you are probably not, you didn’t go deep enough, you’re not as, you didn’t submerge yourself as much as you want to. And I don’t blame people for that, cause like you said, it’s tough to, to even get to the good shit, you have to get through an army of AI created playlists. I’d say anybody who really wants to search our I don’t think they’d stop at just seeing a bunch of AI playlists.

Morgan Sung: So break out of your algorithm! Okay, now let’s close all these tabs. Close All Tabs is a production of KQED Studios and is reported and hosted by me, Morgan Sung. Our Producer is Maya Cueva. Chris Egusa is our Senior Editor. Jen Chien is KQED’s Director of Podcasts and helps edit the show. Original music and sound design by Chris Egusa. Additional music by APM. Mixing and mastering by Brendan Willard.

Audience engagement support from Maha Sanad and Alana Walker. Katie Sprenger is our Podcast Operations Manager. And Holly Kernan is our Chief Content Officer. Support for this program comes from Birong Hu and supporters of the KQED Studios Fund. Some members of the KQED podcast team are represented by the Screen Actors Guild, American Federation of Television and Radio Artists, San Francisco, Northern California Local.

Keyboard sounds were recorded on my purple and pink dustsilver K84 wired mechanical keyboard with Gateron red switches.

If you have feedback, or a topic you think we should cover, hit us up at CloseAllTabs@KQED.org. Follow us on Instagram @CloseAllTabsPod or drop it on Discord. We’re in the Close All Tabs channel at Discord.gg/KQED. And if you’re enjoying the show, give us a rating on Apple Podcasts or whatever platform you use.

Thanks for listening.