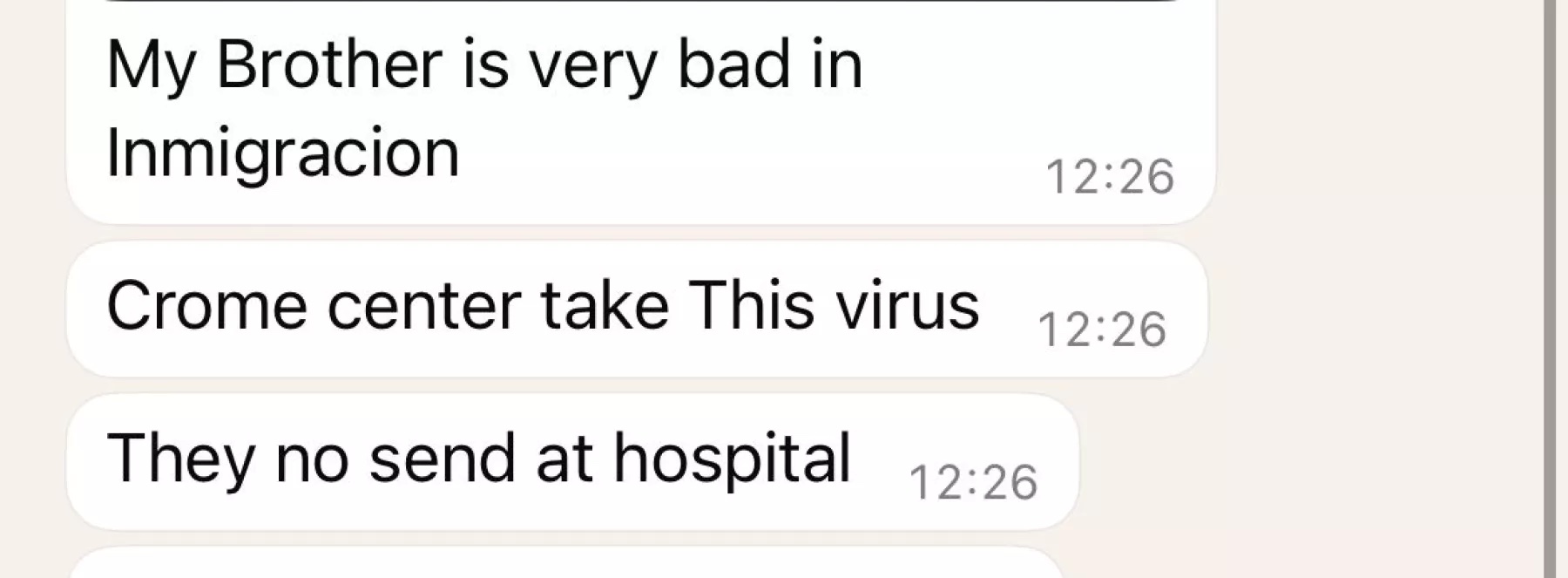

The situation at Krome Detention Center is believed to have gotten so dire, Democratic Rep. Debbie Wasserman-Schultz of Florida paid a surprise visit there last week. She told NPR that in the intake area, two to three dozen men are “crammed into the perimeter of a very tiny room for up to 48 hours. They defecate in front of each other, they eat, they sleep on stone floors. It’s really inhumane.”

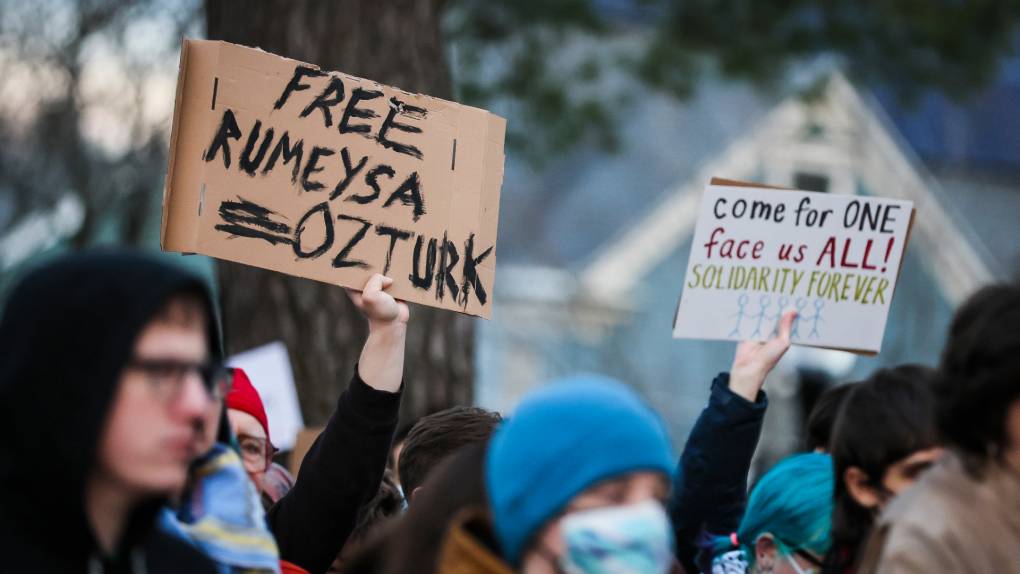

Advocates say this situation is playing out nationally.

“We have seen a rapid deterioration over the last few months,” says Setareh Ghandehari, advocacy director at the nonprofit advocacy group Detention Watch Network. “We’re hearing reports … that there isn’t enough food.” She says she’s increasingly been hearing accounts from people in detention going hungry. “I’ve heard people use the word ‘starving.’ ”

There have been nine deaths in ICE detention since January, which is on track to be the deadliest year since 2020. At least three of those deaths have been in Florida.

Major expansion of detention facilities coming

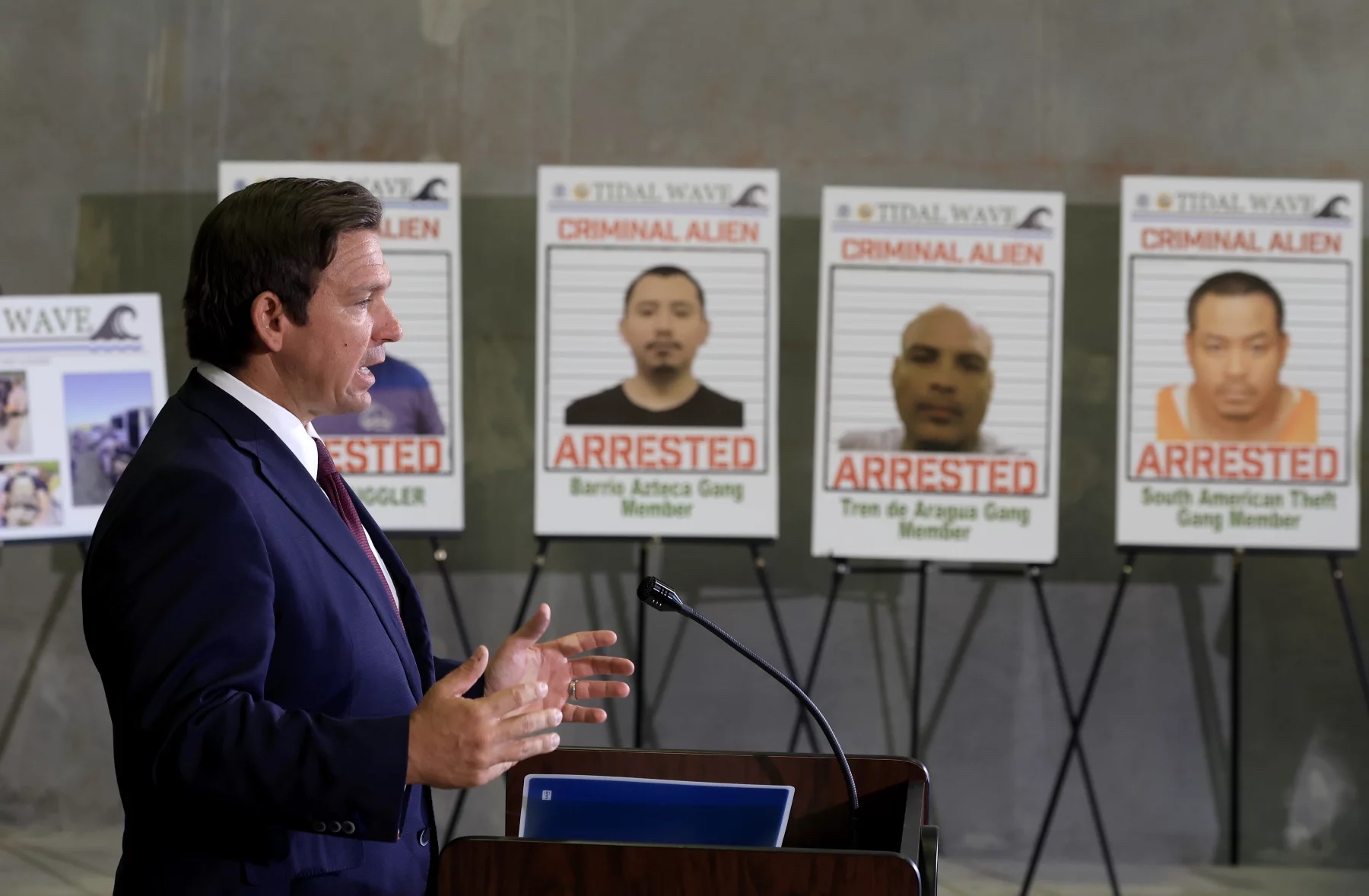

The Trump administration is promising to increase the rate of arrests of immigrants to 3,000 people a day. “President Trump is going to keep pushing to get that number up higher each and every single day,” White House Deputy Chief of Staff Stephen Miller told Fox News last week.

Miller was discussing the sweeping budget bill passed by the House and now before the Senate. It would provide $75 billion over the next couple of years in additional funding for ICE, including $45 billion for detention facilities and $14.4 billion for removal operations.

“We can have, permanently, the safest, strongest, most secure system in American history,” Miller told the network.

But immigrant advocates warn the measure will expand mass detention and surveillance.

“I think that it is not designed to increase the removals of people who are not legally allowed to be here,” says Deborah Fleischaker, former acting chief of staff for ICE during the Biden administration. “It is designed to hold more people for longer.”

Fleischaker believes ICE has historically been underfunded. But she says the bill as written “is so significant and so extreme. What they’re trying to enable … I don’t think it is within the imagination of the American people when they voted for Donald Trump.”

Isacson of WOLA adds that the actions occurring now will multiply. “Plainclothes people using rough tactics and covering their faces to take people off the streets and sort of muscle them into vehicles,” he says. “This is going to be common. And it’s going to become much more common to see that all around the country military bases may have detention facilities.”

‘What are the chances my deportation flight will make a wrong turn?’

“I am anguished. I have not heard anything about my son.”

Late in May, NPR began receiving messages from Vivian Ortega, a mother in Venezuela, regarding her son, Jhonkleiver Ortega.

Jhonkleiver Ortega came to the U.S. three years ago and was working in construction. He was picked up while driving in November 2024 for not having a license, which under Florida state law is not available to immigrants without legal status. She told us she had sold her house in Venezuela to pay for his $7,000 bond in January. When he went to his next court hearing in February, he was detained.

Vivian had heard from him infrequently, and she was terrified “he was barely eating in there.”

Data trackers and policy experts say the Trump administration’s goal of deporting one million migrants a year is so high that encouraging self-deportation is paramount. “The fact that [detention] is often so unsafe and unhealthy leads me to believe that there’s also a desire to wear people down,” says Isacson.

High-profile flights — with migrants sent to the U.S. naval base in Guantanamo, Cuba, and to El Salvador’s notorious detention center CECOT and, more recently, a flight headed to South Sudan — have sent a strong message. For Vivian, the possibility was a source of constant anguish.

On June 3, NPR was able to locate Jhonkleiver Ortega at Glades Detention Center in Florida. He had been to immigration court the day before. NPR was given permission by the family to record his conversation with his mother.

“They told me they had to review my asylum case,” Ortega told his mother. “They told me I have to send proof that I was tortured in Venezuela. And in four months they would give me an answer. And I said I can’t anymore. It’s been months of this. They barely feed us here. I can’t anymore. I asked to be deported. This week or next I will be on a flight to Venezuela. If they give me a call from Louisiana I’ll call you before the flight.”

“What?” his mother asks.

“I asked the judge what are the chances that my flight will get lost and accidentally end up in another country? And she said if that happens you call the deporter. Or email me.”

If you have immigration tips you can contact our tip line, on Whatsapp and Signal: 202-713-6697 or reporter Jasmine Garsd: jgarsd@npr.org