Updated August 5

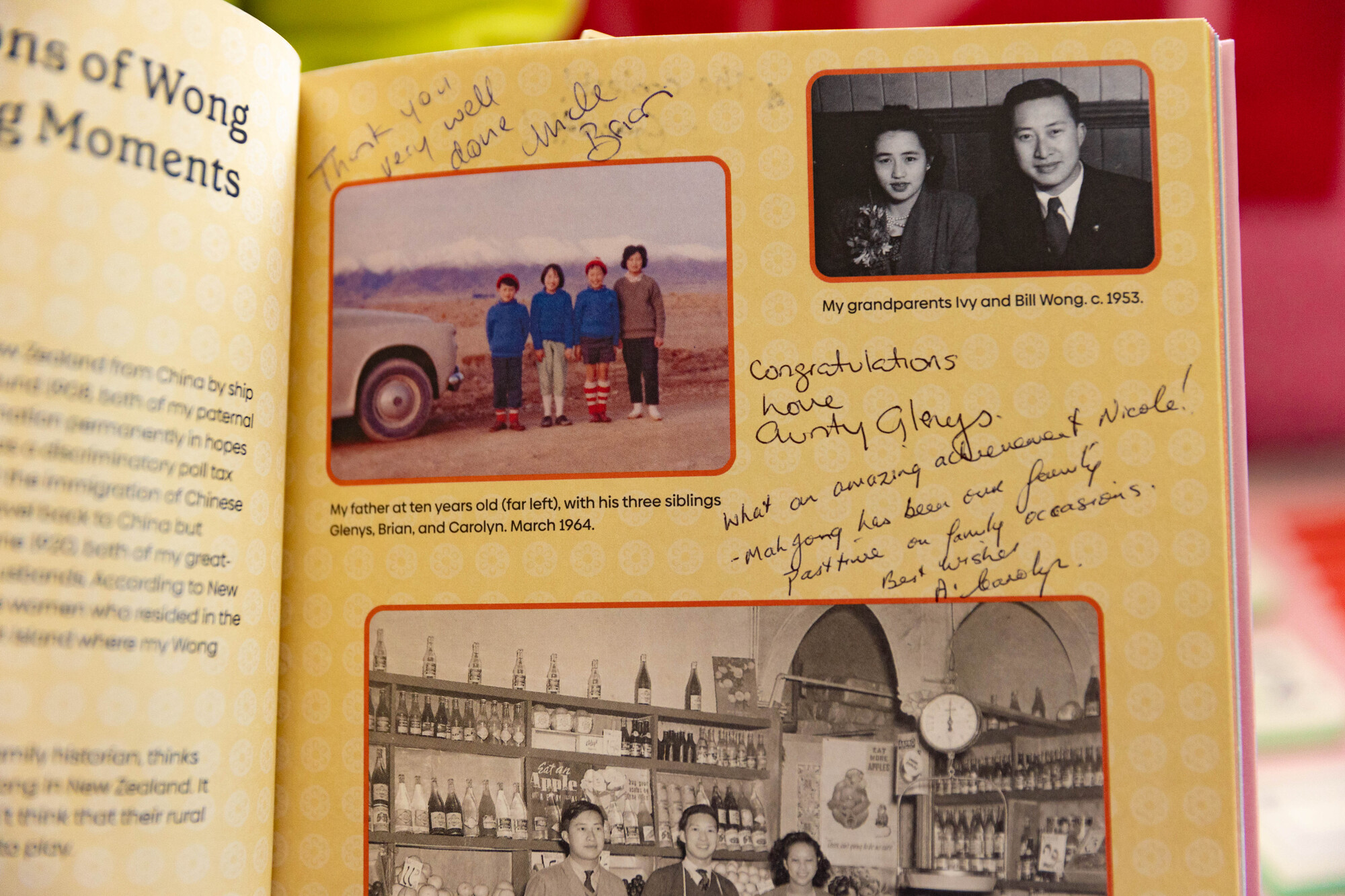

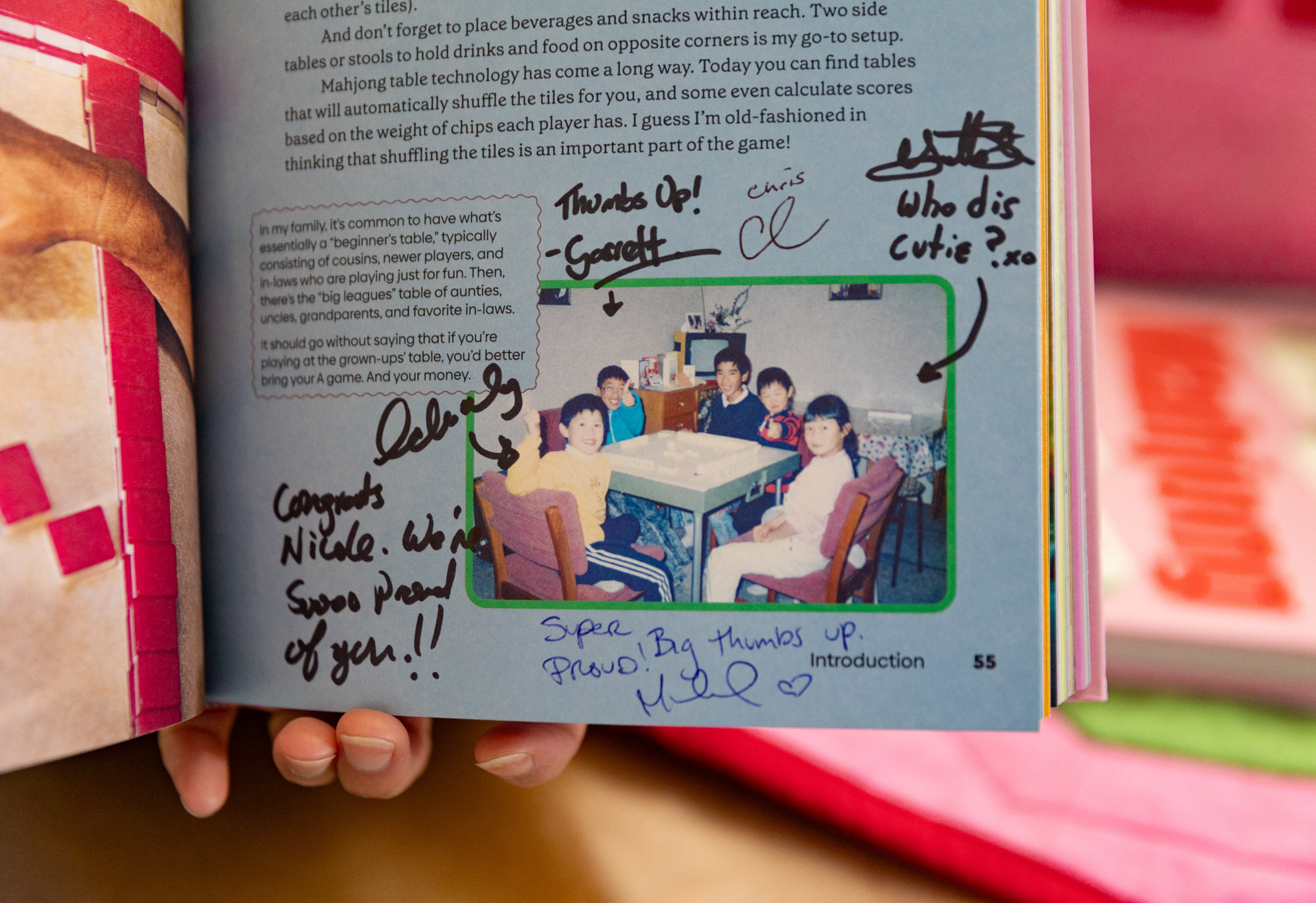

In researching her new book, Oakland resident Nicole Wong interviewed her parents while playing games of Mahjong with them.

“I want to go on the record and say there must have been a time that I’ve beaten them,” Wong said.

Updated August 5

In researching her new book, Oakland resident Nicole Wong interviewed her parents while playing games of Mahjong with them.

“I want to go on the record and say there must have been a time that I’ve beaten them,” Wong said.

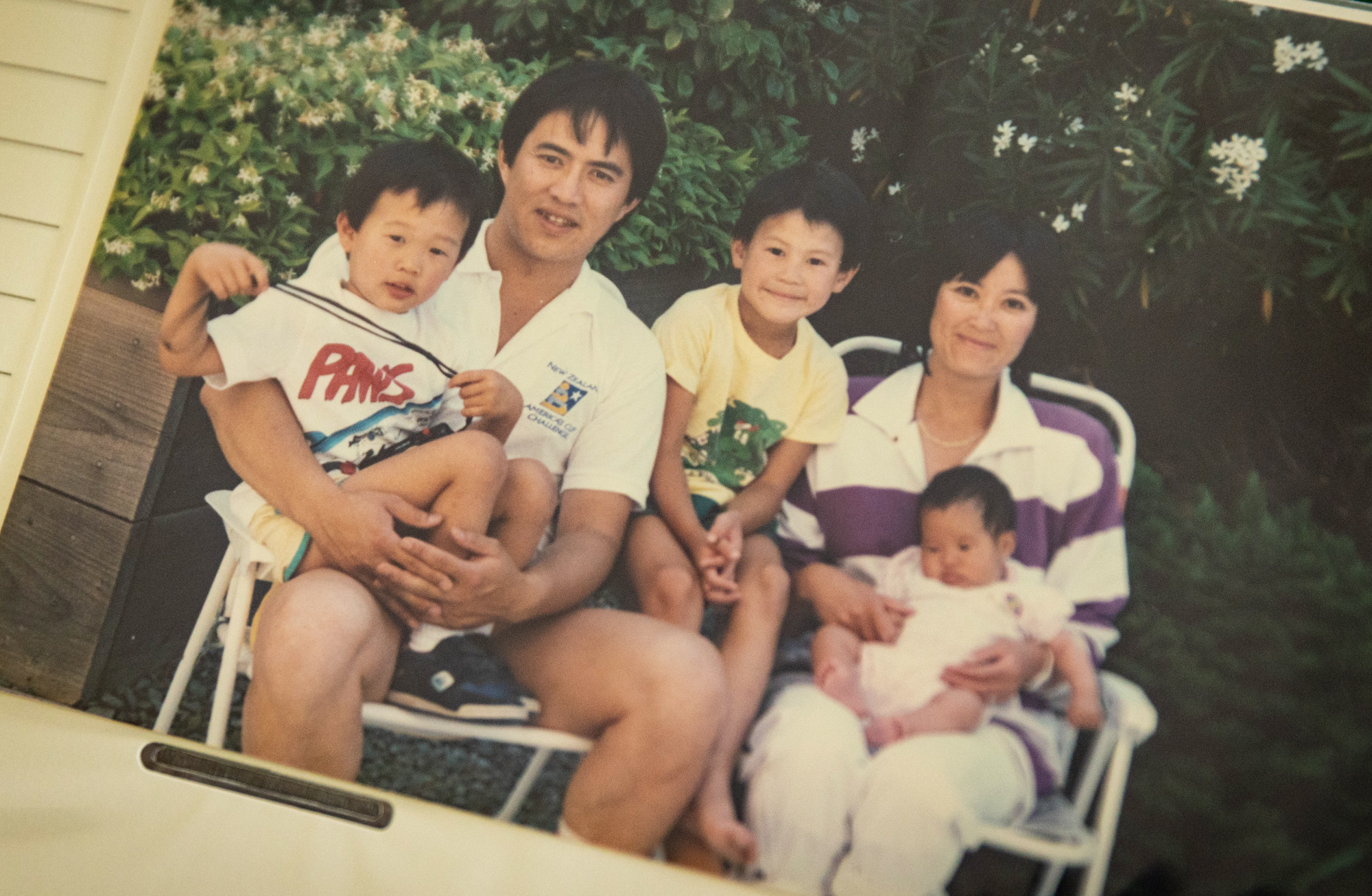

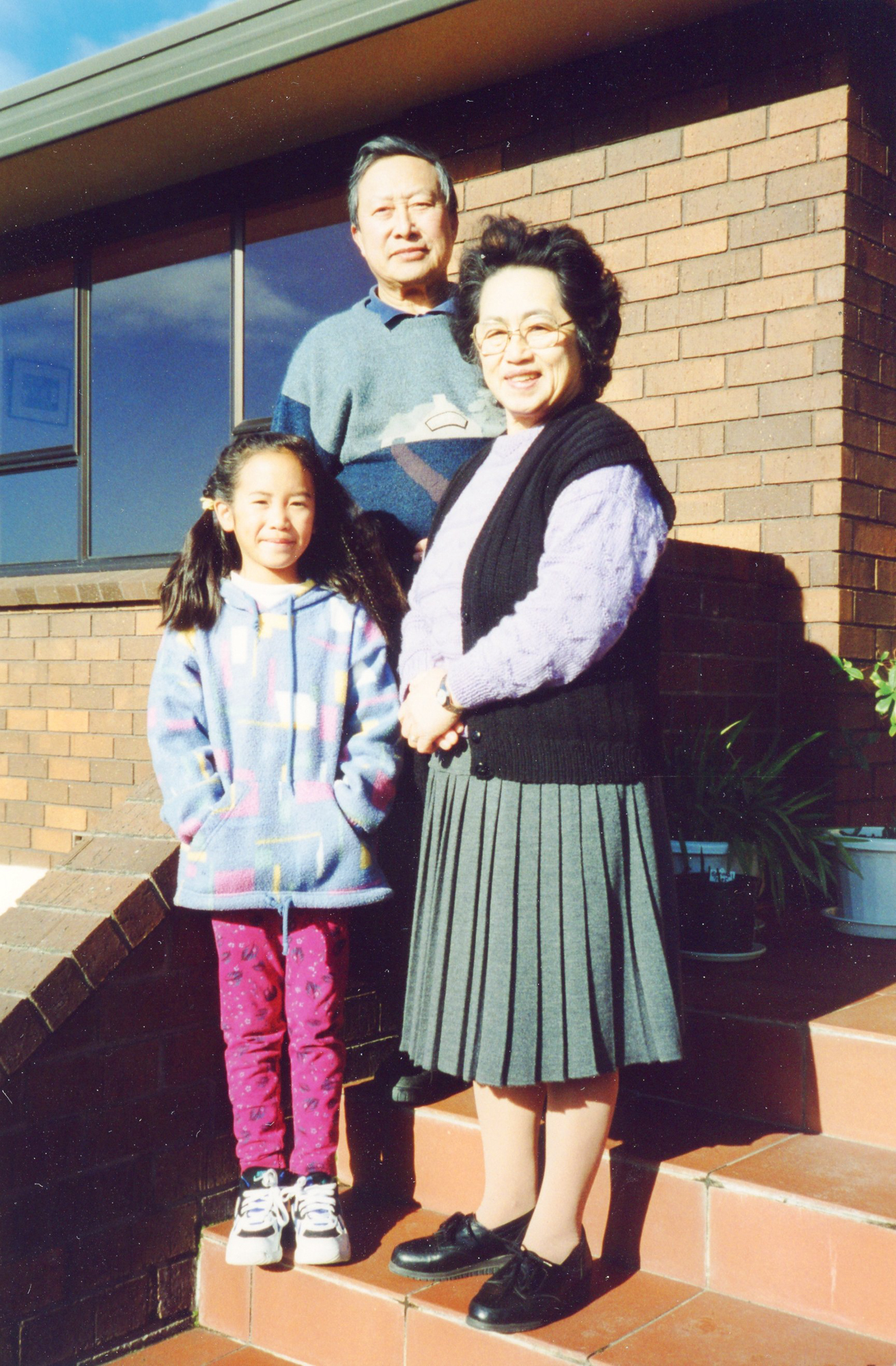

Her website, The Mahjong Project — and later book titled Mahjong: House Rules from Across the Asian Diaspora — originally set out to document the rules that her family played by. And while playing, Wong would pepper her parents with questions: Why did you score this move this way? How do you pronounce this word? How do you spell that? Her parents would pull out vintage Mahjong sets they kept in their closet. Her mother sifted through old photos, recalling the memories behind the images to her.

The stories then expanded to the wider diaspora. Wong spoke to a variety of people — from ages 25 to 80 — about how their family played Mahjong.

“I was playing with a group of people and we all just kind of naturally started talking about family history,” she said. “It’s just fascinating — different parts of Chinese American history just sitting around at the table.”

This interview process ultimately evolved into a form of oral history, the process of preserving original recorded interviews of someone’s personal recollections. This format was particularly fitting for her topic of Mahjong, Wong said, “because the way that most people learn how to play is through oral explanation … Stories about the person who taught you, or who taught the teacher, come out.”

Wong started this project in the role of daughter. But as a new mother herself, she realized she’d become “the person who holds the information now” — and that time was of the essence to capture it from her parents.

“This is a really interesting and valuable time to be talking to that generation above us, where we still can gather those stories,” she said.

Before writing, most knowledge was “through storytelling,” said Roger Eardley-Pryor, an oral historian with UC Berkeley’s Oral History Center at the Bancroft Library. People held their stories in their memories and passed them down intergenerationally, but “once the technology developed in the 20th century to actually record and store those stories, oral history began to evolve more in an academic context,” he said.

If you’re inspired to preserve family memories and community stories this way — whether you want to interview your grandfather, an aunt, a distant cousin or someone else you know — keep reading for expert advice on how to get started.

And if you’re looking for tips on how to preserve family documents and photos instead, take a look at our guide “How to Preserve Your Family History Like an Archivist.”

Menlo Park’s Maggie MarkdaSilva said when people hear how her organization, Narrative Histories, helps record family stories, a common reaction is, “Oh, I am so sorry I didn’t find you before it was too late.”

This is proof that anyone who’s interested should start “sooner rather than later,” she said.

“Don’t worry that you don’t know what you’re doing,” MarkdaSilva said. “Anything you capture is going to be better than nothing [and] be so valuable to you later on, when your parents or grandparents have passed away.”

“It definitely feels intimidating,” Wong, who spent years writing The Mahjong Project, said. “In reality, you just got to start somewhere and start chipping away at it.”

And even if a wider oral history project doesn’t pan out, giving it a shot is also a chance for you to spend time with family members, she said. “It’s been just a really meaningful way to talk to my parents and to my aunts and uncles in a way that has felt really different,” she said.

To get you started, Eardley-Pryor recommended first thinking about the order of family members you want to interview.

“Do you want to start with the oldest person first, in the idea that they might be closer to passing on, and so you want to capture their memories most?” he said. Equally, if you choose to gather stories and questions from younger family members first, “when you interview that elder, you can ask them these things that everyone else in the family is interested in.”

However, you choose to get started, Eardley-Pryor said a good rule of thumb is to see your interviewees as collaborators from the get-go, and make sure you’re on the same page throughout about how the process will look and what you intend to do with the recordings.

“Oral history is both a very ethical process and a product,” Eardley-Pryor said. “The methodology used in it is collaborative. It is shared authority. It is something done in conjunction together.”

“You, of course, would never want to do this against anyone’s will,” MarkdaSilva said — so make sure the person you want to interview actually wants to take part.

That said, many people can initially be hesitant when it comes to being interviewed, she said, with responses like “My life wasn’t that interesting,” or “No one really cares,” or “I’m shy.”

One of MarkdaSilva’s techniques in this case is to bring up young people in the family.

“I have found that once you say, ‘This is for your grandchildren. Could you please just do this for them?’ the elders warm up and they say, ‘Of course I will,’” she said. “Once they begin — oh my gosh, it’s such a great experience for them.”

Eardley-Pryor said you can also sit down with the subject in pre-interviews, like sharing what topics you want to talk about in the recording or look through old photo albums to kick-start memories.

This is also a good place to talk about what the interviewee is comfortable with — and what they don’t want to talk about. He said that oral history allows an interviewee the chance to tell “the stories that they want to tell.”

“Oral history is about deep listening and deep empathy and hearing stories and memories,” he said. “But [also] empowering a narrator to feel like they are in the driver’s seat, because they should be.”

Do your homework, MarkdaSilva said, and “learn as much about the person as you can before you start interviewing.”

In addition to a pre-interview, your research can be about the small details, like finding out what instrument your mom played in her band.

“The more you know already, the more engaging your questions are for the person being interviewed,” she said.

You could also research the historical milestones that took place during their earlier life, the events that “almost everybody remembers,” said MarkdaSilva, like the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. This helps “anchor” the subject’s story and puts it into context, she said.

You want to avoid questions that can be answered with a “yes” or a “no,” said Guneeta Singh Bhalla, executive director of the 1947 Partition Archive in Berkeley.

Singh Bhalla’s organization holds thousands of oral histories in its directory, and she recommends that you “ask questions in an open-ended manner, so that they can answer in their way.”

That said, MarkdaSilva said that some people may be intimidated by very broad questions, so asking a few specific questions can help people latch onto memories they have.

As for where to start, you could ask the interviewee about their grandparents or their oldest family memories, Eardley-Pryor said. These ideas are “a really nice starting point, because it takes the narrator a little bit out of themselves,” he said.

Other good starter questions include:

Some questions to end your interview could include:

In her “how to” section in The Mahjong Project, Wong advises that people should be patient when conducting interviews and give ample space and time for people to respond. Ask questions that “set the scene,” she recommended: “What was it like when? What do you remember from? Use the senses — what did it look like? What did it sound like?”

Be sure to let the subject do most of the talking during the interview and let them lead the interview by not disrupting their stream of consciousness, Wong said.

Your speaker may have a memory that they might not find significant, but is nonetheless a meaningful observation of the time period they’re recalling.

Although you should, of course, be careful not to be too persistent or try to contradict their narrative, these types of follow-up questions will come to you if you stay present and engaged in the interview, MarkdaSilva said.

“If you’re thinking about your grocery list or what you’re going to have for dinner … you need to just stop the interview and come back another time,” she said.

Don’t let following a line of questioning lead you to accidentally push your subject’s boundaries, MarkdaSilva said.

“It’s important to know when to stop because of the importance of rapport and respect,” she said. “There are things people don’t want to talk about.”

The person you are interviewing may have lived through a major historical event or had a traumatic experience. These memories can arise in moments when it’s most unexpected, said Eardley-Pryor, who stressed the importance of outlining what’s on the table for discussion with your subject before starting the recording.

Talking about traumatic memories “require[s] a high level of trust and rapport,” MarkdaSilva said, and should never be a way to open an interview. “Your subject will need to be really comfortable with the process — and with you in this process — before you ask questions like that,” she said. “They’re too personal to just launch into right away.”

Wong said that when interviewees are engaging in another activity, such as playing Mahjong, taking a walk or cooking, she’s seen “those stories kind of [come] out.”

Oral history strategies at the 1947 Partition Archive include not backing off when an interviewee reaches a difficult part of their story. “You don’t want to run away from it and stop talking about it,” Singh Bhalla said, as this can be a potentially healing process for the interviewee.

“Instead, you want to walk them through that moment towards a place of strength,” she said. “You want to focus on how they overcame that, that they’re here today, and how they rebuilt after that difficult thing happened.

“You walk through the emotions, and you come to the other side in a positive and resilient place by talking about the resilience that they demonstrated.”

If you’d like some further reading, KQED has a guide on processing the past with loved ones when discussing potentially traumatic stories.

Give people the chance to take things off the record, MarkdaSilva said. This allows the subject to have “the final say” on what the recording will be, she said. You’ll need to follow through on your word and take the anecdote or section out of the recording.

“You have to be 100% trustworthy,” she said. “So even if they say something that’s really amazing [followed by] ‘No, no, please take that out, I don’t want my progeny to know that,’ you need to take it out.”

While MarkdaSilva acknowledged that others may disagree with this approach, she said she believes “people need to know upfront that their choices about their own personal life will be respected.”

The 1947 Partition Archive provides its interviewees with several privacy options.

“They can choose to keep their story embargoed for 50 years, 25 years,” Singh Bhalla said. “They can choose to make their story only available to research, and they can choose to make their story available only for some types of publications and so on.

“When people have that level of choice, they do trust that we’re trying to keep this in their best interest. We’re giving them agency, essentially.”

Your subject “should always have a chance to review the interview in some way,” Eardley-Pryor said. “Whether that’s listening to the audio again or seeing a transcript of what was the interview recording.”

How to record

The easiest way to record sound is with your smartphone’s default audio app, like the iPhone’s Voice Memo.

But Shanna Farrell, an oral historian with UC Berkeley told KQED Forum that she personally does not advocate for using your iPhone.

One major reason, Farrell said, is security: you just don’t know where those (recordings) are going in the cloud,” she warned.

Another reason is what she called the “instability of the iPhone,” including the possibility of degrading audio quality over long periods of time.

Instead, “I recommend using a handheld audio recorder,” she said. “Some libraries, some historical societies, you might be able to borrow audio equipment from.”

If you want to use a computer or buy a specific recording device, your options will range from the super simple to the very sophisticated, including:

MarkdaSilva said you also use another device as a backup, in case your primary method fails in the moment.

Where to record

“Make sure you’re in a place that’s comfortable for those who are being interviewed — their kitchen table, their living room,” MarkdaSilva said. “Tempting as it is to go to an outdoor cafe or something sort of fun like that, you don’t want ambient noise.”

Extra noise is difficult to edit out of tape, and at worst, it can obscure the subject’s words, so if you’re recording at home, make sure to keep background sounds, like the TV, off.

Transcribing the recording

You can transcribe your recording manually or use software like Otter.ai, Temi, Alice or Trint.

Transcripts can help with searchability, and can also be an opportunity for the subject to re-read the script to correct spellings and names or to retract anecdotes. If the narrator wants to add more information to the transcript, you can include it in the document, although Eardley-Pryor suggested writing it in square brackets to signify something new was included after the recording.

Saving the recording

You can save your recordings on cloud-based options like Google Cloud Storage, Apple’s iCloud, Mega, pCloud, Synology, NextCloud and Plex. Wherever you store items digitally, be sure to come up with an easy-to-follow and descriptive file-naming practice, so you can find documents after some time.

Eardley-Pryor said when starting your project, it’s important to keep in mind that websites — even storage websites and software — may not be around forever, and digital files can also be corrupted or lost over time.

“I would always, always recommend having multiple backups,” he said. “Not just in the cloud, but also having it stored on a hard drive. Or if you have a transcript, having a printed version of them.”

The Library of Congress has a thorough guide detailing the recommended digital formats in which you should save materials. You can also upload files to public sites like the Internet Archive.

Like the 1947 Partition Archives, there are many local and national historical societies and projects that ask people to share their memories and family stories. Local examples include the Bay Area Lesbian Archives, the Oakland Chinatown Oral History Project, the Japanese American Museum of San Jose and the Indigenize Project.

In many institutions, “it’s white men telling the stories of history,” Eardley-Pryor said. But “oral history has this incredible power of allowing people to speak for themselves, to tell their own story in their own words, and to have that be included as a part of the historical record for us to learn from and to shape our future with.”

If you are planning to record an oral history with the explicit intention to eventually donate it, you should establish this with your interviewee at the beginning of the interview and be transparent to make sure they’re comfortable with their story being shared publicly.

You, the interviewee and the organization should also establish other guidelines, Eardley-Pryor said, like:

“You have to respect their answer. You should not donate it if they don’t want it donated,” MarkdaSilva said. “But they might be very flattered. They might be super happy about it.”

Correction: An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated the title of Nicole Wong’s book. It is Mahjong: House Rules from Across the Asian Diaspora.

To learn more about how we use your information, please read our privacy policy.