Episode Transcript

This is a computer-generated transcript. While our team has reviewed it, there may be errors.

Morgan Sung: A quick heads up before we start. This is part two of our deep dive on the government surveillance of protest movements. It’ll make more sense if you start with last week’s episode, which explains how we got here.

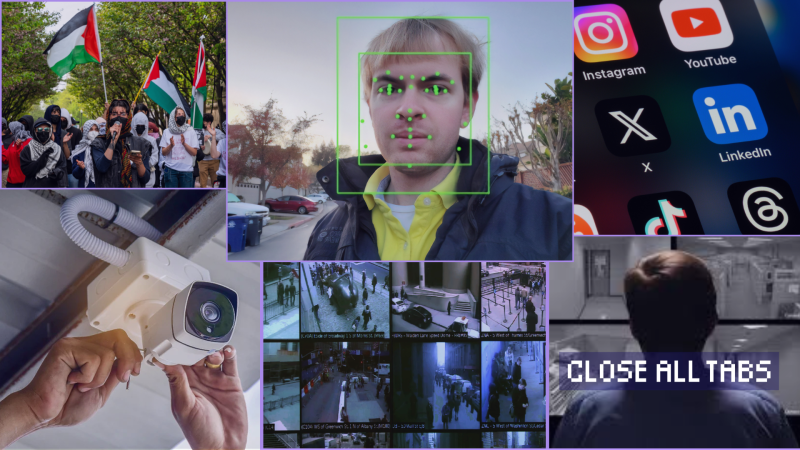

In that episode, we covered the history of American surveillance and how dragnet surveillance became the norm. Dragnet surveillance, if you remember, is where the government tracks everyone, like a giant net scooping up all our information. But what does that look like in practice? What tools are being used to monitor protests? And how does all of this impact our right to free speech? Okay, let’s jump back in.

This is Close All Tabs. I’m Morgan Sung, tech journalist, and your chronically online friend, here to open as many browser tabs as it takes to help you understand how the digital world affects our real lives. Let’s get into it.

Jalsa Drinkard: This was an actual act of digital violence towards our students.

Morgan Sung: Last time, we met Jalsa Drinkard, a student organizer and senior at Columbia University, who served as security during the weeks-long encampment protesting the school’s financial ties with Israel. As the university began cracking down on students through disciplinary actions like expulsions and suspensions, she says many students were caught off guard by the kind of evidence that was presented.

Jalsa Drinkard: A lot of people’s social media accounts were cited at their disciplinary hearings when they were called in to kind of discuss their case. It’s definitely being looked at and collected.

Morgan Sung: In the year since, students who attend protests, or even just express solidarity with Palestinians on social media, have been disciplined or doxed, which means their private information was leaked online. And some now face deportation. It’s a drastic escalation, not only in monitoring what people post, but also in punishing them for it. And that’s raising alarm bells for free speech activists. Though surveillance using social media is now reaching an extreme, it’s been in use for over a decade. Let’s look back at that time and open a new tab. Protests in the 2010s.

Protesters: Don’t shoot! Accountable. Don’t shoot! Held accountable. Don’t shoot!

Morgan Sung: That was from the Black Lives Matter protests in Ferguson, Missouri, after a white police officer shot and killed an unarmed black teenager, Michael Brown, in 2014. And then in 2016, an ACLU investigation revealed that Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram had all shared user data with a company called Geofeedia. That company analyzes social media posts and then groups them by location. Media outlets use the service to spot breaking news stories, and businesses use it for marketing.

But as the ACLU discovered, Geofeedia also marketed this tool to law enforcement agencies as a way to monitor protests. Intelligence agencies had been surveilling and apprehending Black Lives Matter activists as early as 2014. This investigation showed that private companies were also aiding in surveillance. After that ACLU report came out, those social media companies cut off Geofeedia.

This investigation coincided with a period of privacy reform. It was right after Edward Snowden blew the whistle on the NSA’s mass surveillance program. Congress had just passed a new law to curb the government’s mass data collection. And a few years later, the Supreme Court ruled that the government couldn’t go around demanding that companies hand over your data without a warrant. Except there’s a glaring loophole here.

The government can’t demand your data, But there’s nothing stopping them from buying it. And that’s exactly what’s been happening. In the last decade, protest surveillance has become even more intrusive, thanks to this partnership between private tech companies and the government.

News Anchor 1: A controversial social media surveillance tool has been helping the Los Angeles Police Department monitor Gaza protests.

Amnesty International TikTok: Here we are at the end of the route, and as you can see from the map, my face has been scanned every step of the way.

Hampton Law YouTube: These data brokers, they market and sell directly to the government.

Morgan Sung: This is what we’re calling “the surveillance machine,” because it’s not just the government acting alone. Let’s break down how this machine works and how it’s used to target political speech, starting with this: the government is collecting a lot more of your data than you probably realize.

New tab, data as surveillance.

The industry of collecting and selling data is incredibly lucrative. Companies want data for things like credit checks or targeted advertising. This commodification of our personal information is known as surveillance capitalism, a phrase popularized by Harvard professor Shoshana Zuboff. That legal loophole that we talked about earlier, the one where the government partners with private tech companies, it functions because of this system of surveillance capitalism. It’s what allows the government to obtain our data and paint this very detailed picture of us, all without a warrant. It’s all thanks to key players in the system — data brokers. They’re the middlemen. They collect tons of personal information and then they sell it off to whoever can pay, including law enforcement.

Don Bell: It’s like, rather than the police getting a warrant to search your apartment, they just give the landlord an envelope of cash and the landlord lets them into the apartment.

Morgan Sung: This is surveillance policy expert Don Bell.

Don Bell: Now that’s basically the same thing that’s happening with your phone.

Morgan Sung: You know that pop-up you get when you visit a website asking to allow cookies? Or sometimes when you open a new app and it asks for permission to use your location and run in the background? These are all ways that data brokers glean information from your daily commute to what time you exercise to the ads that grab your attention when you’re scrolling in the middle of the night. Each of these pieces of data is a little building block that starts to tell data brokers who you are. Like individual pixels that, eventually, make a full portrait of you and your life.

Don Bell: Large data brokers are able to sell essentially dossiers which contain thousands of data points on any given individual. It could be the doctors that you go to, the places of worship that you go to the protests that you go to, the people that you’re intimate with. It can create this complete picture of who you are, what your beliefs are, what your associations are. And in the hands of a government that aims to surveil and target people, that is extraordinarily dangerous.

Morgan Sung: And the government has used this data broker loophole to surveil groups all over the United States, especially over the last few years. The military, for example, monitored Muslim communities in 2020 by buying location data sourced from a Muslim prayer app. In 2022, ICE got around sanctuary city policies by using information from data brokers to identify and deport undocumented immigrants. One data broker contracted with the government offers a tool called LocateX, which uses location data to track and potentially identify anyone who crossed state lines to visit abortion clinics.

Don Bell: You don’t get that mass surveillance on the scale that we are seeing without some sort of cooperation between ad tech and the private sector and the public sector.

Morgan Sung: After social media companies cut off access for Geofeedia in 2016, countless other companies took its place. One of those was Dataminr, a surveillance company that uses AI to scour social media sites. It’s alerted law enforcement to Black Lives Matter marches, pro-choice rallies, and most recently, protests in solidarity with Gaza. Dataminr often contacted police departments directly, warning them about the precise time and location of protests. These surveillance tools are now being used to punish people for what they say online, a right that’s protected under the First Amendment, specifically our right to free speech. And like we talked about in last week’s episode, the Trump administration is surveilling international students’ social media accounts. Political speech is now grounds for deportation.

ABC News: Tonight, international students at colleges and universities around the country reeling. The federal government revoking a number of visas with little to no warning.

Don Bell: And if you notice that there are people in your class who are effectively disappearing because of their beliefs, you may be far less likely to express your beliefs online. And in doing so, you are seeing the suppression of First Amendment activities.

Morgan Sung: There have been attempts to crack down on data brokers. Some members of Congress are now rallying behind “The Fourth Amendment is Not for Sale Act.” Remember, the Fourth Amendment protects people from, quote, unreasonable searches and seizures, end quote. Their proposed law would ban the government from buying data without a warrant, effectively closing this data broker loophole. It passed the House last year, but it still needs to go through the Senate. And then the president would have to sign it into law. But given the current administration’s recent actions, Don isn’t optimistic that’ll happen.

Don Bell: The thing that worries me enormously is this administration and this national moment is very different from any other moment. If this kind of authoritarian push continues, it’s going to be exceptionally hard to first stop it and then build something that truly protects the constitutional and privacy and civil liberties of all.

Morgan Sung: And here’s the thing with data collection — keeping tabs on our behavior and connections? It’s only one part of the surveillance machine. Even if you ditched your phone and pretty much every other device, your privacy would still be at risk because the moment you step into a public space, your face is being tracked. We’ll get more into that after this break. Let’s get back to the story. New tab, facial recognition for sale.

Nicol Turner Lee: I’m not that old, so I want people to know I did not march in the Civil Rights Movement, right? But I am a student of history when it comes to social movements and civil rights.

Morgan Sung: Dr. Nicol Turner Lee is a senior fellow in governance studies and the director of the Center for Technology Innovation at the Brookings Institution. Dr. Lee researches how technology shapes social justice movements and pointed out that today’s activists are more visible than ever, which means they’re easier to surveil.

Nicol Turner Lee: Back then, the tools that we used, like the telephone, you couldn’t see anybody, right? The telephone tree to tell people to show up in, you know, 25, 25, 35th Street, because we’re gonna march on that day. No one knew who was on the other line of the telephone line. You just knew you were getting a call to show up. But just like today, I just saw on social media, there’s gonna be some protest happening over the weekend, right, and it’s all over social media where it is, who’s showing up. It’s this double-edged sword, like activists do need a space in this burgeoning information economy, but they also need some protection that government, who is supposed to protect our democracy, is not going to use that against them.

Morgan Sung: Social media is fodder for facial recognition technology, which works by analyzing images and matching faces with similar features. The technology is problematic. Studies have shown that it misidentifies black people and other people of color at a higher rate than white people. Still, it’s one of the major tools of modern surveillance, particularly when it comes to protests. During the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests, The NYPD used facial recognition to identify, locate, and attempt to arrest an activist without a warrant. The police cited the activist’s Instagram account in their reports, which is becoming the norm.

Nicol Turner Lee: As this technology becomes much more embedded outside of protected law enforcement environments where it’s being used for investigation. We are now seeing facial recognition to analyze faces on social media, whether that’s the individual or the bystander in the photo.

Morgan Sung: All of this has pushed students protesting for Gaza last year to be more diligent about covering their faces. But now, some universities are facing pressure to deploy facial recognition tools on campus and have banned face masks to discourage protests, especially pro-Palestine activity. Private businesses are also facing pressure to cooperate with facial recognition programs. And it’s especially difficult to opt out of being identified because of the sheer number of cameras in public spaces. They’re everywhere. They’re at traffic lights, public CCTV, and guarding private businesses and homes. Footage from dash cams and police body cams can also feed into these databases. If you’ve ever gotten a driver’s license or gone through airport security, your face is definitely in a database.

Nicol Turner Lee: You know, I always say to people, “well, do I mind that there are cameras on the subway system? Probably not, because I’m probably not going to do something quite egregious on the subway system. But when somebody knocks on my door, am I going to feel different?” And unfortunately, disproportionately, people of color tend to be the ones whose doors are knocked on, because there’s a higher likelihood of some type of institutional interaction where they are in somebody’s database.

Morgan Sung: And once again, private tech companies are the key to facial recognition surveillance. The Black Lives Matter activist we mentioned earlier? The NYPD used one of these third party companies to identify him using his Instagram.

Nicol Turner Lee: What third-party companies have done is that they’ve actually engaged in what I call “massive wholesale scraping,” meaning they’re able to identify us in a variety of contexts, both personal and professional. And those images are sort of sold back to the federal government so that they can maintain those databases and those images. I mean, there’s a lot of central intelligence that is basically creeping up across the entire country.

Morgan Sung: In a handful of states, residents have some recourse if they don’t want their face to appear in facial recognition databases. But those protections are inconsistent and the process of requesting deletion is convoluted. You have to make these requests to each company individually and you may have to repeat the process because there’s no opting out of being included again.

Nicol Turner Lee: In the absence of privacy legislation at the federal and state level, guess what? My mother used to say this all the time. “If you’re not in the kitchen, you’re on the menu.” So we are all on the menu, even though we think we live in a society where there’s some level of privacy, maybe in the context of our living rooms. In actuality, when you leave your home and you walk out that door, you are actually in a surveillance capitalist society.

Morgan Sung: So private tech companies are helping the government get around privacy laws and making a profit off of it. But even if we passed stronger laws and closed that legal loophole, it still might not be enough because the reality is, we’ve been surveilling each other for a long time.

Okay, let’s open one last tab, doxing as surveillance.

This practice of tattling on each other has been gaining steam online for years. Think of the seemingly innocuous ways that people are shamed on social media for what others perceive as bad behavior. Maybe they ghosted a new relationship and their bitter ex posted their hinge profile to warn others. Or someone Karen-ed out too hard at a restaurant and their outburst at a server was recorded and went viral. People have been doxxed for less. And now, These public shaming practices are weaponized as a surveillance tactic.

Nicol Turner Lee: I don’t think that people submit to participate on these platforms with the expectation that their information will be used to target them and to weaponize them.

Morgan Sung: What makes this part of the surveillance machine different is that it’s civilians leading it, doing the work of monitoring political speech for the government, like in the case of Rumeysa Ozturk.

Al Jazeera: 30-Year-old rumeysa Ozturk was on her way to break her Ramadan fast with friends on Tuesday when six plain-clothed officers approached her. The neighbor who captured the arrest on surveillance video described it as a kidnapping.

Morgan Sung: Rumeysa is a Turkish student pursuing a PhD at Tufts University. Last year, she co-authored an op-ed in the school paper, which criticized the school’s response to student protests and described the war in Gaza as a genocide. Then, in March, she was doxed. A pro-Israel organization called Canary Mission added Rumeysa to their blacklist. They posted her name, face, and work history on their site and accused her of anti-Isreal activism, citing last year’s op-ed. Weeks later, her visa was revoked and she was arrested.

Canary Mission claims credit for her arrest and those of other visa holders who face deportation for supporting Palestinians. The organization maintains a database of publicly available dossiers on people who they consider anti-Israel or anti-Zionist, including Jewish academics. People have been harassed, threatened, and fired after being doxed on the site. And since the president signed the executive order targeting international students for protesting, Canary Mission has singled out visa holders and other legal U.S. Residents in a new section of their site, calling for deportations. This kind of civilian-led surveillance is especially alarming to legal experts like Dr. Lee.

Nicol Turner Lee: I was a student against apartheid when I was in college, and I was a student urging our university to divest. That is just as similar to what we’re seeing in many of the pro-Palestinian movements with regards to, you know, just some of the things that we’re witnessing on the university campus, where students have, I guess, an implicit understanding that they are protected because they’re in a space of intellectual freedom. To have that happen is just very sad and disturbing. But then the second thing is like, not only the government’s doing it, but we as citizens are helping the governments do that to our fellow citizens.

Morgan Sung: Other civilian-led surveillance groups go even further. Betar U.S., the American branch of a Zionist nationalist youth movement, boasted that they’ve sent deportation lists to the Trump administration. They also claimed credit for the arrest of Mahmoud Khalil, the Syrian-born Columbia student who faces deportation for his involvement in the protests. One of the facial recognition tools Betar uses purports that it can identify protesters even if they’re masked. The tool works by scraping countless photos off of people’s social media accounts. And the developer, Eliyahu Hawila, says he plans to license it to other pro-Israel groups. Here he is, speaking to the Associated Press.

Eliyahu Hawila: I mean if they’re wearing masks they’re trying to hide. But then you ask yourself, “Oh well if you’re proud of yourself and like you don’t think you’re doing anything illegal then why are you hiding your face?”

Morgan Sung: Civil liberties organizations have been fighting to regulate the government’s partnerships with surveillance tech companies. But when civilians use the same technology to dox each other, that’s uncharted territory.

Nicol Turner Lee: The fact that there is a level of implicit consent that that media could also be sent to law enforcement is quite troubling. But it does set up a really terrible precedent if we say that people’s freedom of speech and points of view can be targeted. And we do it in a way that we don’t equally apply that standard to other movements.

Morgan Sung: There’s no expectation of privacy in public spaces anymore. We’ve gotten into the habit of recording everything about our lives and the people around us. Even if you don’t use social media, your face could end up in the background of someone else’s Instagram story.

Nicol Turner Lee: For years we’ve sort of dealt with what’s called “bystander theory” and there’s been a lot of research done on that. You know, tech companies have worked hard over the years to get bystanders to opt in to being in people’s photos. But sometimes you don’t know who that person is. Like I know I’m very mindful myself if I have a photo and I see like these random people in there of like cropping the photo to kind of get them out. But that type of hygiene is not necessarily part of everybody’s toolkit. We take photos and we have a host of people that sit in those photos, and then all of a sudden that person shows up again in somebody’s criminal database or may not have anything to do with what you were doing at this scene, but they’re still sort of pulled into, as my mama would say, your drama.

Morgan Sung: All of this doxing and surveillance could have dire consequences for not only our right to the freedom of speech, but also our willingness to engage in any political issue, both online and in real life.

Nicol Turner Lee: But at the same time, does that mean that we’re going to have folks that are too afraid to post about things other than pilates on many of these platforms? And what does that world look like in the next five to ten years if people feel that it’s just not safe to say what you want to say, not just on social media, but generally? Right? Like if you’re a bystander at a meeting, you’re probably going to be targeted. A speech that you might have made at church, you know, could be picked up by somebody who recorded it, shared it in some way or form, and now they’re coming at you and your three degrees removed from it.

Morgan Sung: The surveillance machine is massive. Between the data collection, facial recognition, and doxing campaigns, protesting can feel more dangerous than ever. But if it’s any comfort, Dr. Lee doesn’t think that people will stop exercising their rights. Activists have weathered surveillance before and figured out ways around it.

Nicol Turner Lee: When I think about the ancestors of people who gave me the right to sit here on this podcast with you and get the education that I have, they believed in something and they didn’t allow that surveillance to break up their social movements, which would be considered the civil rights movement, which led to great policy. So I’m gonna put that out there. I think that that’s not going to minimize how people organize. It’s just gonna influence how their tactics may change. But if you’re a truly engaged activist, the government already has data on you. You know, surveillance is not new to America, and to the world. It is part of capitalism. You know no amount of scrutiny should stop us from wanting to actually elevate good causes and to work in the public interest. It only means that we have to be smarter and we have be more reserved in how we share what those causes are.

Morgan Sung: The right to organize and protest for what you believe in is a fundamental right that should be guaranteed by the Constitution. But we’ve seen how that right is threatened and inconsistently protected. So if you do find yourself at a protest, how should you protect yourself against surveillance?

Jalsa Drinkard: Personally, I will take it off that phone.

Morgan Sung: That’s Jalsa Drinkard:, who we heard from earlier. Getting off your phone, like she recommends, might not be realistic for everyone. But there are ways to protect your digital privacy. You can disable location services for all apps, use encrypted messaging services like Signal to talk to your fellow organizers, and turn off your phone when attending protests. We’ll link some more privacy resources in the episode description. And before you post any pictures or videos online, consider some of that digital hygiene that Dr. Lee talked about. Is anyone else’s face visible in your post? Did strangers in the background consent to being recorded and posted? Staying informed about how to protect yourself from surveillance is a community effort, which is why Jalsa recommends connecting with other organizers.

Jalsa Drinkard: Meet up in person, and then like a good old coffee shop. That’s where a lot of the movements happened, they happened in coffee shops and libraries where there wasn’t any cameras.

Morgan Sung: The activists of the past didn’t have the tech that we have today, but they did face huge hurdles when it came to surveillance, and that didn’t stop them from organizing. Surveillance may be ingrained in American culture, but so is protesting.

Since we produced this episode, there’s been a development. Rumeysa Ozturk, the Tufts student who was detained after writing an op-ed, was released after spending six weeks in a detention center in Louisiana. Okay, let’s finally, close all these tabs.

Close All Tabs is a production of KQED Studios and is reported and hosted by me, Morgan Sung. Our Producer is Maya Cueva. Chris Egusa is our Senior Editor. Jen Chien is KQED’s Director of Podcasts and helps edit the show.

Special thanks to Don Bell, Jalsa Drinkard, and Nicol Turner Lee for sharing their perspectives and expertise in our Surveillance Machine series. And shout out to George Hofstetter for connecting us with Columbia’s student organizers.

Sound design by Maya Cueva and Brendan Willard. Original Music by Chris Egusa. Additional Music by APM. Mixing and mastering by Brendan Willard. Audience engagement support from Maha Sanad and Alana Walker. Katie Sprenger is our Podcast Operations Manager and Holly Kernan is our Chief Content Officer.

Support for this program comes from Birong Hu and supporters of the KQED Studios Fund. Some members of the KQED podcast team are represented by the Screen Actors Guild, American Federation of Television and Radio Artists, San Francisco, Northern California Local.

Keyboard sounds were recorded on my purple and pink Dustsilver K84 wired mechanical keyboard with Gateron red switches.

If you have feedback or a topic you think we should cover, hit us up at CloseAllTabs@KQED.org. Follow us on Instagram @CloseAllTabsPod or drop it on Discord. We’re in the Close All Tabs channel at discord.gg/KQED. And if you’re enjoying the show, give us a rating on Apple Podcasts or whatever platform you use.

Thanks for listening!