Episode Transcript

This is a computer-generated transcript. While our team has reviewed it, there may be errors.

Katrina Schwartz: Hey everyone, I’m Katrina Schwartz and you’re listening to Bay Curious, the podcast that answers listener questions about the Bay Area.

Today’s question comes from listener Scott Brenner in San Francisco. He grew up around here and knows a lot of the local establishments.

Scott Brenner: There are a few restaurants that I know my parents have been to since before I was born. And of course that’s a long time for me, but I know that there’s much more history in this area, so it’s got me wondering: what are the oldest businesses in the Bay Area?

Katrina Schwartz: It turns out there are a lot of businesses that have been doing their thing for a really long time. There’s a car dealership in San José, Normandin’s, that started out selling horses and buggies in 1875. And KCBS is understood to be one of the oldest radio stations in the world, getting its start around 1909.

Scott Brenner: I did have a couple guesses.

Katrina Schwartz: Scott considered Ghirardelli chocolates, It’s-It ice cream sandwiches, but then he settled on one.

Scott Brenner: What I’m imagining is like Levi Strauss, like the apparel company would probably be number one.

Katrina Schwartz: Levi Strauss of blue jean fame is in fact one of the oldest businesses in the Bay Area. So today on the show, we’re going to learn more about those blue jeans and Levi’s. And then we’ll grab a bite at the oldest restaurant in California. Stay with us.

Today we’re visiting two of the Bay Area’s oldest businesses. To start us off, reporter Katherine Monahan takes us to where they both began in downtown San Francisco.

Katherine Monahan: Levi Strauss world headquarters takes up a whole city block at the foot of Telegraph Hill. There’s a landscaped plaza out front, where dozens of employees are getting lunch from food trucks and chatting by giant water fountains. These days, Levi’s is a massive enterprise, operating in over 120 countries.

But it started much more humbly.

Tracey Panek: Levi Strauss and Company was born on the foundations of the Gold Rush.

Katherine Monahan: Tracey Panek is Levi’s historian and director of archives, and she means that literally.

Tracey Panek: When I come to work in the morning, I literally am walking over the remains of a Gold Rush-era ship.

Katherine Monahan: Yeah, we’re standing on top of it right now. In fact, much of San Francisco’s financial district is built on landfill that includes old ships — abandoned when their sailors ran east to look for gold.

Tracey Panek: From 1849 up until the mid-1850s there were thousands of people coming in, and there were hundreds of ships that were coming in.

Katherine Monahan: On one of them was a young Bavarian man called Levi Strauss. He came in 1852 or 53 to open a branch of his family’s dry goods business — which was already operating in New York. He got a warehouse here in San Francisco and started selling supplies — including canvas, bedding materials, and an especially sturdy cotton fabric called denim.

And business went well! Even after the gold rush tapered off, there was still plenty of demand.

Tracey Panek: There’s lots of men who are doing tough outdoor work.

Katherine Monahan: And in the early 1870s Strauss started making a new product, one that would make his fortune. It started with a letter from a customer, a tailor in Reno called Jacob Davis.

Tracey Panek: He also tells Levi about an unusual idea he had for making tough work pants. And it comes down to … here we go ’cause I have some of these — a little tiny piece of metal.

Katherine Monahan: Davis had started putting copper rivets onto the stress points on work pants — just like you still see on your jeans’ pockets today. He told Levi Strauss the pants were selling like hotcakes and he couldn’t keep up. He wanted a business partner.

Tracey Panek: So Levi and the company agree, and on May 20th, 1873, they receive a U.S. patent. For an improvement in fastening pocket openings. We refer to it here at Levi Strauss as the birth of the modern blue jean, or 501 as it would be called.

Katherine Monahan: For a closer look, Tracey takes me up to the top floor — and into the Levi’s archives room.

Katherine Monahan (in scene): And I noticed you put on your white gloves just now.

Tracey Panek: I did put on my white gloves. Most of the collection in the archives is garments and we handle them in a way that’s gonna make them last for another 150 plus years.

Katherine Monahan: It’s a climate controlled room, and hanging from the walls are bits of history. Albert Einstein’s jean jacket from the 1930s. A fluffy suede coat from when Levi’s outfitted the U.S. Olympic team.

Tracey Panek: The important things we keep in a fireproof safe, which I’m happy to show you.

Katherine Monahan (in scene): Yeah, let’s check it out.

Tracey Panek: Alright. So. I’m gonna pull out the very earliest.

Katherine Monahan: Carefully, Tracey carries a bundle over to a table and unwraps the oldest known pair of jeans in the world.

Katherine Monahan (in scene): Whoa.

Tracey Panek: This pair has been through the ringer, and has lost a lot of the blue indigo that makes them the blue jeans that we know of. There’s lots of speckles and dirt.

Katherine Monahan: These are from 1873 or ’74. They’re a mottled greyish brown, and the crotch is completely worn through. Most of the metal is gone. What’s left of the denim has been stitched to an inner layer to stabilize it.

Tracey Panek: We worked with a conservator creating kind of an inner ghost pair of blue jeans, to then sew all of the parts that may have been just hanging.

Katherine Monahan (in scene): I’m just thinking how meticulous … like it’s making me think of archeologists who recreate the face of a Neanderthal woman or something like that.

Tracey Panek: Oh no, it is. It was stitch by stitch. And look at them, it was difficult to put the needle through because the denim was still really tough.

Katherine Monahan: The original Levi’s were serious work pants, basically personal protective gear to be worn on top of your other clothes. They had buttons for suspenders and a buckle on the back, so that the size was adjustable.

Tracey Panek: You could get a large pair. Especially if you were like a mining company and you would just get several sizes, kind of big, and then more than one worker could wear them.

Katherine Monahan: The 501 waist overalls, as they were called, were a hit. By 1879 they were selling for $1.46 a pair! Levi’s opened a factory and made jeans here in San Francisco for well over a century.

And the demand kept growing. One old advertisement quotes the 1926 world champion rodeo rider Lawton Champie:

Voice Reading Lawton Champie Quote: I have worn Levi Strauss overalls ever since I was a small boy. I am over 23 years old. The Levi Strauss are the only clothes that will really stand the hard, rough brush work of a cowboy on the range, and they also are neat to wear.

Katherine Monahan: In World War II the U.S. government declared jeans an essential commodity, available only to defense workers. Soldiers wore them while serving overseas, which helped introduce them to Europe and Japan. In the ’50s Marlon Brando wore them with his leather jacket and his motorcycle when he played Johnny in The Wild One.

Movie Clip: Johnny what are you rebelling against? Whaddaya got?

Katherine Monahan: Jeans became the official uniform of cool. By the 1970s, everybody was wearing them.

Jefferson Airplane commercial: Right now, with your white Levi’s, white Levi’s come in black …

Katherine Monahan: The company is still going strong, and still based in San Francisco, though these days the jeans are made mostly overseas.

Katherine Monahan (in scene): What has made Levi’s carry on for so long?

Tracey Panek: So I showed you the very oldest pair of blue jeans that we have in the collection dating to the 1870s. They don’t look a lot different to the Levi’s that we wear today.

Katherine Monahan (in scene): So you think it’s really kind of about the jeans themselves?

Tracey Panek: I think it’s about the jeans themselves.

Katherine Monahan: Levi Strauss capitalized on one of the main needs for people coming to San Francisco in its early years — clothing and supplies. Now let’s go a few blocks down the street to a business that addressed an even more fundamental need –- food. And this business is even older.

Jose Maximilian Paredes: As a matter of fact, it’s older than California state itself.

Katherine Monahan: Jose Maximilian Paredes is a bartender at Tadich Grill in San Francisco’s financial district.

Jose Maximilian Paredes: ‘Cause, uh, California became union in 1850. So Tadich Grill, it was a year before.

Katherine Monahan (in scene): So what you’re saying is this restaurant is older than the state of California.

Jose Maximilian Paredes: It is.

Katherine Monahan: He’s worked here for 25 years and he’s showing me around the place before it opens for the day. It’s classy but comfortable. It feels a little like someplace out of The Godfather, with dark wood paneled walls and white linen table cloths. Along one wall are private booths with wooden dividers.

Jose Maximilian Paredes: It’s like a little small room and you and your guests, you know, nobody bother you.

Katherine Monahan: Tadich Grill got its start in 1849 in a tent on an almost mile-long wharf jutting out from San Francisco’s main harbor, where three Croatian immigrants served food and coffee to merchants and sailors. Their names were Nikola Budrovich, Frano Kosta, and Antonio Gasparich, and they called their little spot Coffee Stand.

Sounds of the kitchen

Katherine Monahan: Over the next 175 years the restaurant passed through just a handful of Croatian owners, including one John Tadich who renamed it after himself in 1912. Since 1928 it’s been in the Buich family. It has never closed, and while it’s moved around a little bit, it’s still in the same neighborhood. And once again getting ready to open for lunch.

Jose Maximilian Paredes: This is our kitchen. This is our chef Jeff Rodriguez. How you doing? Our kitchen, based on three cooks, is serving 400 customers a day.

Katherine Monahan: Before COVID, he says it was more like 700.

Jose Maximilian Paredes: That’s for three people. That’s impressive. So you have the broiler on the side here. This is a charcoal wood mesquite.

Katherine Monahan: Tadich Grill cooks fish over wood coals — in the Croatian style. seafood has always been a specialty here. It was a working class food in San Francisco’s early days. Cracked crab was on the menu in 1916 for 35 cents.

Jose Maximilian Paredes: Really good food. I’ll tell you.

Katherine Monahan (in scene): What’s your favorite?

Jose Maximilian Paredes: Cioppino. Have you ever had cioppino before?

Katherine Monahan (in scene): No.

Jose Maximilian Paredes: Cioppino is like a seafood stew, like a … it is like clams, mussels, prawns…

Katherine Monahan: Jose says he would eat it every day if he could. And he’s clearly not the only one who appreciates the food. Over the years, many famous people have dined here.

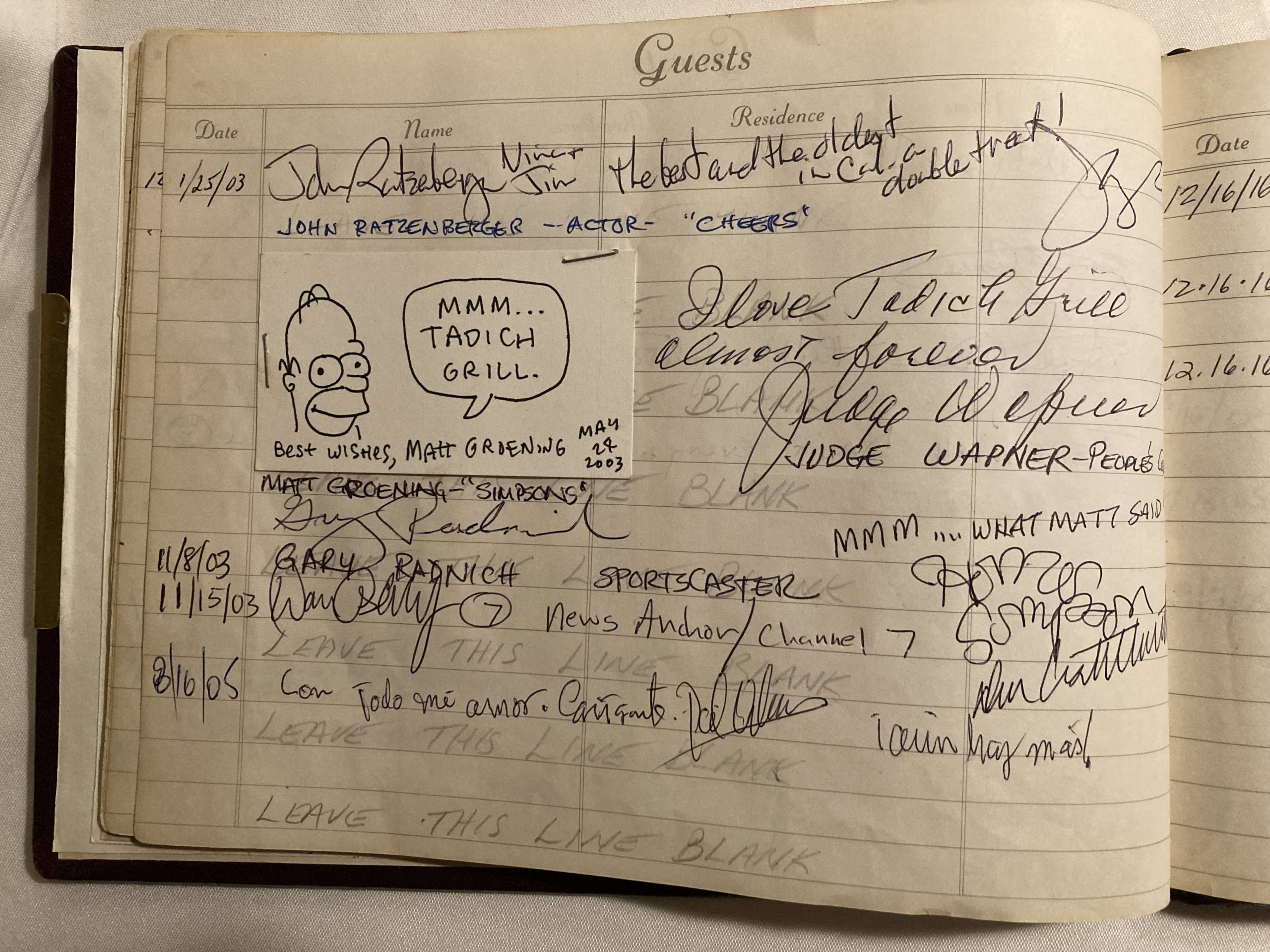

Jose Maximilian Paredes: This is our guestbook. It’s not everybody will have the pleasure to see it.

Katherine Monahan: He sets a well-worn book with yellowed pages onto the table.

Jose Maximilian Paredes: Go ahead. Just go little by little.

Katherine Monahan: There’s page after page of loopy signatures … sometimes with little comments about the food or the hospitality.

Katherine Monahan (in scene): Jack Nicholson. Johnny Carson. Linda Ronstadt.

Jose Maximilian Paredes: Yeah. They all were here.

Katherine Monahan (in scene): Carrie Grant. Doris Day …

Katherine Monahan: Matt Groening, the creator of the Simpsons, drew a cartoon of Homer Simpson saying “Mmmm … Tadich Grill.”

It turns out a lot of San Francisco’s mayors have been regulars. Willie Brown said when he really wanted to show people the flavor of San Francisco, he would bring them here. Several Kennedys have dined here, and George and Barbara Bush.

Katherine Monahan (in scene): Huey Lewis …

Jose Maximilian Paredes: Oh, I remember I waited on Huey Lewis. I have pictures with him. He was sitting right there in that corner right there.

Katherine Monahan (in scene): David Bowie.

Katherine Monahan (in scene): What fun. What a fun place to work.

Jose Maximilian Paredes: It is.

Katherine Monahan (in scene): I remember when I started working here and I said, you know what, I’m just gonna stick around for a few years. I’m gonna make a few dollars and I’m gonna move on. But then for some reason I started liking it, loving it with passion, you know. When you engage with customers and then you laugh and you smile, and then you talk to ’em like you know them for a hundred years.

Katherine Monahan: And now the grandfather clock shows it’s almost 11 a.m. — opening time. Customers are starting to line up outside. Jose turns on the light for the neon Tadich Grill sign out front.

Jose Maximilian Paredes: Here we go. Alright. Yeah. Ready? We’ll find out.

Katherine Monahan: As he opens the doors, families and groups of colleagues step inside.

Jose Maximilian Paredes: Morning. Welcome. Hi there. How are you?

Katherine Monahan: One guy comes in, sits at the bar, and starts folding silverware into napkins. He doesn’t work here though; he just feels really comfortable.

Katherine Monahan (in scene): What you doing?

Matt Ricci: I’m helping out, like I usually do.

Katherine Monahan: His name is Matt Ricci. He likes to get some lunch or a drink and shoot the breeze with the staff. But when he first came in here, almost 30 years ago, it was to work.

Matt Ricci: When I moved here from New York, the guy that I worked for did maintenance at night. And I used to come here and actually clean the kitchen.

Katherine Monahan: That didn’t really pay enough for him to be able to dine here. But then …

Matt Ricci: I started working in finance and then when I could afford to eat lunch every once in a while, that’s, uh, that’s what I did.

Katherine Monahan (in scene): So first you were cleaning the kitchen at night and then next thing you knew, you were like in a suit and tie having a nice white wine.

Matt Ricci: Yep. Yep. Martini’s my choice though.

Katherine Monahan (in scene): How’s the martini here?

Matt Ricci: Ah, it’s the best.

Katherine Monahan: Now he’s here two or three times a week.

Matt says overall it’s the consistency of this place that he loves. That in all these years, it hasn’t really changed.

Matt Ricci: It’s like a treat for a lot of people to come here. It’s that old school goodness that, you know, that people love.

Katherine Monahan: I asked our question asker, Scott Brenner to stop by for a bite and shared all that I found with him. Like how this place has been in business since before California was a state.

Scott Brenner: That’s really quite impressive. I had no idea.

Katherine Monahan: We order the cioppino as Jose recommended — a San Francisco dish that’s almost as old as the restaurant itself. The waiter brings us bibs so we don’t get it all over our clothes.

Scott Brenner: I have to say I’m normally not the biggest seafood person, but at a place like this, it works for sure.

Katherine Monahan: It’s warm and garlicky and fun to imagine diners enjoying this same dish some 150 years ago. Maybe even while wearing a pair of Levi’s.

Katrina Schwartz: That was reporter Katherine Monahan.

Thanks to Scott Brenner for asking today’s question, which actually won a Bay Curious voting round. We’ve got three new questions for you to vote on in May:

Voice 1: There is a placard in Alviso describing how in 1890, P.H. Wheeler wanted to turn the salt marsh into a development called “New Chicago” but that fortune’s tide turned against him. Who was P.H. Wheeler and what happened?

Voice 2: What is the longest stairway in San Francisco? What is the shortest? What is the steepest?

Voice 3: Who funds those positive billboards in Oakland along 880? They went up right after the election and they l say things like “yesterday’s tomorrow is here today” or “what if that thing were a good thing.” They’re positive.

Katrina Schwartz: Head on over to kqed.org/baycurious to cast your vote. And if you’ve been wondering about some aspect of life in the Bay Area, you can submit your question there too.

Bay Curious is made in San Francisco at member-supported KQED.

Our show is produced by: Gabriela Glueck, Christopher Beale, and me, Katrina Schwartz.

With extra support from Alana Walker, Maha Sanad, Katie Springer, Jen Chien, Holly Kernan, and everyone on team KQED.

Some members of the KQED podcast team are represented by The Screen Actors Guild — American Federation of Television and Radio Artists San Francisco-Northern California Local.

See ya next week!