Episode Transcript

This is a computer-generated transcript. While our team has reviewed it, there may be errors.

Olivia Allen-Price: The naming of things is a serious matter, something we’ve all been paying a bit more attention to in recent years. Who do we memorialize and why? If the honorees don’t merit a mention in school books, who even remembers them after the last living person to know them dies? I’ve been thinking about this a lot ever since we got this question from longtime listener Pete Smoot.

Pete Smoot: Who is Stevens, and why is Stevens Creek Boulevard in San José and in Cupertino named after him or her?

Olivia Allen-Price: Pete’s driven along Stevens Creek Boulevard. He’s hiked in the Stevens Creek watershed, which tumbles down from the Santa Cruz Mountains to the San Francisco Bay. He used to ride his bike around the Stevens Creek Reservoir. And he couldn’t help but notice a lot of things in the South Bay named after somebody named Stevens.

Pete Smoot: The whole reason to name something after someone is to memorialize them. And we’re failing.

Olivia Allen-Price: This week, we’re digging into the all-but-forgotten history of Elisha Stephens. It’s a tale full of adventure that will take us over the high Sierra a few years before gold was found in this state. I’m Olivia Allen-Price. This is Bay Curious. Stay with us.

Sponsor message

Olivia Allen-Price: OK, so Pete wants to know why so many things in Cupertino, Mountain View and Sunnyvale are called “Stevens Creek.” KQED’s Rachael Myrow did some digging, and here’s what she found …

Rachael Myrow: You know how most searches start on the Internet? Well, the first thing I realized upon looking for Elisha Stephens was there are a lot of different spellings of his name. And the right one is not the one that’s on all the place names and street signs. Author Dan White — whose book “The Cactus Eaters” includes a passage on Stephens — explains.

Dan White: Elisha Stephens, spelled E-L-I-S-H-A, last name Stephens, S-T-E-P-H-E-N-S. He’s commemorated, but misspelled egregiously, in so many landmarks around Silicon Valley, which is kind of bizarre.

Rachael Myrow: I met Dan, along with Pete, our question asker, at Stevens Creek County Park in Cupertino to discuss the story of a South Carolina born man who was, by his own account, under-appreciated during his lifetime — and also, by a lot of other accounts, deserved to be remembered better than he has been.

Music

Dan White: Essentially, he was a part of an immigrant party that opened up what is now known as Donner Pass.

Rachael Myrow: That Donner Pass? The one 9 miles west of Truckee, where desperate pioneers ate each other? Yes. Fun fact: The Donner Party was not the first wagon train to cross this particular mountain pass. The Stephens-Townsend-Murphy Party was! They began in what was then the Iowa Territory. Stephens joined when they stopped in St. Joseph, Missouri. Reflecting their collective respect for his leadership skills, the 50 people in eleven wagons elected him captain.

Dan White: The rub is that this entire overland party did not lose a single man, woman or child at all. In fact, it increased by two because of procreation. They came down from the mountain with more people than they started out with, and and yet, who is the pass named after? The Donners, who made a colossal mess of it.

Rachael Myrow: Which is not to say that the Stephens Party had an easy time of it when they crossed the pass in 1844. Enough beaver trappers and such had made the journey to California that people back East knew going in the hardest part of the journey would be at the end of it.

Music

Rachael Myrow: A Northern Paiute tribal leader who helped thousands of white people in the 1840s and ’50s cross the barren Great Basin of Nevada suggested the party follow a river up to its source in the Sierra Nevada mountains. The guide would often shout, “Tro-kay!” meaning “Everything is alright!” and that’s how a number of things, including the river, were later named “Truckee.” In any case, it was a miserable, hard slog, especially for the pregnant women and the oxen.

Dan White: At one point, there was a granite ledge that they got towards, and there was a 10-foot rocky barrier blocking the way. And instead of giving up, what they did was they unpacked everything from the wagons, and they hoisted each one up that ledge, and they used a rope pulley chained to the backs of the oxen.

Music

Rachael Myrow: Once Stephens and the rest of the party made it down to the promised land of California, easy living lay ahead. As a young man, Stephens was a blacksmith and trapper. Now in his 40s, he settled in what we call Cupertino, buying 160 acres of land originally part of the Spanish/Mexican land grant known as Rancho San Antonio. Stephens named his patch of paradise Blackberry Farm. And a decade later, he essentially doubled his land holdings with more acres in Mountain View.

Through legal means at the time, but the broader context of land ownership in California during the mid-19th century is … complicated, given that Americans took California from Mexico, which took it from indigenous peoples.

But back to opening that mountain path to the Pacific …

Dan White: It became a huge, big deal. It was part of the incursion into California. The 49ers used it, other immigrants used it, and a railroad and a freeway would both breach that same pass. Millions more people going from that same mountain notch.

Rachael Myrow: Possibly because nobody in the Stephens party died, White surmises major newspapers of the day didn’t cover its arrival. That might explain why Stephens felt he had to toot his own horn to South Bay neighbors. They knew about his most famous exploit. But at the time, he was most famous or infamous, for his favorite dish.

Dan White: He was well-known for making an exceptional ragout that was made out of the fat and juicy rattlesnakes that he caught in the brush around Cupertino. And some people avoided his house because they knew that if we went to see him, rattlesnake was on the menu.

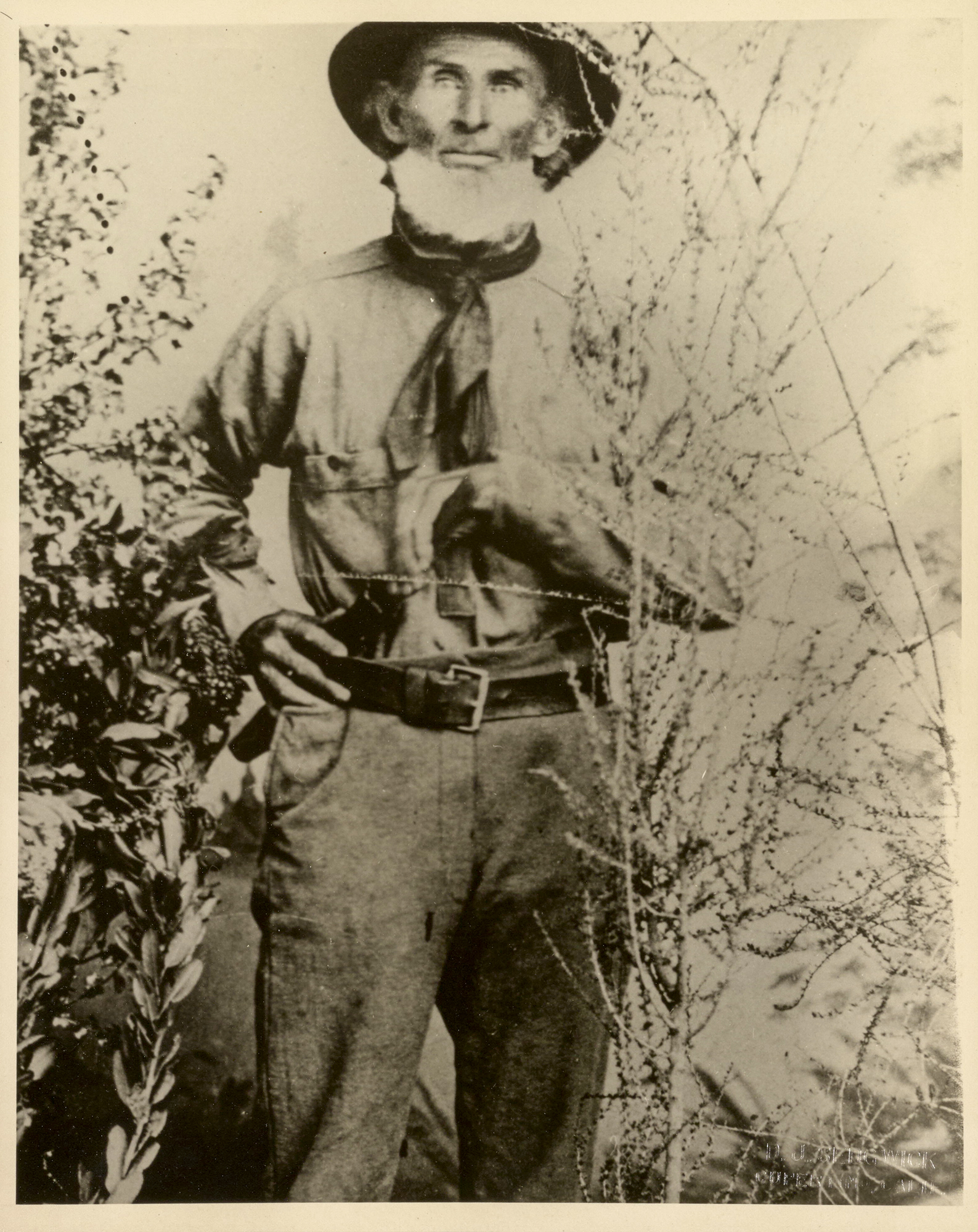

Rachael Myrow: Elisha Stephens became a beekeeper and a chicken farmer. There’s only one known photo of him, and he looks like what you’d expect a 19th-century pioneer to look like: from his hat to his utility knife hanging from his big, big belt. He was tall and skinny, with deep, sunken eyes and cheekbones, a scraggly, snow white beard that extended down to his rough and ready Western cravat, and a piercing, direct stare that was common in studio photos of the time, because if you smiled the whole thing was likely to come out blurry.

Dan White: He became a real grump.

Rachael Myrow: Never married. Never had any kids that we know about. In 1862, he moved to Bakersfield, complaining that the South Bay had become “too durn civilized.” And this was before the sun-baked suburbia we’re all familiar with today.

Music

Dan White: Very tellingly, in the late 1860s, after the Central Pacific Railroad uh route across the mountain pass was finished, I think it would have been classy for somebody to invite him to the ribbon cutting ceremony, but they didn’t. Nobody thought to invite him.

Rachael Myrow: Awwww. It gets worse.

Dan White: One day, he ends up with a stroke. He’s paralyzed in the local hospital. This is when he’s living in Kern County. Then he drops dead. He was initially in a potter’s field in Bakersfield.

Rachael Myrow: A potter’s field is a burial ground for poor, unidentified or unclaimed individuals.

Dan White: The cemetery even lost his internment records. But in 2009, somehow, some historical-minded people found his grave. So at least they found his grave. But I mean, that’s a lot of forgetting and a lot of obscurity, even during one’s lifetime, let alone afterwards.

Rachael Myrow: So how did a guy most everyone forgot get so many South Bay place names named after him? We’ll never know for sure, but Stephens wouldn’t be the only faded-glory pioneer with big land holdings to get memorialized in this particular way in California. What is unusual is the misspelling.

Dan White: This is just my pet theory, okay? Now, there is an author named George R. Stewart, who wrote some really popular books about the Donners, about Donner Summit, about all those explorers, and over and over again, he misspelled Stephens’ last name S-T-E-V-E-N-S. I mean, this stings me on a personal level because I can also tell you from first-hand experience, that a one-time bureaucratic error, can be sustained over time in the most egregious ways. For example, my name — my byline — is Dan White, W-H-I-T-E, which is a horrific misspelling.

Rachael Myrow: Because many people, especially locally, would think of the Dan White infamous for killing San Francisco Supervisor Harvey Milk and Mayor George Moscone in 1978.

Dan White: I descend from Ukrainian and Russian and German Jews, and the last name should be spelled as it was spelled for hundreds and hundreds of years, W-E-I-T. It’s a mistake on my father’s birth certificate that was never corrected. So I’ve got that in common with Stephens. Our last names are butchered, and also with consequences, right? I think what people often say is say whatever you want about me, but spell my name right.

Rachael Myrow: That gets a rise out of our question asker, Pete Smoot.

Pete Smoot: My family name was a misspelling from about 400 years ago. It gave us a very unique last name. So now, when I see someone with the same name, I can assume that they’re related to me. But yeah, I’m with Dan. Call me anything you want, but at least get my name right.

Rachael Myrow: Much of the terrain that attracted Stephens to settle here during the 1840s is still parkland, full of oak trees, wild turkeys, bobcats, burrowing owls — and in the springtime, dotted with periwinkle and Indian paintbrush flowers.

Pete Smoot: The valley floor itself is all suburbia and companies. Yeah, but get up into the hills, and the hills are beautiful. They’re filled with trees and wildlife and babbling brooks.

Rachael Myrow: Is this story that you’re hearing, is it what you expected to hear? Are there surprises in it for you?

Pete Smoot: I didn’t really have an expectation. It makes perfect sense, and I’m not surprised to hear it. I mean, this area was filled with people who migrated from the East Coast. I’m one of them. When there was a land rush in the 1840s, people would have grabbed chunks of land. Some people would have risen to prominence, and they get a bunch of stuff named after them.

Rachael Myrow: Not to get too philosophical on you, but it does seem like Elisha Stephens’ story is emblematic of so much of California history writ large. There are these layers and layers of human stories of travail and triumph that just get paved over, as new generations come through and forge their own paths in the Golden State.

Olivia Allen-Price: That was Rachael Myrow, Senior Editor of KQED’s Silicon Valley Desk.

Thanks to Pete Smoot for asking the question this week. It was chosen by you in a public voting round at BayCuriuos.org. There’s a new voting round up now, and we’re asking you to consider questions about tree frogs, metal music in the Bay Area, and “the San Francisco Twins” … a well-known pair of actresses. Head to BayCurious.org and cast your vote for which story you’d like to hear on this podcast next.

Bay Curious is made in San Francisco at member-supported KQED. As you may have heard, funding for public media is at risk right now. You can help KQED continue to offer high-quality, fact-checked news and information by becoming a member today. Learn more at KQED.org/donate. And thanks!

Bay Curious is made by Katrina Schwartz, Christopher Beale and me, Olivia Allen-Price.

Extra support from Katie Sprenger, Jen Chien, Alana Walker, Maha Sanad, Holly Kernan and everyone on Team KQED.

I’m Olivia Allen-Price. Have a great week!