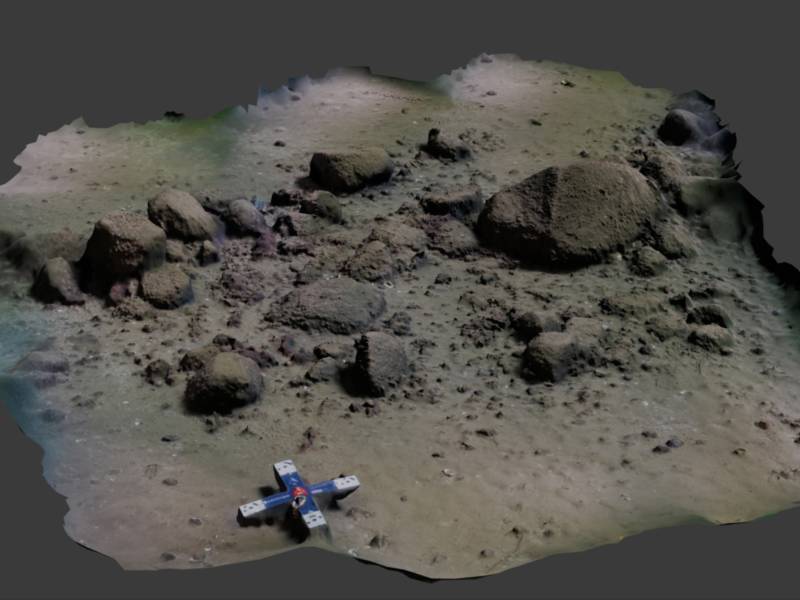

“It’s usually small stones — like tennis or soccer ball size — so movable stones,” Geersen says. “But then, at some places where we have a large stone, the direction of the wall changes.”

Geersen didn’t know how such a structure, which the researchers dubbed the “Blinkerwall” after a nearby underwater mound called Blinker Hill, could have formed naturally.

“It was only when we went to the archaeologists that they said, ‘You may have found something very significant,'” he says.

“I was probably the most skeptical of the entire team,” recalls Berit Eriksen, a prehistoric archaeologist at the University of Kiel who studies the people who arrived in northern Europe when the glaciers retreated after the last Ice Age 10,000 to 20,000 years ago. When she examined the structure from the Bay of Mecklenburg, a line from Sherlock Holmes came to mind: “When you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth.”

“Archaeologists never speak of ‘truth,'” Eriksen says, “but I’m running out of things to eliminate in terms of natural stuff. That’s my problem.”

Eriksen reviewed the data and became increasingly convinced that the structure was made by prehistoric humans who’d used lots of smaller stones to connect the larger, unmovable rocks into a wall. “I don’t believe in UFOs, so it’s got to be manmade,” she concludes. She and the other archaeologists on the project agreed that the wall was likely used by hunter-gatherers 10,000 to 11,000 years ago during the Stone Age to help them herd and hunt reindeer by the hundreds.

How to hunt hundreds of reindeer in the Stone Age

“The only way you can kill this amount of reindeer is if you drive them into a shooting blind if you cut them off at the pass somewhere,” Eriksen says. And reindeer are known to follow these kinds of stone walls naturally, even stout ones like the Blinkerwall.

“There would have been water at the other side,” Eriksen says. So, the reindeer would have become trapped between the wall and the water, allowing the hunters lying in wait to fire their arrows at the reindeer. Eriksen says these prehistoric people were nomadic, but this wall suggests they may have had a regular migration route, one that would have brought them back to this spot year after year.

“If you build a structure like that,” Eriksen says, “you’re someone who knows the entire area extremely well. You’re not just moving around an unknown landscape. You don’t just hope you can find a reindeer that day. You plan. You know where the reindeer will come next year.” It’s a theory that archaeologists have kicked around for a while, but she says this wall helps confirm it may have been true in prehistoric Europe.

Ultimately, the area was flooded, forming the Baltic Sea we know today and submerging this piece of hunting architecture under the water.