California is formally ending its COVID-19 state of emergency Tuesday after almost three years since the pandemic began.

This emergency declaration gave Gov. Gavin Newsom the power to suspend or change laws in California to combat COVID. These legal powers allowed Newsom to issue almost 600 pandemic-related health orders — the majority of which have now been lifted.

On May 11, the White House will lift its own federal states of emergency for COVID, which will have much bigger ramifications for funding around pandemic measures like vaccines, testing and treatments compared to California's earlier move. Californians will be protected, at least initially, from changes around health insurance brought on by the federal emergencies ending — thanks to laws that have been passed within the state in the last few years that force insurers to keep covering certain COVID costs.

The Newsom administration is framing the Feb. 28 date for lifting the California state of emergency as a logical step that was coming at the right time, while acknowledging the crucial role played by these emergency powers in fighting the pandemic. But not everyone agrees it’s the right time to end these emergency powers in the state.

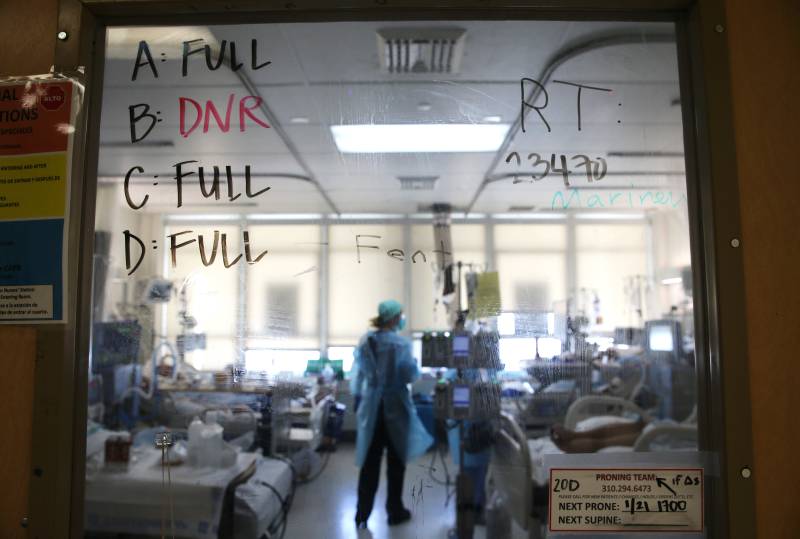

One of those people is Carmela Coyle, head of the California Hospital Association, who told The New York Times earlier this month that February was "a terrible time to end the public health emergency," because of ongoing strain on California’s hospitals.