Driving through the coastal city of Morro Bay, it’s hard to miss the 600-foot-tall volcanic rock sticking out of the ocean and towering over the city. The local landmark is commonly known as Morro Rock, a Spanish word with several meanings including “snout” or “round hill.” But Indigenous people of the area call it by other names: Lisamu’ by the Chumash and Lesa’mo’ by the Salinan.

Chumash Tribes 'Reunite' Sacred Rock in Morro Bay Ceremony

The rock is sacred to both tribes, a central figure in their mythology, although the two groups have ongoing tension over whether the rock should be climbed. The Chumash object to the Salinan tradition of scaling the rock twice a year, on the winter and summer solstices. But what both tribes have in common is a painful history of the sacred rock’s desecration.

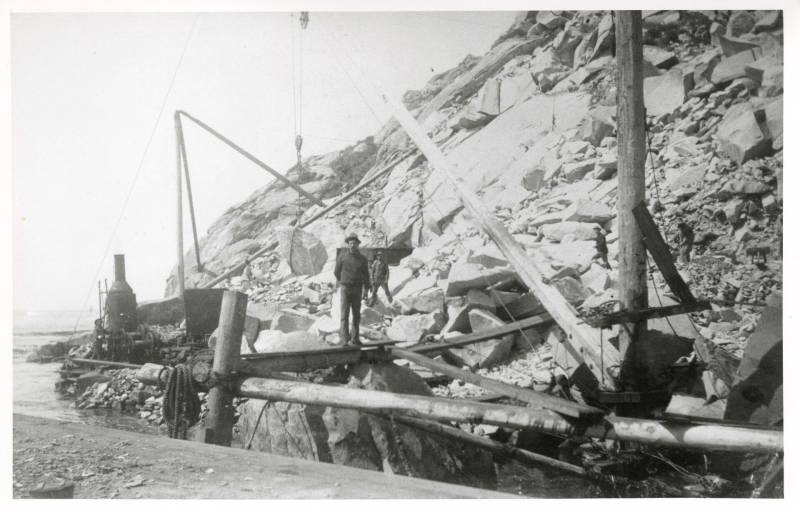

In 1889, the Army Corps of Engineers started heavily quarrying Morro Rock, blasting 250,000 tons of rock over the course of 80 years. They used it to create breakwaters in Morro Bay and nearby Avila Beach, a deeply painful history to the Chumash and Salinan. Blasted pieces of the rock were also used in buildings around San Luis Obispo County and for the road to the rock itself, which used to be an island.

The rock is now about two-thirds of its original size, and shaped differently from how even some living tribal elders remember it.

Road to reunion

In 2017, the Army Corps of Engineers started looking at repairing the nearby Port San Luis breakwater. They reached out to the Northern Chumash Tribal Council (NCTC) to get input on what should happen to the granite that originally came from Morro Rock. Fred Collins chaired the council at the time, and told them he wanted it back.

“He wanted them to put it back together,” said Violet Sage Walker, the current chairwoman of the NCTC, and Collins’ daughter. “I imagine him thinking that they’re gonna, like, glue the rock back together.”

The Army Corps eventually put the project on hold after deciding it wasn’t feasible. But then in 2021, they contacted the Chumash — and the Salinan, who did not get involved and didn’t want to comment on it for this story — and told them they’d found a way to extract some of Morro Rock’s stones from the breakwater and return them to the tribe.

Reuniting the rock

In August of 2022, the NCTC brought the various Chumash tribes together to return recovered pieces of Lisamu’ to their source in a ceremony called Reunite the Rock.

Tribal members rowed traditional wooden canoes called tomols to the sandy shore below the rock. The rowers were greeted on the shore by more tribal members who cheered and sang songs. About a hundred people from all parts of the Morro Bay community looked on excitedly.

Coastal Band of the Chumash Nation member Michael Kiserotti invited everyone — not just tribal members — to form a human chain to pass the stones from the beached tomols to the base of Lisamu’.

“Nothing good happens without community, and nothing really good happens without teamwork and without inclusiveness,” he said at the time.

A seat at the table

Violet Sage Walker described that day as “spectacular.”

“My dad always would tell people, we can do better. And that’s an example of us doing better, doing things with more care and consideration and empathy for other people. It was a pretty amazing event,” she said.

She said it was meaningful to have the Army Corps “stand with us and give us back our rocks, and apologize for things that happened in the past.”

While she appreciated the symbolism of returning the rocks, she said it doesn’t wash away the painful and violent history of this area.

“The rock was blown up right about the time our people and our culture were, too,” she said. “In the 1880s, our people were being killed, [with] state-sanctioned killing of Indigenous people. It was after the mission system, so they were already displaced from their land, and then our sacred places were being blown up.”

It’s a legacy of violence, and one that is still very much in the minds of Indigenous people here. But Sage Walker said her tribe now has a “seat at the table” when decisions are made, a hopeful sign.

For example, a massive offshore wind farm is planned for Morro Bay, as is the proposed Chumash Heritage National Marine Sanctuary in the waters south of Morro Bay. While the tribe doesn’t control those projects, they are being consulted on them.

“It’s bittersweet,” Sage Walker said. “These people, my ancestors, people that have suffered so much aren’t here to see things like this happen. But it hopefully will be easier on the next generation, that they won’t have to go through some of the things that we’ve gone through.”

The Army Corps’ breakwater project will likely pick back up in the spring. The rocks’ return was a symbolic gesture, but for Sage Walker, it’s an indication the Chumash are finally being heard, listened to and included — a small step toward healing.