In the nearly 30 years since Thomas Xiao arrived in San Francisco, he said he’s seen co-workers get injured at restaurants, factories and other jobs. Xiao himself suffered tendons that tore apart in his right shoulder in 2019, a stress injury he believes came from tossing a heavy frier with potatoes over and over for years.

“It became really painful. I couldn’t even lift my hand,” Xiao said in Cantonese through an interpreter with the Chinese Progressive Association, a nonprofit in San Francisco.

But until recently, the 66-year-old Chinese immigrant never considered filing a complaint with California regulators tasked with protecting health and safety in the workplace. Xiao, who now works as a janitor, said he didn’t know Cal/OSHA existed, let alone that the agency can investigate workplace hazards like repetitive-motion injuries.

In one of the country’s most linguistically diverse states, Cal/OSHA officials maintain that a high priority (PDF) is “direct communication” with workers who have limited English proficiency. Because of a lack of English skills or legal status, many immigrants work some of the most dangerous low-wage jobs.

Cal/OSHA’s critical services remain largely inaccessible to those very laborers, leaving them less protected, according to labor experts and worker advocates. A substantial issue is the agency’s woefully insufficient number of bilingual safety inspectors who are required to interview employees while investigating complaints, injuries or deaths at worksites.

That’s even though state and federal laws (PDF) require public agencies like Cal/OSHA, officially known as the Division of Occupational Safety and Health, to take reasonable steps to provide full and equal access to their services to people who don’t speak English well.

Cal/OSHA’s language access gaps are especially pronounced for workers in the state’s large Asian communities, particularly in the Bay Area and Los Angeles and Orange counties.

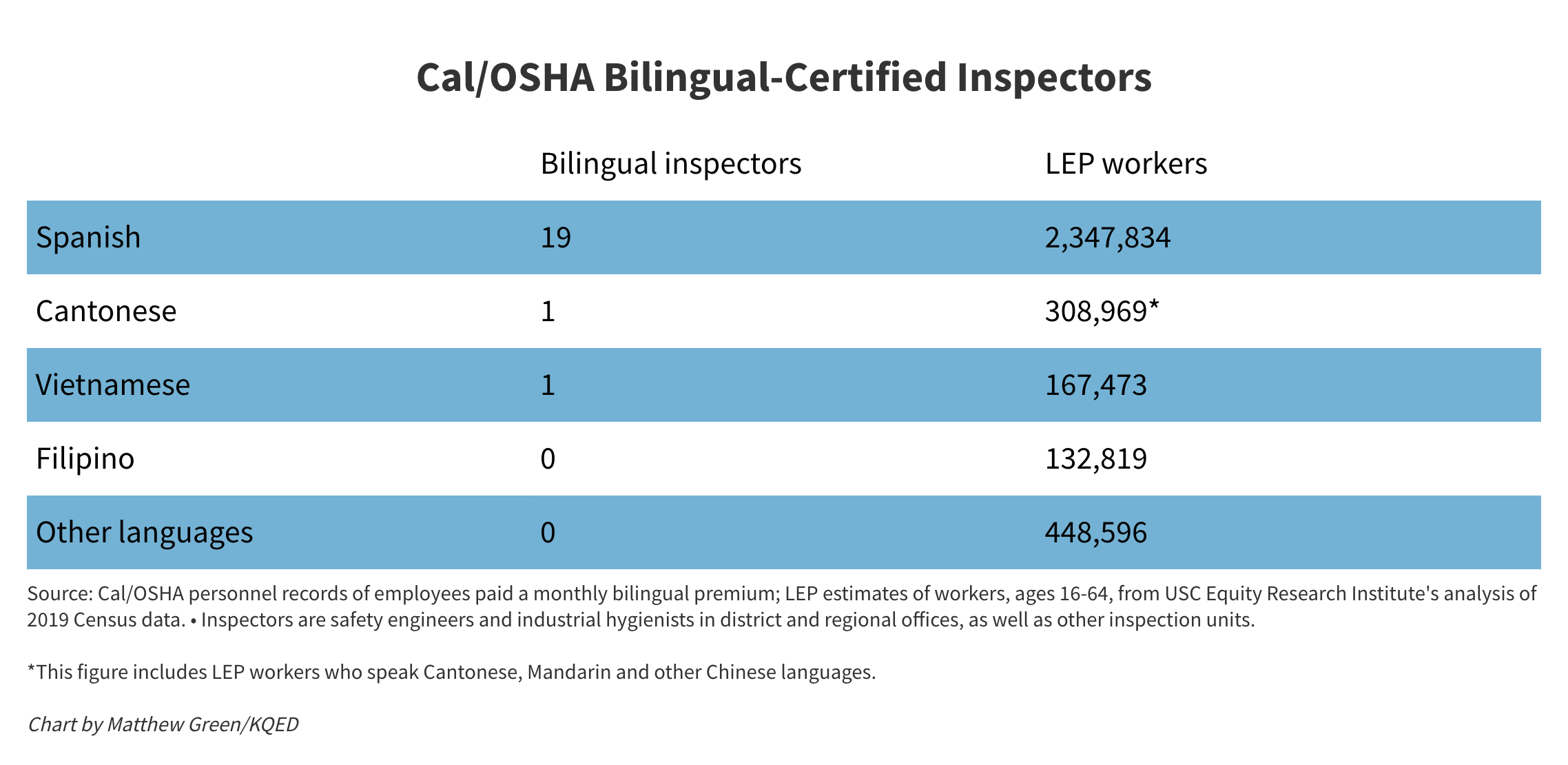

An analysis of 2019 census data by the USC Equity Research Institute conducted for KQED shows the state’s most prevalent languages after English and Spanish are Chinese, Filipino and Vietnamese, which are spoken by roughly 600,000 combined workers with limited English proficiency or none at all.

Of the 214 inspectors employed by Cal/OSHA, just 21 were certified in a second language as of October, personnel records show. Nineteen were Spanish speakers, while only one was fluent in Cantonese and one in Vietnamese.

“This is very surprising, disturbing and disappointing information,” said David Chiu, city attorney of San Francisco, where more workers speak Chinese at home than Spanish, unlike elsewhere in the state.

“When you have literally millions of Californians who speak other languages, who are particularly vulnerable to workplace exploitation, the lack of language ability on the part of Cal/OSHA staff means we don’t know what’s happening at these jobs, we can’t enforce the law, and workers’ lives and health and safety are at risk,” Chiu said.

Cal/OSHA declined interview requests by KQED.

The agency is committed to communicating with workers and employers in their preferred language, said a spokesperson for the California Department of Industrial Relations, which oversees Cal/OSHA and other labor enforcement divisions. Cal/OSHA has additional personnel who speak a second language but are not certified as bilingual, which involves passing an oral fluency exam, the spokesperson said.

Still, two former Cal/OSHA inspectors, also known as compliance safety and health officers, told KQED that the inadequate number of bilingual-certified inspectors suggests how ill-equipped the agency is to conduct investigations involving workers who primarily speak languages other than English.

“I think that’s pretty obvious that they don’t have the same protections as an English-speaking worker,” said Michael Horowitz, a retired Cal/OSHA inspector and enforcement district manager in Oakland. “It’s a lot more difficult for their problems and hazards to be brought clearly to the attention of a state health and safety inspector.”

Since mid-2019, Cal/OSHA has lost about a third of its bilingual-certified inspectors, all Spanish speakers, according to a KQED analysis of agency rosters of employees paid a monthly bilingual premium after they are certified in another language.

As of last month, just 5% of the agency’s total 964 budgeted positions, including outreach workers, managers and legal secretaries, were filled with personnel receiving bilingual pay.

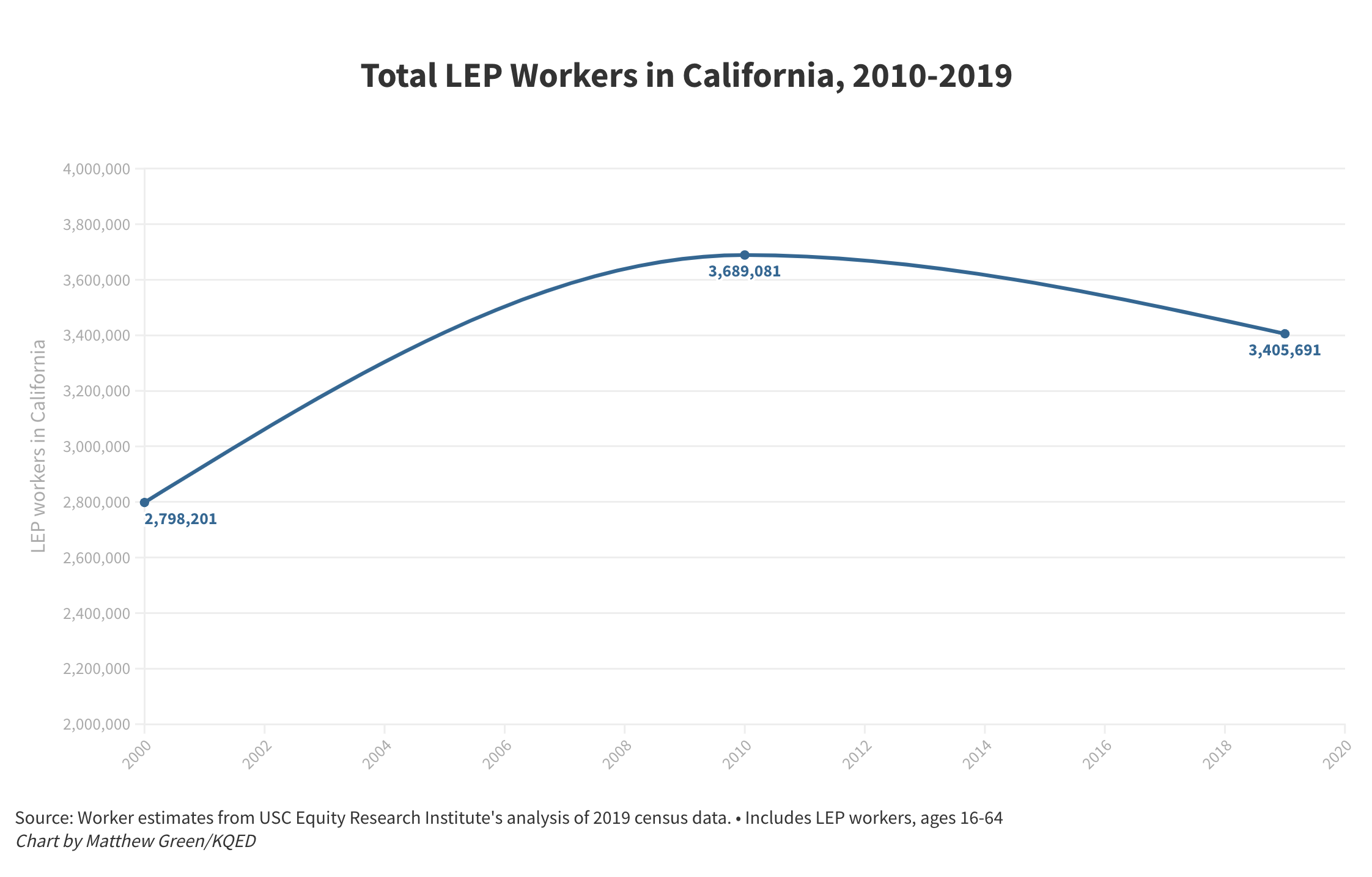

This comes as the number of California workers with limited English proficiency has climbed to 3.4 million — nearly 1 in 5 of the state’s labor force, according to the USC Equity Research Institute analysis.

Using the estimated number of workers who speak other languages at home but report limited English proficiency, KQED calculated a rough ratio of inspectors who can communicate fluently with them.

Chinese-speaking workers experience the largest access gap, with one inspector certified in Cantonese for every 309,000 workers. For Vietnamese-speaking employees, Cal/OSHA has one inspector for every 167,000 workers. And for Spanish speakers, there is one inspector for every 124,000 workers.

Though far from ideal when compared to other states, the ratio of safety and health compliance officers for workers who speak English as a native language or very well is much more protective: one inspector for every 72,000 workers.

‘A lot is lost in translation’

Many immigrant employees in high-risk industries are reluctant to speak up to inspectors about problems they’ve witnessed because they fear losing their jobs or distrust government agencies.

If inspectors are unable to chat directly with workers and gain their trust, they may miss serious health and safety hazards, said Horowitz, who worked for Cal/OSHA for more than 17 years. Effective investigations could eventually lead to fines for employers and safer conditions for employees.

Horowitz said inspectors may rely on a foreman or manager to interpret, but workers will be less likely to speak candidly if their boss is present.

“That is not a good situation to get a true picture of what the workplace hazards might be,” said Horowitz. “A lot is lost in translation. Clearly money could be spent on it, but it’s certainly not a priority that I’ve seen in the state.”