Neda Toloui-Semnani is an Emmy Award-winning writer and producer who’s written for Vice News and The Washington Post. She’s just released her first book, a memoir, “They Said They Wanted Revolution: A Memoir of My Parents.”

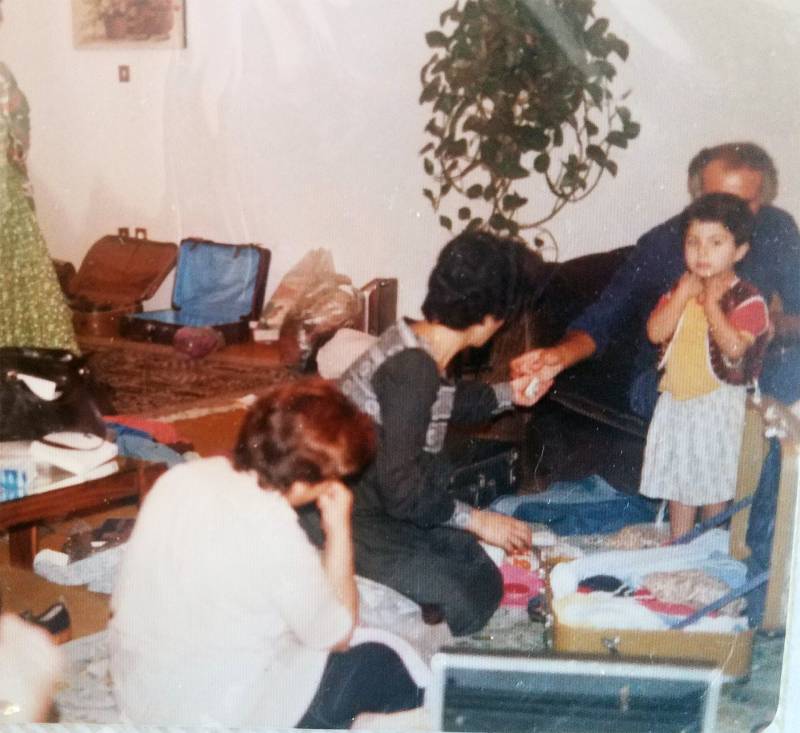

It’s pieced together from interviews, diaries and archives, and dives deep into her family’s history, both in the U.S. and Iran, starting with her grandfather’s decision in the 1920s to choose a surname for his family, and tracing her parents’ return to Iran to support the revolution after they were radicalized as Marxists in the leftist climate of Berkeley in the late 1960s.

Toloui-Semnani spoke with The California Report Magazine’s host, Sasha Khokha. Excerpts of this interview have been edited for length and clarity.

On Iranian students and radical 1960s Berkeley

Whether it’s immigration, or even something as simple as where you go to college, the moment that you touch down someplace can set you on your course. It’s one of the reasons why I spent so much time researching the time and the place, digging into what Berkeley was like in 1969 versus 1965 versus 1972 to get a sense of how Berkeley was changing — how the students within the university, but also the people within the city, were changing.

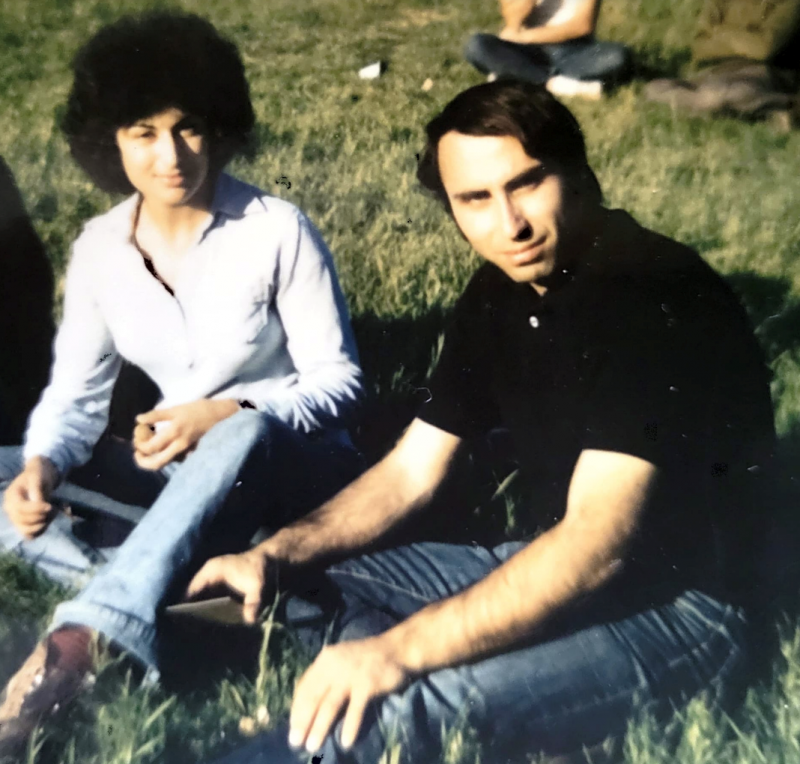

Iranian students [like my parents] were becoming more political and certainly more militant, looking around at groups like the Black Panthers to see how they were doing it. They were very aware of SDS [Students for a Democratic Society]. In fact, some of them were members of both SDS and the Iranian student movement. So these weren’t separate groups. The Iranian students very much influenced those groups and were influenced by them in return. For young people who were feeling that drive to change, there was one part of the spectrum that was drawn to the more militant, radical side of political activism.

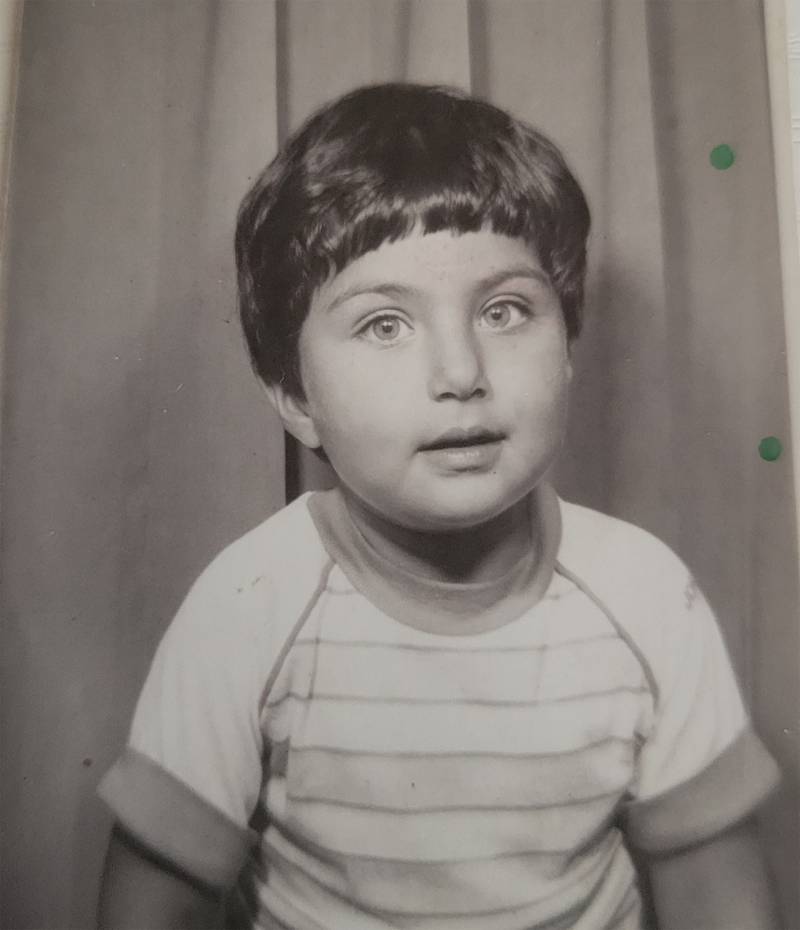

On that first day in Berkeley, she walked hurriedly down Telegraph Avenue. She had a quick, funny gait: heels in and toes out. It pitched her hips back and forth in a way that was a little tomboyish and a little suggestive. She found the sublet, which belonged to a young couple who were visiting Iran for a few months. The apartment was essentially a small room, but my mother took it to share with another Iranian girl I’ll call Naz, who was a few years younger than she, the little sister of a friend.

The girls moved into the studio with a love seat, milk crates, a phone, and a turntable. They slapped fat psychedelic-flower decals on the wall and pulled down the Murphy bed to share. That summer, their apartment was where everyone gathered on their way to the Iran house, the meeting place for all the ISA [Iranian Student Association] chapters in Northern California, a couple of blocks away.

My mother and my father were part of the Iranian student movement, which was an anti-Shah movement. There were various different factions of that. The one thing that really unified them is that they didn’t want the Shah of Iran to be in power anymore. My parents were on the left. They started as Marxist-Leninists, and as Berkeley tracked towards Maoism, which it was wont to do in the early 1970s, so [did] my parents also go further and further to the left.

As the Iranian student movement, the anti-Shah movement, was really becoming established — after the takeover of the Iranian consulate [in San Francisco in 1970], for example — it became illegal to be part of what they call “the confederation,” the Iranian student movement. So then people were starting to cover their faces [at protests]. Looking at old newspaper clippings and video from protests, you’ll see that often they’re wearing masks or hats and sunglasses. And as the ’70s went on, these became full-face coverings. They were very aware that they were being watched [by both the Shah’s secret police and, potentially, the FBI].