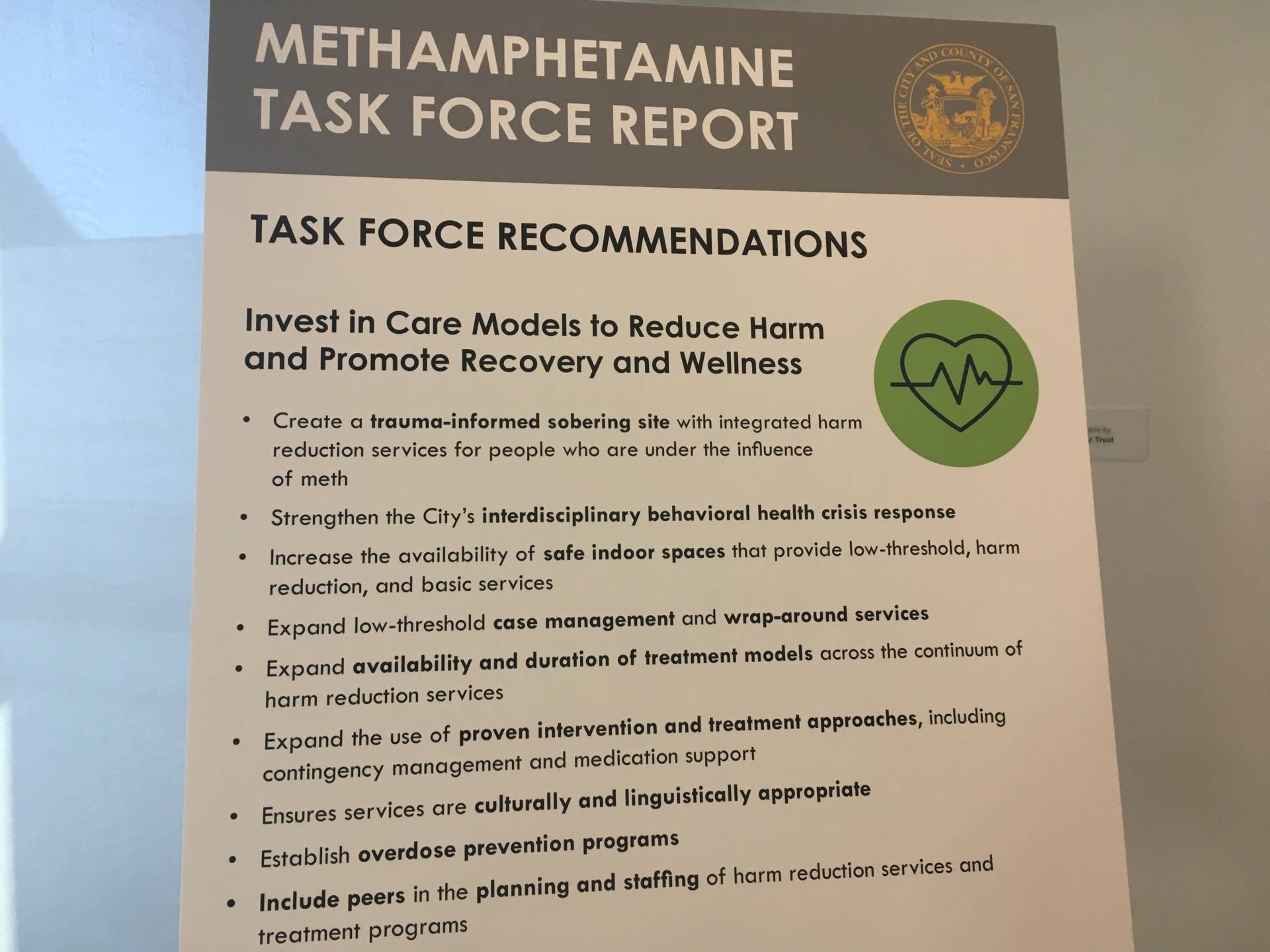

San Francisco Mayor London Breed convened a task force in February to address the fast-growing numbers of meth overdoses and hospitalizations, and on Tuesday the force issued its report, detailing 17 recommendations on how to improve crisis response and treatment options for people with problematic meth use.

New Meth 'Sobering Centers' Top San Francisco's Plans to Address Drug Crisis

The number one recommendation, and one the mayor is acting on immediately, is to open a meth sobering center, a safe place where people who are too high or experiencing meth-induced psychosis can safely come down.

“We need places that are not psychiatric emergency services, that are not emergency rooms, and that are not jail for people who are meth intoxicated,” said Rafael Mandelman, San Francisco District 8 supervisor and co-chair of the task force.

Public health officials say a sobering center will ease the burden on San Francisco General Hospital’s psychiatric emergency services, where almost half the patients admitted every year are high on meth, and instead direct them to a less intensive and less costly place to sober up and learn about long-term treatment options.

“We've operated a sobering center — mainly for people who use alcohol — since 2003, and we will build on what we've learned from that to implement this sobering center and others,” said Grant Colfax, director of the city’s public health department and a co-chair on the task force.

The city is working “furiously” to figure out where these centers can go, Colfax said, with the plan to open the first one in the next three to six months.

The second-highest recommendation was to strengthen the city’s behavioral health crisis response protocol.

“I hear from constituents every day who are seeing folks in distress, folks in psychosis, and they have no idea what to do, who to call, how to get a response,” Mandelman said. “They 3-1-1 it, it doesn’t work. They feel nervous about calling the police.”

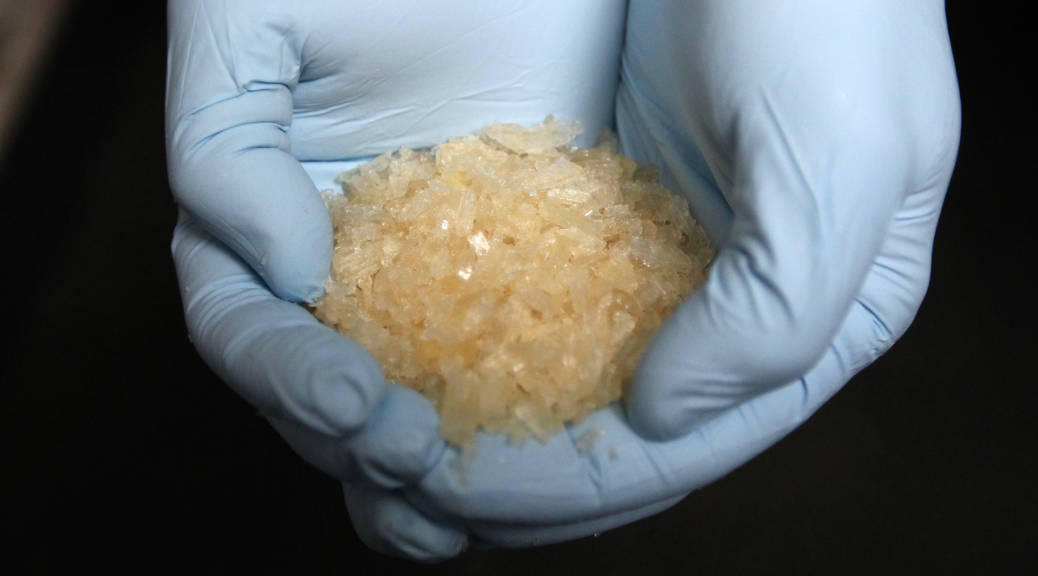

The Methamphetamine Crisis

The Methamphetamine Crisis Instead of 311 or 911, the city plans to set up a separate number and mobile app where people can get a real-time response from street medicine team workers who are trained to recognize and de-escalate people on meth, and who generally have more success convincing people with problematic use to enter treatment.

The task force met four times between April and September and included officials from government, public health, drug treatment services and law enforcement. Focus groups with business owners and residents surfaced complaints of violent encounters, property damage and thefts related to meth use. This year, methamphetamine has been the drug most frequently involved in drug arrests in San Francisco, and among people in the city’s jails, meth is the second-highest reported substance used after alcohol.

“We know that progress is not moving fast enough,” said Breed, who has come under fire from other supervisors who say she is not acting fast enough to address the city’s mental health care needs. “But we need to be responsible in how we coordinate the right system, so it actually delivers the results we need.”

Breed says her plan, Urgent Care SF, will also address the meth crisis. She wants to add 1,000 beds to the city’s mental health system, add more providers and case management services, and expand the city’s conservatorship program to force meth users with repeat hospital admissions into treatment.

“We know that among people with at least eight 5150 psychiatric holds, nearly nine in 10 are users of meth,” she said.

Other recommendations include improving access to treatment, by loosening restrictions on length of stay and number of stays in residential programs, and by creating lower threshold treatment options for people who are not ready for the intensity of a residential program.

Contingency management is one of these lower threshold treatments that got a lot of attention in the task force meetings. It involves giving people vouchers or small financial incentives to reduce or abstain from meth use over a 12-week period. Research shows that it works, but the city will have to cover the full costs, or negotiate with the state over reimbursement policies, because the Medi-Cal program for low-income Californians does not currently pay for this kind of treatment.

Housing was another key focus of the task force. Lack of housing is a driver of problematic use and relapse, it prevents people from seeking treatment at all, and it fuels meth use in public spaces, according to the task force’s final report.

“Something like 44 percent of homeless people who come out of a treatment program go to a shelter or the streets upon their exit,” Mandelman said. “We’ve got to do better than that.”

They recommend creating a fund to provide housing subsidies for people who voluntarily enter treatment, helping people find housing before exiting residential treatment, and helping those in recovery defend against evictions.

Though Breed is already acting on a few of the recommendations, she said the next steps her office will take will be to carefully review the rest of the recommendations made by the task force and determine which ones will move forward.