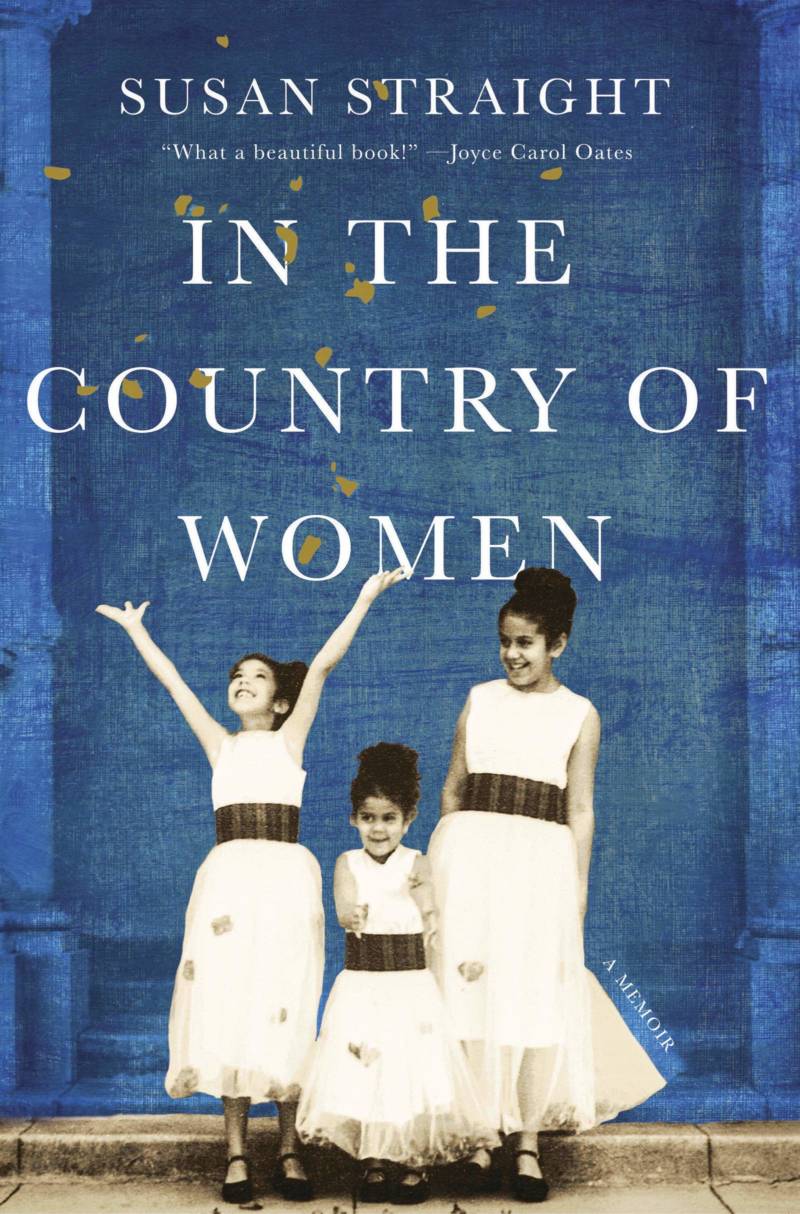

Author Susan Straight's new memoir, "In the Country of Women" — her first foray into nonfiction — celebrates the orange groves, tumbleweeds and driveway barbecues of Riverside and the Inland Empire.

A Love Letter to 6 Generations of Strong Women in One Multi-Racial Family

Straight's memoir honors six generations of women in her multi-racial family, offering a history lesson about the violence they endured, and their tenacious pursuit of the California dream. A professor of creative writing at UC Riverside, Straight was born and raised in Riverside — her family's “promised land." She joined The California Report Magazine host Sasha Khokha to discuss her literary love letter to her three daughters, and to the place she still calls home.

Here’s an excerpt of that conversation:

On writing about violence:

In fiction, you’re taking things that might frighten you, but you’re writing about them in a fictional lens through imagination. I wrote this memoir about real women like Fine, my father-in-law’s grandmother, and the violence she endured from the time she was orphaned at five years old. She was being beaten every day, [after she was] given away just post-slavery to a white family.

Daisy Carter was my daughters' great-grandmother. When Daisy was five years old, she was walking with her mother on a dirt road in Sunflower County, Mississippi. Her mother saw a car speeding toward them and she knew what was going to happen. She threw Daisy up into the ditch, and was hit and killed as the car left. Daisy, at five, was left orphaned.

Daisy, who was very beautiful, went on the road as a dancing girl. Each man she met must have been extremely frightening and violent. She had four daughters with four different men. She was married and each time she fled. Eventually she arrived in Calexico, California in 1936 with four beautiful daughters and she never told anyone who their fathers were.

[I also wrote] about my own grandmother, who I never met. She died at 50 and I wasn't born yet. She endured a lot of violence at the hands of my grandfather. I think about what violence means now, and looking at the way young women are still treated.

I think it’s different for girls my daughters' age; you have online harassment and bullying. We had people leaning out of the window of a car and yelling at us, trying to grab us and throw us into a car. But it feels very fraught. It’s all the same thing, considering the danger of what it means to be a woman in this world.

On her mother:

My mother came here from the Alps of Switzerland and worked in the fields on a farm when she was 15 years old. When her father and stepmother decided they were going to go to Florida, my mom ran away. She went to work for a family as a babysitter, and at night she worked in a diner that served the Oshawa GM Plant.

Eventually, my mother ended up living on her own in Riverside. She taught herself perfect English by listening to Vin Scully do Dodgers broadcasts; today I listen to Dodgers games on the radio and think about my mom wanting her enunciation to be perfect. My mom went back to junior college when she was 40 and I was 12. It was a big deal watching her get her A.A. degree. I was really appreciative of the fact that she was very tenacious as a woman.

On writing about race:

At our family reunion, there were 100 people and I was the only white person. People always tell jokes about white people around me. They say, “We forgot about you.” I think for my kids, the most important thing is that we have this giant family on both sides. In the crucible of our family, race is lesser than family loyalty and survival. I wrote [the book] as a letter to my three daughters because I wanted them to know how proud I am of their heritage.

An excerpt of Straight's memoir:

“In the country of women, we have maps and threads of kin some people find hard to believe. The women could not have dreamed that in this promised land we would still have bullets and fear and murder. Fracture and derision and assault, sharp and revived. I was born here, and I am still here, and I didn’t leave, which doesn’t feel very heroic. You three, my daughters, have laughed at me for looking out the kitchen window of our house toward the hospital where I was born, where your father was born, where you were born. My daily life is a five-mile radius of memory and work and family. You three daughters know this in your genes: You love only orange-blossom honey, because you grew up with that scent and those flowers, that fruit and those bees. You long for Santa Ana winds and sunflowers, tumbleweeds and the laughter of people eating at long unfolded tables in a driveway. We bury descendants of the women, and we serve funeral repasts in church halls built by some of California’s black pioneers. The women in our family are everything: African-American, Mexican-American, Cherokee and Creek, Swiss, Irish and English, French and Filipino, Samoan and Haitian. Some of their heritage remains a mystery.”

On what she learned from having James Baldwin as a teacher:

When I got [to The University of Massachusetts] Amherst, James Baldwin was a writer in residence teaching a workshop. I was stunned because his was one of the first books I ever read at the Riverside Public Library. The first day in class, James Baldwin was so profound, but I was afraid to talk to him. Afterwards his driver and his secretary — they were probably 27 or so and both 6'2"— saw Dwayne, my husband, who was 6'4". They said, “Who’s this? We want to play basketball with him.” After that, the three of them would play basketball, and James Baldwin and I would sit in his rental house and talk about fiction. He talked to me about secondary characters saying, “This is the main part and the heart of your story.”

One night we invited him over for dinner. At the end of the evening he said, “You have to write about home. You must write about this place where you come from.” That changed everything for me. Who we are — and what it means to grow up in a place like Riverside, what it means to be a Californian — was always intrinsically a part of what I wanted to write about.

On staying in Riverside:

There’s a comfort in being someone who can say, “I look out the back window and see the hospital where I was born.” But as a writer who travels around the world, there’s an odd sense that you become a famous writer by leaving home. Over the last five years while I was working on this book, I went to Turkey, Sicily, Salzburg, New York, and San Francisco, and what people wanted to talk to me about was home.

I went home after some of those trips, walked around, and looked at the wonder of the Santa Ana River. Sometimes I run into women who are indigenous; they have a pocket knife and a Tupperware and their grandsons are cutting a specific sage and a specific buckwheat that their great-grandmothers told them help fight diabetes. I can’t think of anywhere I'd rather be than where people have been harvesting the same plants for 20 generations.

On California:

The fascinating thing about Southern California is how many different cities, towns, villages, and communities we have. People think of it as a monolithic place, but if you grow up in El Monte, Ontario, Chino, Riverside, Pico-Union, and Westlake Village, all of it is different.

This is my tenth book, and I have driven to almost every county in California over the last 30 years talking to women, children, people who were homeless, migrant workers in Greenfield working the lettuce fields. All over my state, I find people who are fiercely protective and loyal to the place they’re from, whether it’s Salinas, Buttonwillow, Riverside, Ontario, Pomona, or Chino. I find that no one really understands just how loyal Californians are to their state, but also to their actual homelands inside this large state.