Members of Japanese American communities across California coordinated protests in three cities on Thursday against the imprisonment of migrant children and families at the U.S.-Mexico border, as well as plans to house others in a former internment camp in Oklahoma.

Japanese Americans Speak Out Against 'American Concentration Camps' Holding Migrants

Hundreds turned out in historically Japanese immigrant neighborhoods in San Francisco, San Jose and Los Angeles to highlight parallels between the detention of immigrants today and the incarceration of people of Japanese ancestry during World War II.

In part, the protests aimed to draw attention to a current plan to place migrant children in a detention center at the site of a Japanese American internment camp. The government intends to employ Fort Sill in Oklahoma — which once incarcerated 700 Japanese Americans — as a detention center for about 1,400 migrant children, beginning in July.

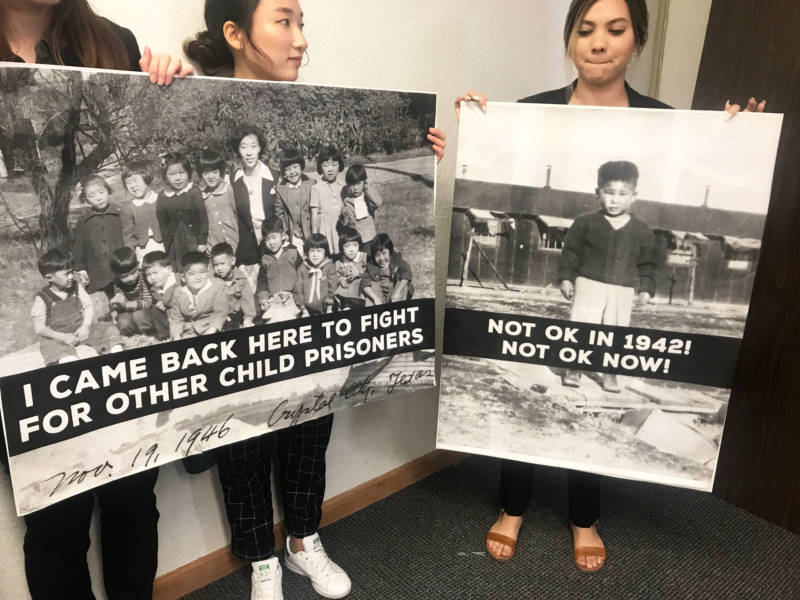

In San Francisco, about a dozen people who'd been put in internment camps attended a press conference, where images of them as children lined the walls.

“The parallels are disturbing, and so resonant with our experience,” said Satsuki Ina, describing current anti-immigrant sentiment.

Ina — who was born in the Tule Lake Segregation Center in Modoc County in 1944 — is an organizer for the advocacy organization Tsuru for Solidarity.

“Once you demonize a collective group of people, then it becomes easier to dehumanize them and do inhumane things to them,” she said.

“This is exactly the same kind of thing that’s happening about the migrants that are seeking asylum, safety and refuge in our country.”

The press conference built on the momentum of Tsuru for Solidarity protests on June 22 at Fort Sill, Oklahoma.

Tsuru means "crane," and the members of the grassroots group folded thousands of origami tsuru as a symbol of the Japanese Americans interned in the 1940s. They brought their collection of tsuru to their protest at Fort Sill last week.

The fort has a long history of detaining groups the U.S. government saw as a threat. In the 1800s, members of the Apache nation were held there as prisoners of war, including Native American leader Geronimo.

In February 1942, two months after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, authorizing the relocation and internment of 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry — two-thirds of them American citizens. That year, Fort Sill became a detention center for 700 Japanese American men.

During Barack Obama's presidency, about 1,200 unaccompanied children were housed there for four months.

Jon Osaki, executive director of the Japanese Community Youth Council, said the Japanese community was abandoned during the years of the internment.

“We stood alone as a community,” he said. “Everybody in our community remembers that, and has sworn for decades that should this ever happen to another community, we would not leave them to stand alone."

Echoing the sentiment was attorney Don Tamaki, a member of the advocacy organization Stop Repeating History!.

“We’ve seen this movie before,” he said. “This ought to never be repeated. This isn’t the American way.”