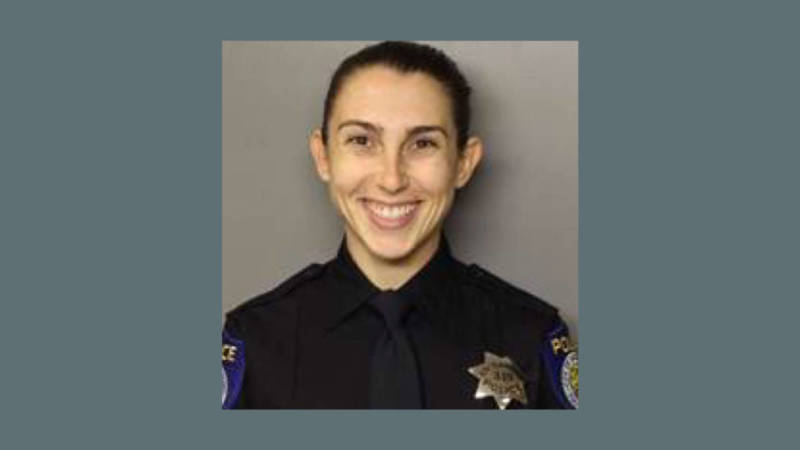

Sacramento County District Attorney Anne Marie Schubert hasn't yet announced whether she'll seek the death penalty for the man accused of killing 26-year-old Sacramento police Officer Tara O'Sullivan last week, but the slaying is a reminder that the politics of capital punishment can be politically fraught — even in solidly Democratic California.

Sacramento Cop's Death Raises the Political Perils of Capital Punishment

Since the 1960s, the politics of capital punishment have at times ensnared some of the state's most storied politicians, including Gov. Pat Brown (who at the urging of his son issued a temporary stay for death row inmate Caryl Chessman) and Gov. Jerry Brown. The younger Brown saw his appointment of anti-death-penalty judges, including Supreme Court Chief Justice Rose Bird, repudiated by voters after he completed his first two terms as governor. Jerry Brown's sister, Kathleen Brown, also struggled with her position on the death penalty, stumbling during her unsuccessful run for governor in 1994.

The question is, will Gov. Gavin Newsom, who issued a sweeping moratorium against executions in March, also pay a price for his opposition to the death penalty? Or, since he isn't on the ballot until 2022, will he be insulated from a backlash?

"He really is very, very good at seeing where political opinion is going to be a half an election cycle or a cycle and a half away, positioning himself as the brave one because he took that step," said Loyola Law School professor Jessica Levinson, referring to Newsom's early support for same sex-marriage and the legalization of recreational marijuana.

"It leaves the impression that it wasn’t popular at the time but he made the right decision anyway," Levinson added.

Sacramento police Officer O'Sullivan was allegedly shot and killed by Adel Ramos as she responded to reports of a domestic disturbance at a North Sacramento home on June 19. Schubert, the Sacramento County district attorney, is a strong proponent of capital punishment and was critical of Newsom when he halted executions in California.

"He essentially just kicked the victims to the curb," Schubert told KQED in April after the governor's decision.

She added, "I'm also bothered that the promise was made by the governor in running" that he would honor the will of voters, who had recently rejected a ballot measure to end capital punishment in California.

But Michael Rushford, president of the Criminal Justice Legal Foundation in Sacramento, which supports the death penalty, thinks there could be a price to pay.

"Newsom's not running again until 2022 and two years is a lifetime in politics," Rushford said. And yet he sees support for capital punishment remaining steady, at least for crimes like killing a police officer.

Referring to Kamala Harris's first run for California attorney general in 2010, Rushford thought her Republican opponent, Los Angeles County District Attorney Steve Cooley, could have won that election "if he used her opposition to capital punishment to bludgeon her with. But he did not. That was the best thing going for him," Rushford said.

A recent poll by Berkeley IGS found voters have very mixed feelings about the death penalty. While registered voters narrowly supported Newsom's ban on executions by 52-48%, a solid majority — 61% — oppose eliminating the death penalty altogether.

Berkeley IGS pollster Mark DiCamillo said while support for the death penalty has softened somewhat over time, Californians are inclined to keep the ultimate penalty for the worst crimes.

"The very heinous crimes are the ones the public has in mind for these special circumstances," DiCamillo said. "Cop killers would certainly be in that category."

When Newsom ordered a moratorium on executions in March, he argued that "our death penalty system, by all measures, is a failure." He also cited ethical and fiscal issues that justified halting executions.

He won strong support from most fellow Democrats, including Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon and Senate President pro Tempore Toni Atkins (D-San Diego), who applauded Newsom's "courage and conviction" in putting a halt to executions.

But not all Democrats agreed. Newly elected Orange County state Sen. Tom Umberg, a former prosecutor, was troubled by Newsom's decision.

"There are some criminals who are so depraved, who have committed such heinous crimes in the eyes of the law and the public, and who are guilty without a doubt, that they deserve the ultimate punishment," Umberg said.

Republicans were also quick to pile on. A group of five Republican state senators introduced a resolution condemning Newsom's action — a symbolic move that's gone nowhere in a chamber dominated by Democrats.

At the same time Assemblyman Marc Levine (D-Marin) introduced a constitutional amendment, ACA12, to place before the voters yet again the question of whether to abolish the death penalty. The measure is in the Assembly Public Safety Committee, but there have been no hearings or votes and it will require two-thirds support in both chambers to make it to the ballot in 2020.

But pollster DiCamillo isn't sure the public is ready to eliminate the death penalty, even in a presidential year. "It would also inject the death penalty into other races, including the presidential race," said DiCamillo.

"It could be used as a wedge issue in congressional races," he said, adding that "the death penalty might work against the interests of some Democrats to hold onto their seats in purple districts."

In 2016, 54% of voters rejected Proposition 62, which would have abolished the death penalty. And in the recent Berkeley IGS Poll, 53% of registered voters said they'd still oppose abolishing the death penalty and replacing it with a life sentence.

The long-term trend of opinion in California has been shifting against the death penalty. But the state is still very divided. The climate is shifting nationally as well, and many of the Democrats running for president say they oppose capital punishment, including Sen. Kamala Harris.

Taken together, it's unlikely that Newsom will pay the kind of price that cost Pat, Jerry and Kathleen Brown political support — or even the backlash Harris experienced after she declined to seek the death penalty for the killer of a San Francisco police officer in April 2004, just months into her tenure as San Francisco district attorney.

But the murder of a young police officer in Sacramento is a reminder of how quickly individual crimes can change the political atmosphere around the issues of policing and criminal justice.