A

s the number of families seeking asylum at the U.S.-Mexico border grows, the Trump administration is contemplating the detention of more parents with their children while they wait to go before an immigration judge.

A new directive by U.S. Attorney General William Barr that takes effect in July requires U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement to detain all asylum-seekers for the months, or even years, it takes to decide their cases.

It’s not clear how the change in policy will be applied to families, whose children are protected from lengthy detention under a decades-old legal agreement.

Most of the families currently arriving from Central America are being released into the U.S. and given a notice to appear at an immigration court. A small minority — 627 mothers and children — are being detained together, according to an official with ICE; nearly all of them are being held at the South Texas Family Residential Center.

Most Migrant Families Detained in Rural Texas

The facility next to the rural city of Dilley can hold up to 2,400 mothers and their children and is the largest family detention center in the country, but it has come under scrutiny as inspectors and detained families report instances of inadequate care.

ICE refused KQED’s request to tour the facility to speak with staff and detainees.

From the outside, all that’s visible from the highway turnoff are the tops of large tents and numerous light poles.

Katy Murdza, an advocacy coordinator with the Dilley Pro Bono Project, who helps families detained at Dilley, said the detention center’s floodlights are so bright, there’s a glow a mile away from it at night. Some of the mothers she has spoken with have complained that the lights, which are never turned off, make it hard to sleep.

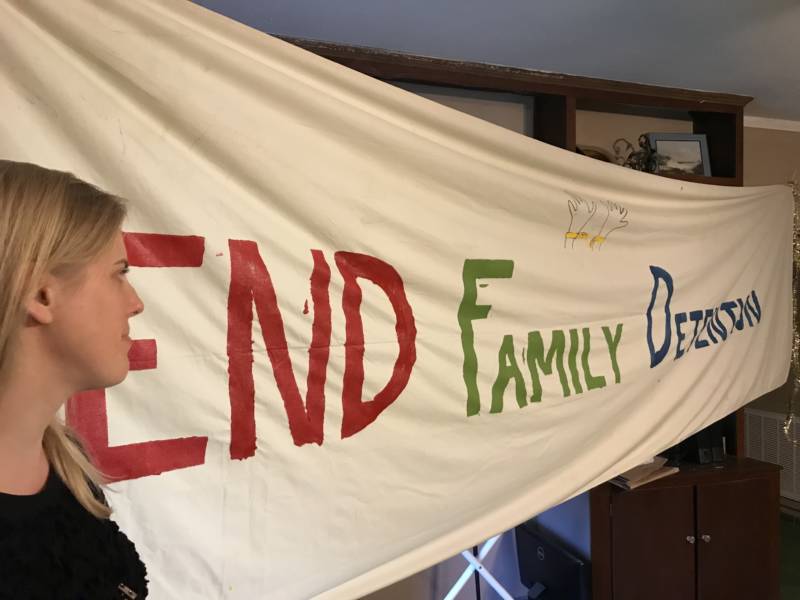

The nonprofit Dilley Pro Bono Project helps families prepare for the first hurdle in the asylum process: convincing U.S. authorities they will be persecuted or tortured if they return to their home countries.