A

t over 300 feet tall, the bell tower at UC Berkeley is hard to miss. On a clear day, it’s even visible from across San Francisco Bay.

Kate Groschner, a Cal materials science doctoral candidate, asked Bay Curious to look into a rumor she’s heard about the tower: that it’s a massive storehouse for dinosaur bones.

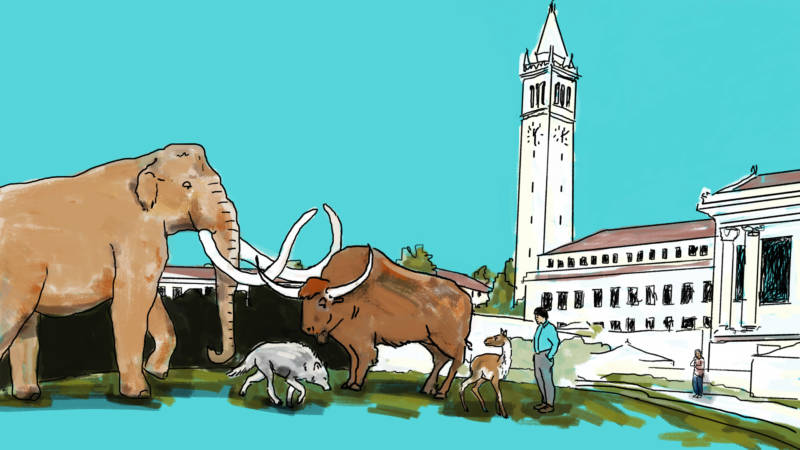

“It’s always dinosaur bones,” says Pat Holroyd, feigning exasperation. She handles Vertebrate Collections for the UC Museum of Paleontology. Leslea Hlusko, a professor in the department of integrative biology, interjects: “But it’s actually better … dire wolves!”

In case “Game of Thrones” led you to believe otherwise, dire wolves were real. An upsized relative of modern gray wolves, they roamed the Americas, including California, before going extinct around 10,000 years ago — which makes them old, but nowhere close to the age of dinosaurs.

What’s known as Sather Tower — or the Campanile, an Italian word for bell tower — boasts several floors packed with not just dire wolf skulls but also tiny shells, bird bones, pieces of whales and prehistoric buffalo. There’s even part of an ancient, toothy swimming reptile called hydrotherosaurus. (Sorry, fossil fans: While the observation deck at the top of the Campanile is open to the public, the floors housing old bones are not.)

So how did so many old bones end up in the university’s bell tower?

“The fossils that are here in the Campanile are primarily from the La Brea Tar Pits [in Los Angeles],” Holroyd explains. At that site, underground tar bubbled to the surface over thousands of years, sometimes trapping and preserving wildlife. (If you’ve ever visited the museum in Los Angeles full of mammoths and saber-toothed cats, you’re familiar with this.)

In the early 1900s, not long before the Campanile was built, Berkeley paleontologists like John C. Merriam excavated the tar pits, and began hauling back curious bones from the likes of extinct horses and ground sloths. Researchers needed to store them somewhere. But around this time, Holroyd says, the paleontology department was moved to a smaller building.

“They said, ‘What are we going to do with all our fossils? We need to have them here; they’re active study. Could we use that empty space inside the Campanile to store the fossils?’ ” says Holroyd.

It turned out to be an ideal arrangement.

“There’s not a lot else that could be housed there without significant renovations to the Campanile itself,” she says.

Indeed — the middle floors of the bell tower feel like an old garage, with low industrial lighting, concrete floors, exposed girders and the distinct smell of old bones that were once covered in tar, and later cleaned using kerosene.