Mia Kagianas thought she’d be out of college and on her way to an MBA by now. Instead, she’s in her fifth year at Sacramento State.

Working to pay for school, dropping classes to save money on her out-of-state tuition, and struggling to get a spot in classes she needs to graduate set her back.

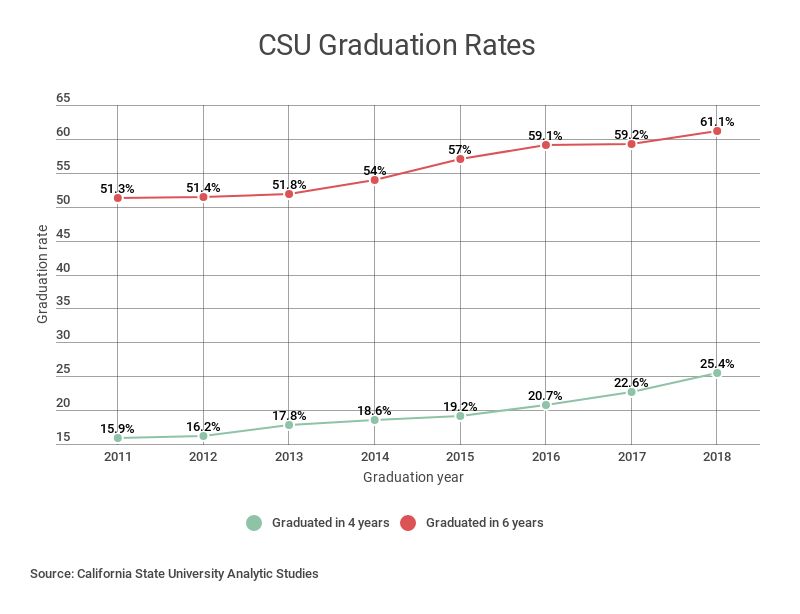

Kagianas’ experience has become the norm at California State University campuses. Three years ago, fewer than 1 in 5 freshmen at CSUs walked away with a diploma after four years.

In response, CSU in 2016 began a major system-wide push to boost graduation rates, and university officials are touting new data released Wednesday they say marks an all-time high for the system: In 2018, over 1 in 4 freshmen graduated in four years — a 32 percent improvement from 2015.

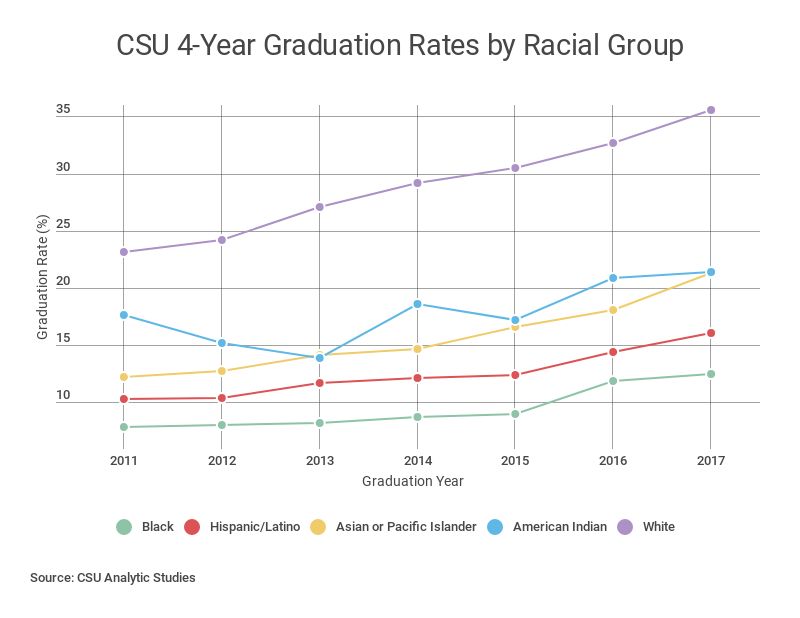

The preliminary numbers, made public during a gathering of CSU officials in San Diego, show the two-year graduation rate for transfer students is also up, by 23 percent. And the gap in graduation rates between underrepresented students of color and their peers narrowed by 14 percent since last year.

Those increases might look small to some, but James Minor, who heads up CSU’s Graduation Initiative 2025, said: "Those percentage point gains translate into thousands of Californians, thousands of CSU students who will earn a degree who otherwise may not have, and that is a tremendous accomplishment."

Those increases might look small to some, but James Minor, who heads up CSU’s Graduation Initiative 2025, said: "Those percentage point gains translate into thousands of Californians, thousands of CSU students who will earn a degree who otherwise may not have, and that is a tremendous accomplishment."

CSU officials are hoping its efforts to get more students graduating on time will help abate a growing capacity crisis.

Last year CSU turned away a record high of more than 30,000 eligible applicants, in large part because there simply wasn’t enough room for them. Some of those young Californians are leaving the state and may never come back, a trend that could cause a potential shortfall in educated workers that experts warn may have dire economic consequences for the state.

But turning the tide is an expensive undertaking. To raise the four-year graduation rate to just 40 percent by 2025, CSU estimates it will need $450 million from the state. Sacramento funneled $75 million into the initiative last year, and CSU plans to ask for another $75 million next year.

CSU Chancellor Timothy White said it’s worth it. “These data demonstrate that sustained investment in the CSU is producing good results, and with additional financial support from the state, we can maintain this positive trajectory for students,” he said in a statement. “I am extremely proud of the remarkable efforts and commitment from students, faculty and staff to achieve these gains."

Minor credits the infusion of state money for making the gains possible, but said there has also been a sea change in how CSU thinks about student success.

“A decade ago if a student came to college and left after a year we would have said, ‘Maybe they weren’t ready, they weren’t serious about getting a college degree,’ ” Minor said. “We now ask the question, 'What is it that we might change about the institution that would enable them to be successful?' ”

To identify those institutional changes, he said, CSU has relied on data and input from students. Among the most common complaints among students is that they can’t get the courses they need when they need them.

That was Kagianas’ experience. During her first few years at Sacramento State, she said she ran into “bottleneck courses” — prerequisite courses where demand exceeded supply.

Kagianas, who is now president of the California State Student Association, said she's noticed her school has taken a more intentional approach to deciding which classes are offered, especially for popular majors.

“We have seen that students feel more confident,” Kagianas said. She's also noticed fewer students "crashing courses,” referring to when students show up at the beginning of the semester in the hopes that someone else doesn’t.

Students now use an online system called Smart Planner to map out their path to graduation with an adviser. It helps students plan, but also assists the university in anticipating which courses it needs to provide, and when.

Minor says this emphasis on better student advising, and streamlining course offerings is key to Graduation Initiative's success. Across the CSU system, he said, campuses have also hired more faculty to make sure classes are available when students need them.

But California Faculty Association President Jennifer Eagan sees a problem with that.

“The majority of the new classes that are being offered are being taught by part-time, temporary faculty,” she said, noting a steady increase in the number of temporary lecturers CSU has hired in recent years.

While Eagan said she's heartened to see graduation rates rising, she's also concerned campuses will feel intense pressure to get students out in four years, even if it's not always in their best interest.

“We know at the CSU a tremendous number of our students work, and work much more than part time,” she said. “Four years might not be a realistic target for all of those students.”

For his part, Minor argues that kind of thinking is bad for students. “I resist and reject a philosophy that says our students are too broke, too poor, too hungry, or work too much to graduate in four years,” he said. “If you give students good information and you give them an opportunity they will prove time and time again that they can actually do it.”

While Kagianas is glad CSUs are focusing on helping students graduate on time, she said the university can’t help its students succeed without ensuring they can also manage food and housing costs, for which limited state aid exists.

“I can’t separate my financial well-being from by ability to take courses,” she said.

Supporting students who struggle with housing and food insecurity, and providing mental health services, is the most important thing CSU can do to support its students, said Kagianas.

CSU does have a number of programs aimed at helping students with these issues.

“That way, students can feel empowered to succeed in their classes without having to worry about all the other aspects of their education that might be barriers to their success.”