The stronger and longer-lasting winds are a result of a particularly strong, particularly cold high pressure ridge sitting east of the rockies. As the wind travels from that area of high pressure across the Great Basin towards areas of low pressure along California’s coast, the wind speeds up, compresses and slams into Southern California.

The question of whether the intensity and duration of the current Santa Ana winds have been impacted by climate change is still up for debate, according to Alex Hall, director of the Center for Climate Science at UCLA.

Hall said there’s research supporting both the idea that the Santa Anas will increase in strength and frequency, as well as decrease, as the climate warms. Part of the difficulty of anticipating what’ll happen to the Santa Anas is that the modeling scientists use to anticipate changes around the world struggles to simulate regional circulation patterns, Hall said. That includes the Santa Anas and ridges of high pressure off the coast of California that are associated with a lack of rain.

But Hall’s confident that the relative humidity of the Santa Anas will fall as things get warmer due to climate change, which doesn’t bode well for fire risk as the dryness of the winds is a major contributing factor to the spreading of wildfires.

Precipitation

A lack of rain is another reason these major wildfires have spread so quickly.

“In a warmer climate, you have a greater contrast between wet and dry,” said Hall. “In the future, we anticipate increased variability in precipitation. So, more precipitation in wet years and less in dry years.”

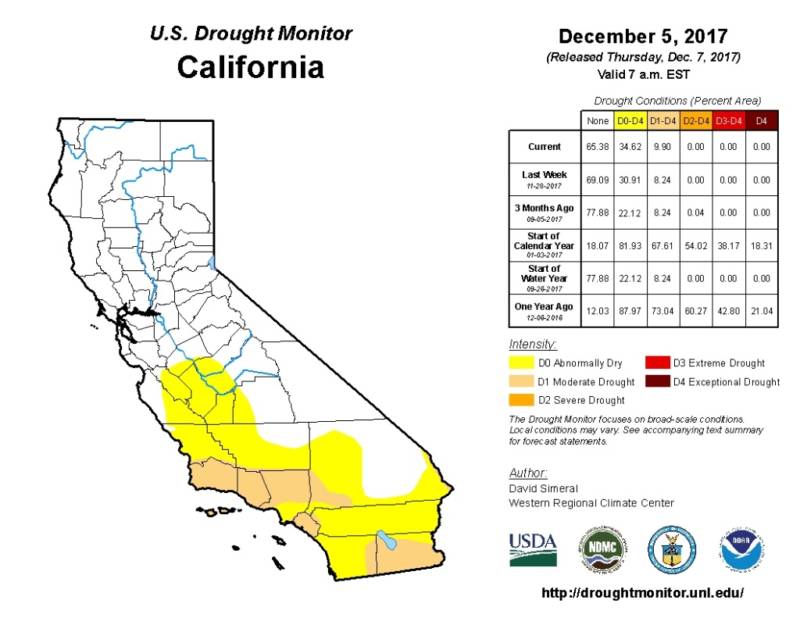

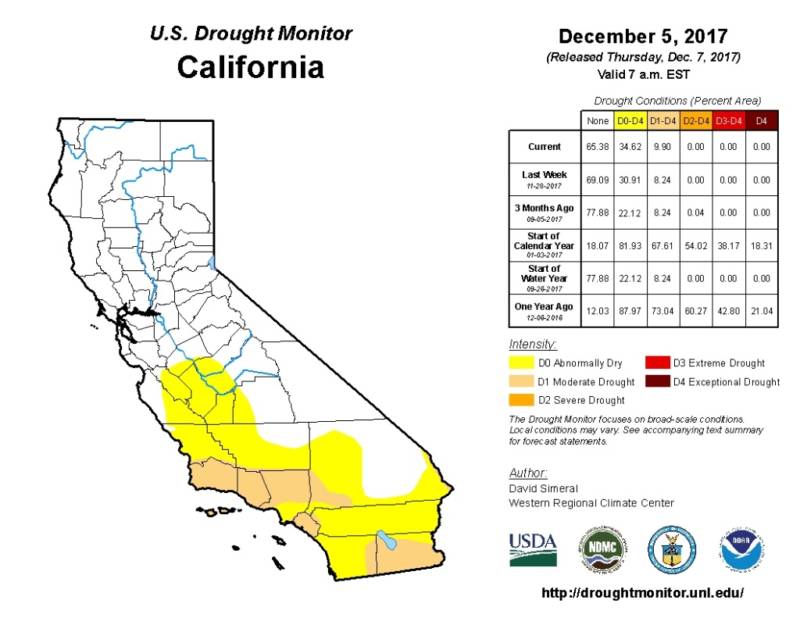

Between 2012 – 2016 California was riddled with extreme drought. Droughts in and of themselves aren’t uncommon, but the our most recent one was likely made worse by human caused climate change, according to a paper written by A. Park Williams, a climate scientist at Columbia University.

Although this past winter felt particularly wet, that was likely because it followed years of drought. In reality, we experienced an average to slightly above-average amount of rain, mostly in January and February. For most of California, drought conditions were alleviated. However for Ventura County, the location of the Thomas Fire, a moderate drought remains.

It’s widely accepted that along with climate change we’ll experience extreme dry periods, punctuated by short, extreme periods of precipitation.

Following our deluge of rain and snow earlier this year, things have since been hot and dry.

“For the last six months say, we’re running both above average temperature-wise and below average precipitation-wise here in Southern California,” said Swain. “In the short term there has been a trend towards a lot more dry years in Southern California. The question is how sustained is that going to be.”

There’s been no rain in Los Angeles so far this season.