“The (corrections department) should be able to begin use of the protocol that it’s already established, which means that execution dates can be set,” said Kent Scheidegger, a Sacramento attorney who helped write Proposition 66, and whom The Atlantic once called “Mr. Death Penalty” for his advocacy on the issue. “I’m sure it will be an intensely fought battle. But we’ll certainly make the argument that there’s been far too much delay and courts shouldn’t delay any further.”

If courts allow Proposition 66 to proceed — more action on the suit is expected after election results are certified in mid-December —execution dates would be established after district attorneys seek death warrants from the trial courts. Eighteen of the 748 death row inmates have exhausted all their appeals, making them likely to be executed soonest. They include Harvey Heishman, who raped an Oakland woman and then murdered her in 1979 before she could testify against him; Richard Samayoa, who broke into a San Diego home in 1985 and beat a young mother and her toddler to death with a wrench; and Tiequon Cox, who murdered four Los Angeles family members of Kermit Alexander, the former pro football player who put Proposition 66 on the ballot.

California death row inmates who have exhausted appeals, by location of crime:

[ExhaustedAppeal]

Click on a pin to see the death row inmate and the crime committed. Locations of crime are approximations. (Map: Matt Levin)

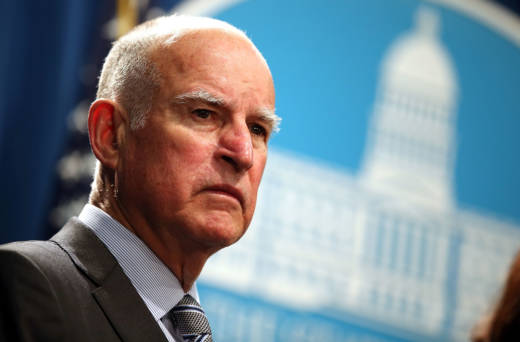

Despite his activism against the death penalty as a young man, Brown never weighed in publicly on the November initiatives.

“I think he just felt he would be compelled to do whatever the voters decide and therefore did not enter into the fray,” said Cruz Reynoso, a former California Supreme Court justice and death penalty opponent.

Reynoso — one of three Brown appointees tossed off the Supreme Court in a 1986 campaign that targeted them for overturning death sentences — said if executions are scheduled before 2018, he wouldn’t expect Brown to block them. “Jerry Brown, like yours truly, may have a moral position,” he said, “but as a public official will enforce the law.”

The governor’s staff declined to answer questions about potential executions. But Brown biographer Chuck McFadden said if executions did resume in his final term, “he wouldn’t like it, not one bit.

“It’s an open question whether he would say anything publicly decrying the execution. … But he would certainly be unhappy about it, even though he’s a far different person today than he was in 1960.”

In that year Brown famously lobbied his father, then-Gov. Pat Brown, to stay the execution of a convicted rapist. Seven years later, the younger Brown stood vigil outside of San Quentin as a cop-killer was put to death inside the prison.

Governors have broad authority under state law to block executions. The elder Brown spared 23 death row inmates by commuting their sentences but allowed 36 to be executed. In his biography “Public Justice, Private Mercy: A Governor's Education on Death Row,” Pat Brown described the difficulty of being “the last stop on the road to the gas chamber.”

“It was an awesome, ultimate power over the lives of others that no person or government should have, or crave,” wrote Pat Brown, who contended that his qualms about it helped Ronald Reagan unseat him in 1966.

After 1967, legal challenges put the death penalty on hold in California for 25 years. Because Jerry Brown’s first two terms as governor (from 1975-1983) came during this hiatus, he avoided the clemency decisions that had racked his father.

Executions in California

[CAExecutions]

As a young governor, Jerry Brown took other actions reflecting his objection to capital punishment—and met resistance. In 1977 he vetoed a bill to reinstate it after courts had abolished it, only to see the Legislature overrule his veto. In 1978, voters re-elected Brown even as they approved an initiative creating the death penalty law still on the books today. Brown appointed justices opposed to executions, only to see voters refuse to retain them.

By the time the state resumed executions in 1992, Brown was running for president—and touting his “uncompromising” opposition to capital punishment.

“When someone is contained in a cage, then to bureaucratically, cold-bloodedly snuff out their life, whether by poison or electrocution or by gas, it doesn’t seem right to me,” Brown said that year.

In 2007 he became California’s attorney general, a position that required him to defend hundreds of death penalty convictions even as the state stopped executions due to lawsuits over lethal injection. It took nearly a decade to produce a new lethal injection plan, a slow process some blamed on Brown.