Mickey Kelley operates the San Francisco Taxi School, which offers prospective cab drivers the courses they must take to get licensed. Classes range from five to 15 students each week. He estimates that from one-third to one-half of his students over the last six months have been former Uber and Lyft drivers.

“It started longer than six months ago, but about six months ago it really picked up,” he said.

Some of those were former cab drivers who had let their licenses expire when they moved on to the ride-service companies but now wanted to return to taxi work, Kelley says.

"We’ve had cab drivers that quit driving a cab [to work for a ride-service firm], and a lot of those guys have come back and had to drive a cab again,“ he said.

Hansu Kim, owner of Flywheel Cab, said he's seen the same thing.

“We’re seeing a stream of UberX and Lyft drivers looking to drive a taxi now," Kim said. "It used to be a trickle, now it’s more of a stream. Not the floodgates, yet.”

Flywheel referred me to Abdallah Hammad, 49, who has been driving for the company for about three years. To supplement his income, he drove on the side for both Uber and Lyft for about a year, but stopped around seven or eight months ago. The main reason: the extra cost and "wear and tear" of using his own car to do business.

(Note: Ride-service drivers can get partial relief from this expense by using the standard mileage-rate deduction on their tax returns.)

Hammad said that twice during Uber calls, customers became angry at the inflated fares they had to pay during a surge pricing period and slammed his car door so hard he had to have his automatic windows repaired.

But hadn't those customers agreed to accept the surge price when they ordered the ride?

“[Passengers] are still mad, even though they know in advance,” he said.

Hammad said passengers who had to fork over during a surge also tended to give him a lower rating. Uber drivers must maintain a 4.6 passenger rating or be suspended from driving.

Kelly Dessaint, 44, who chronicles his adventures as a cab driver for the San Francisco Examiner, started his professional driving career working for Uber and Lyft in 2014. But he quit early last year, went to taxi school, and has been driving for National Veterans Cab in San Francisco since February. He says he likes the feeling of community among cab drivers and that he makes more money driving a taxi than he did for Uber and Lyft.

“You’re doing all these $5 rides, you’re not getting tipped,” he said about driving for the ride services. “With a cab you can talk it up and people will tip you really well.”

Uber doesn’t allow tipping, and Dessaint says "you can tip on Lyft but nobody does. It’s so rare.” (Lyft says passengers collectively gave more than $40 million in tips to its 100,000 drivers in 2015. That's an average of $400 for each driver.)

Kelley, of the San Francisco Taxi School, believes that ride-service drivers who do the math discover that after maintenance and depreciation on their vehicle, they can do better driving a cab, which hasn't always been the case.

"If you go back two years ago, it used to be pretty profitable to drive for [the ride services]," he said. "It’s just not anymore."

A price war between Uber and Lyft has contributed to a decline in driver pay. Michael Banko, for instance, who has been driving for Lyft in San Francisco since 2012, said the lower rates that Lyft now charges have cut his driving income in half. He did say, however, that he gets tips from passengers “all the time.”

How Much Do Ride Service Drivers Really Make?

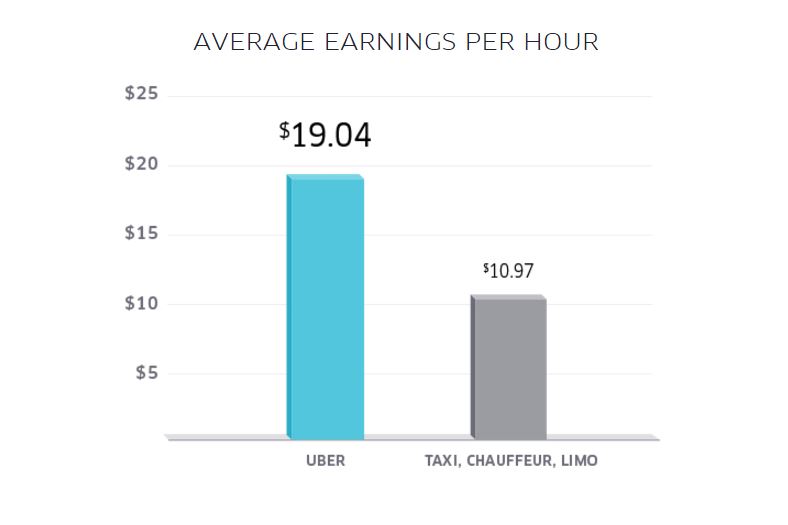

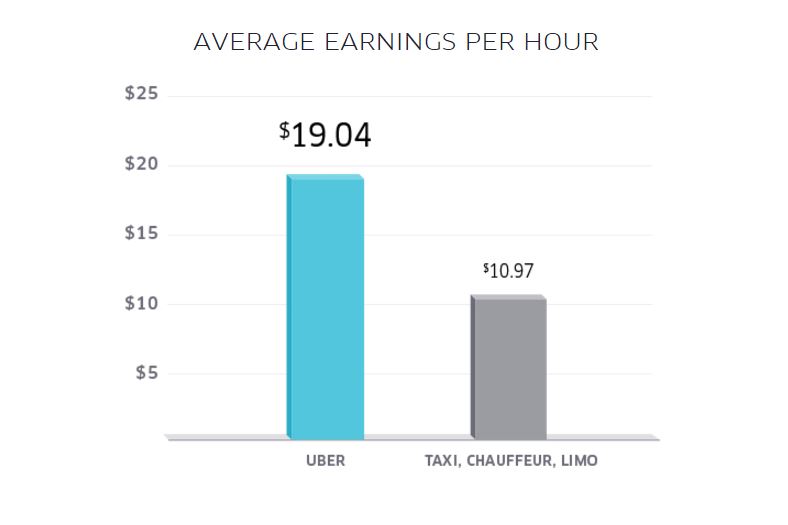

Nobody has really figured out, empirically, whether taxi or TNC (transportation network company) drivers make more money. Early last year, Uber released data that showed their drivers having the advantage.

"A lot of former taxi drivers have decided they wanted to work for themselves and become self-employed,” the company wrote in an April 2015 Uber Newsroom post. "These ex-taxicab drivers are choosing Uber because they like making more money and having a much more flexible schedule.” The post included this graphic:

That $19.04 per hour figure comes from a December 2014 survey by Benenson Strategy Group of 601 Uber "driver partners" in 20 markets. An Uber analysis, put together in conjunction with economist Alan B. Krueger, also cited data in a May 2013 Occupational Employment Statistics Survey by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics to show that taxi and limo drivers in six key markets made a median wage of $12.90 per hour, compared with Uber drivers' $19.19. But the Uber earnings figures do not subtract the cost of gas, insurance and other expenses, like repairs. (Newsweek also noted that Uber price cuts went into effect soon after the survey. )

A similar survey released by Uber last month notably didn't address how much drivers make.

Another data point: In September and October 2015, Sherpashare, a company that helps ride-service drivers track their earnings, surveyed 963 Uber and Lyft drivers. You can see self-reported gross income in this chart.

The data found a big discrepancy in earnings between drivers over and under 55. Those who worked 31 to 40 hours per week and were 55 or under made an average of $2,162 gross per month, while those over 55 made $1,662.

Another SherpaShare study, “based on millions of UberX and Lyft trips tracked by drivers on the SherpaShare platform,” reported the average gross earnings per trip in May 2015 for each company in major cities.

In San Francisco, the average trip earned UberX drivers -- and again, these are gross earnings --- $14.65. Lyft drivers grossed $13.42 a trip.

And yet another set of numbers: Aggregated data for all ride-service trips in California presented at a Nov. 5 meeting of the California Public Utilities Commission and obtained by KQED combine stats submitted by UberX, Lyft, Sidecar, Summon, Wings and Shuddle. It shows the distribution of rides by the amount that passengers paid over 2014-15. Almost half of all fares were under $10, with an additional 23 percent between $10 to $15. A driver's share would be less than that after Uber and Lyft took their cut.

The May 2014 Occupational Employment Statistics Survey found 178,000 cab drivers and chauffeurs in the country made an average of almost $26,000, or $12.35 per hour. In California, the average was $28,190 and $13.56 per hour.

A Former Cab Driver Who Loves Uber

In response to taxi driver Abdallah Hammad's negative experience driving for Uber, company spokeswoman Eva Behrend referred me to current UberX driver Tammy Johnson, of East Oakland.

Johnson, 38, told me she loves working for Uber, after driving for cab companies in San Leandro and Walnut Creek, where she experienced "harassment in different forms. Everyone trying to hit on you."

Financial concerns also compelled her to switch. In general, every time taxi drivers go out on a shift, there's a chance they'll actually lose money, because most of them lease their vehicles from the cab companies. Combine that with the cost of gas, and drivers start every shift in the hole. Johnson says that at least five times she didn't make enough money in fares to cover her daily costs.

She also said there was "too much favoritism. Family members and insiders got the best calls." She felt compelled to buy dispatchers lunch or a bottle of wine to gain favor.

To be sure, the taxi industry has long had a reputation as a place where drivers have to pay cab company employees. The San Francisco Transportation Code prohibits these payments, which some in the industry call tips, and others refer to as bribes, but the rule is unenforced.

While the amounts may seem small, they can add up. For example, John Han, a longtime San Francisco cab driver, told me he switched back to working at Yellow Cab in part because dispatchers at another company, which he didn't want to name, were demanding a total of $10 per day instead of the $6 he had been paying at Yellow.

Drivers are generally split over the fairness of this tipping system -- some don't mind, some say it's onerous. Either way, even $10 a day over the course of a year can easily add up to a couple of thousand dollars in a job that doesn't pay much to begin with. In 2014, one cab driver I talked to told me he was quitting to go to work for a ride service specifically because of having to pay taxi dispatchers.

New Taxi Meters: Leveling the Playing Field?

Last month, California's Division of Measurement Standards approved TaxiOS from Redwood City's Flywheel, a new GPS-based taxicab metering system. That's the same Flywheel that enables passengers to request cabs, track their location and pay, all via smartphones, just like Uber and Lyft.

Flywheel says about 80 percent of San Francisco cabs now accept calls from its app. The requests go out to every taxi that uses the system regardless of which company they work for.

Susan Shaheen, co-director of the Transportation Sustainability Research Center at UC Berkeley, last month told KQED's Mina Kim that TaxiOS, which works with Android phones, will add "an additional layer of flexibility to the taxi industry," allowing fare-splitting among customers and dynamic prices based on demand.

Hansu Kim -- who likes Flywheel's e-hailing system so much he renamed his company after it -- thinks the new TaxiOS meters will further enable cabbies to compete with Uber and Lyft drivers. About 50 Flywheel cabs participated in a recent two-month pilot program of the new meters.

Kim believes the abundance of San Francisco cabs that have adopted Flywheel's convenient e-hailing system leaves Uber and Lyft with the sole advantage of lower prices. He says the new meters will offer his drivers the ability to compete on cost, too.

"With our [new] system we can now go to lower rates, more competitive rates ... where they’re appropriate," he said.

Flywheel -- the smartphone platform, not the cab company -- will create an algorithm that lowers prices when demand is low, Kim said. Those calls will be offered to cab drivers, who can decide whether to take them or not.

Cabs will still not be able to charge more during periods of high demand, as Uber has notoriously done, because the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency has to approve any higher fares. However, Kim says, customers can lure cabs when they appear to be scarce through a pre-tipping component on the Flywheel app.

"A passenger through their app can say I’m going to tip you 10 bucks, or 20 percent, and that creates a tremendous incentive for someone to ... go pick up that fare."

Kim said TaxiOS will also allow him to offer drivers a "split meter system," in which the problem that former cab driver Tammy Johnson described -- leasing a cab and then not making enough money to cover the cost of the rental -- wouldn't be a risk, because the cab company will take only a portion of what the driver makes, the same business model that Uber and Lyft use.

"I need to be able to lease vehicles to drivers who want to drive just a few hours a week part time," Kim said. "So the traditional payment system, where you pay a lease for a cab for a certain amount of time, that needs to change."

The two taxi drivers I spoke to about the new TaxiOS meters were less than enthusiastic, if not downright suspicious.

"Ultimately, the new Flywheel meters are fixing a problem that doesn’t exist," said Kelly Dessaint. He said his customers already split fares and negotiate for lower fares on slow nights. And he considers the algorithmic ability to decrease prices to be a bug, not a feature.

"It becomes a race to the bottom," he said. "And that's how Uber and Lyft screw their drivers."

(Uber has claimed drivers actually make more in some cities under the price cuts.)

John Han, who drives for Yellow Cab, echoed Dessaint's concern.