In November, researchers at UC Berkeley will begin a three-year project to restore and translate thousands of century-old audio recordings of Native California Indians. The collection was created by cultural anthropologists in the first half of the 20th century and is now considered the largest audio repository of California Indian culture in the world.

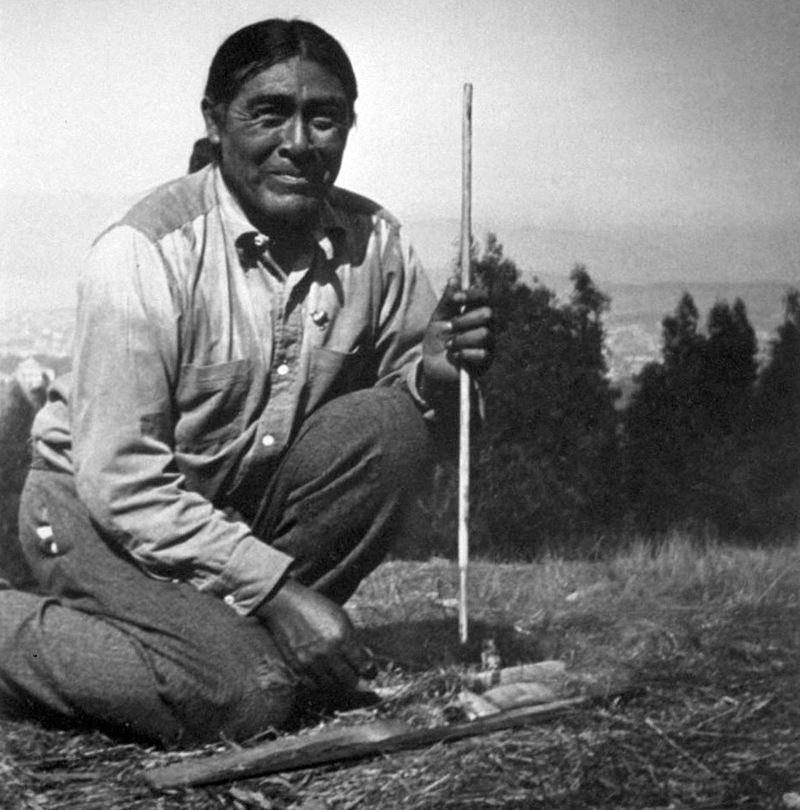

Nearly a third of the 2,713 recordings come from Ishi, the storied last member of the Yahi tribe who lived the last years of his life inside the University of California’s Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology. Ishi died in 1916 from tuberculosis. He was 54 years old.

Five years before his death, Ishi -- desperate, alone and starving -- walked out of the forest and into the little Gold Rush town of Oroville (Butte County). He was the last surviving member of the Yahi tribe, which had been killed off by European settlers. Upon arriving in Oroville, local journalists had a field day, dubbing Ishi the “last wild Indian.”

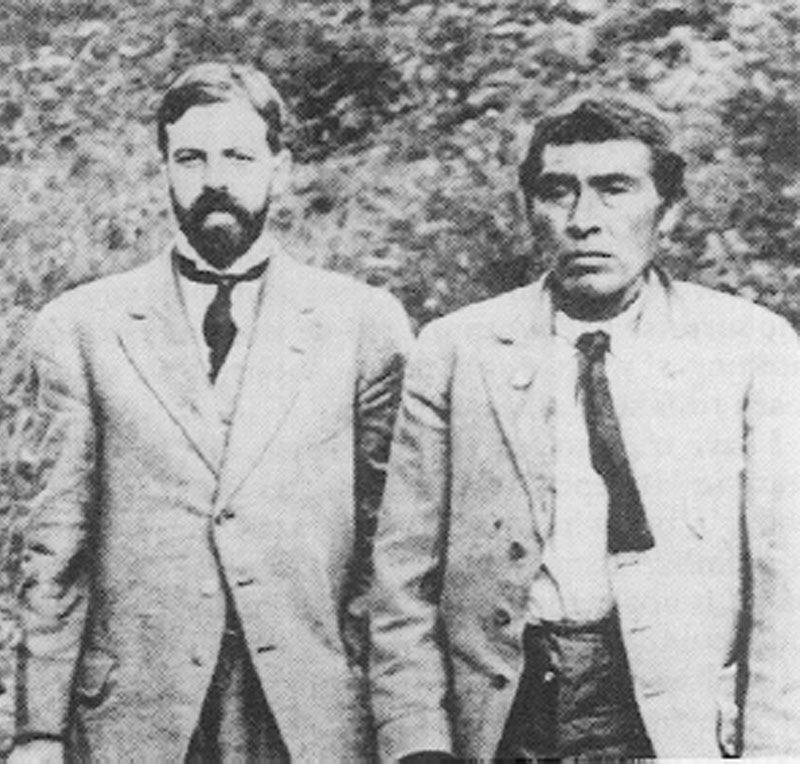

The news quickly reached Alfred Kroeber, a cultural anthropologist in San Francisco who specialized in the study of native Californians. With permission from the Office of Indian Affairs, Ishi was transported to Kroeber at the University of California’s Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology, where he worked as a caretaker. On Sundays, people would flock to the museum to watch Ishi carve arrow points and demonstrate how he lived in the wild.

In September, 1911, Kroeber began using a portable hand-cranked phonograph to record Ishi’s narrations of traditional Yahi songs and stories.

“About the first or second day, Ishi told the story of ‘wood duck,’ this myth that’s not recorded anywhere else in native California,” says Ira Jacknis, the head of research at the museum today and the lead on the UC Berkeley sound restoration project.

“He told the story for hours and hours. And of course he was speaking Yahi for the first time because he had been living alone. So this idea of being isolated and having people encourage him to speak his language was clearly a revelation for him."

While these recordings appear to offer a treasure trove of material for linguists and historians, they are nearly inaudible now due to mold that has grown on the wax cylinders over the decades.

Ten years ago, physicist Carl Haber from the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory created a state-of-the-art machine that can digitally restore damaged recordings. With the help of Haber’s machine, which he calls I.R.E.N.E., academics will soon be able to learn more about Native Californians and the stories they told.

“It’s essentially a big microscope that takes a very, very high-resolution picture of the physical item upon which the sound is recorded,” says Haber about I.R.E.N.E., an acronym for Image Reconstruct Erase Noise Etcetera. “When I say we take a picture, we’re actually making a big topographical map of all three dimensions of the surface of the entire cylinder.” Haber then uses software to analyze and ultimately minimize the noise caused by mold.

Starting next month, Haber’s team will load the entire collection of Native California Indian recordings onto I.R.E.N.E., which will analyze and restore the recordings over the next three years. When the restoration project is complete, the recordings will be sent to tribal descendants, who will determine which parts of the collection can be released to the public.

Kayla Ray Carpenter is a member of the Hoopa tribe in Humboldt County. She's a Ph.D. candidate at Berkeley, and she says the recordings can help keep old traditions alive.

"We have a song ownership system in our culture in which songs are passed down through families," Carpenter explains, "and it might be interesting to connect these people up with songs of their grandparents, their old people."

The remastered recordings will also allow anthropologists like Ira Jacknis to continue to build on the work Kroeber started over a hundred years ago.

“I do see myself as following in the footsteps of Alfred Kroeber to preserve Indian culture,” says Jacknis. “But I’m just a link in the chain, and people who will come after me will actually be able to manipulate the sound recordings in new ways. That was the idea that these anthropologists at the turn of the century had, and we’re just one part of that.”

Special thanks to the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology for use of the original audio recordings of Ishi.