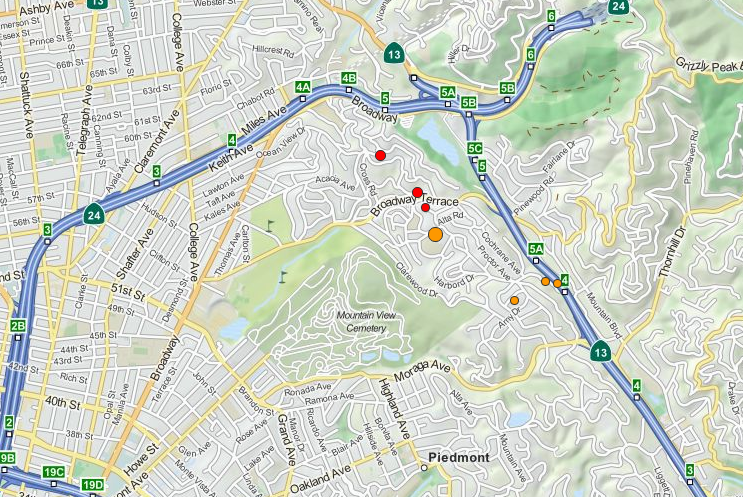

A USGS map reporting the relative intensity of shaking shows the strongest motion in the Berkeley and Oakland hills north and south of the epicenter. The most intense shaking, though, was recorded at a sensor near the west end of Alameda.

For what it's worth, reports from KQED staffers, many of whom jumped onto email immediately after the shake, reinforces the impression that the hardest shaking was felt in a relatively confined area. Most East Bay respondents and some in San Francisco's Mission District said they experienced a good jolt; those who live in Bernal Heights, on bedrock, and further down the Peninsula felt mild shaking or none at all.

David Schwartz, a USGS geologist, said the quake occurred in "an area that has historically had small earthquakes in the magnitude 3 range."

Schwartz noted the Hayward Fault "is one of the most active in the Bay Area. And if you were to look at a map of the seismicity of earthquake epicenters, they pretty much define where the fault is, because the fault is creeping, it's moving slowly all the time, and in doing that it produces small earthquakes."

Anticipating a question about what Monday's temblor might portend -- the Hayward Fault produced an earthquake estimated at 6.8 to 7.0 magnitude in October 1868 -- Schwartz said it's too early to tell until scientists have a chance to pore over data produced by the shake.

"At the moment, it's hard to say that this had any greater meaning than we've had earthquakes in this general area before," Schwartz said.

In May, the USGS published its latest appraisal of the likelihood of major earthquakes on California faults, the Third Uniform California Earthquake Rupture Forecast.

The forecast says says the Bay Area's highest probability of a temblor of 6.7 magnitude or above is on the Hayward Fault, which runs from Point Pinole, north of Richmond, south along the face of the East Bay Hills to Fremont. The new forecast calculates the likelihood of a repeat sometime in the next 30 years at 14.3 percent.