Last October California began a dramatic overhaul of its severely overcrowded prison system. Assembly Bill 109 - known as realignment - had the objective of shedding more than 30,000 inmates from in-state prisons and significantly cutting the prison budget. At the time the law took effect, there were more than 143,000 inmates behind bars in California's 33 prisons. That's almost twice the system's design capacity. Meanwhile, California's Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation received about $10 billion a year from the state's thinning general fund - over 11 percent of last year’s entire spending plan, more than was spent on the University of California and California State University systems combined.

(Teachers: Download our lesson plan to explore this topic further)![]()

So what's happened since last October?

Since realignment began, most “non-serious, non-violent, non-sex offenders” (as defined by the California’s Penal Code) have been sentenced to county jails or put in locally-run probation programs. The program shifts a huge amount of criminal justice responsibility and power from the state to the local level. Prior to last October, every county came up with it's own individualized plan for how it would handle a potential increase in inmates and parolees. Each county then received an allotment of state funding based on its specific plan and the number of new inmates in projected receiving.

What's the goal?

The state was mandated by a court order to cut its prison population by more than 30,000 inmates -- nearly the capacity of the Oakland Coliseum. Again, the new rule mainly applies to inmates convicted of non-violent crimes like drug sales and theft-related offenses.

What about low-level offenders who are already serving prison terms?

They stay where they are. Realignment only applies to parolees and inmates sentenced after October 1, 2011. So contrary to common misconception, non-violent inmates currently in prison do not get transferred to county jails. Additionally, low-level offenders released from prison or jail now get supervised by county-based probation programs rather than monitored by the state’s parole system. And non-serious parole violators generally no longer get sent back to prison: many will serve their terms in county jails. This is where much of the inmate reduction has occurred, because prior to realignment, roughly 47,000 inmates a year served terms of 90 days or less in the state’s prison system.

What’s the difference between jail and prison?

Jails in California are county-run facilities that traditionally house low-level inmates serving sentences of under a year, or for those awaiting criminal trial. Jails are under the jurisdiction of the county sheriff’s department. Every county in the state presides over its own jail system (with the exception of Alpine County, which doesn't have any jails).

Prisons are state-run facilities administered by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR). They're generally intended to house more serious and violent offenders whose sentences are generally over a year. However, in recent decades, an increasing number of low-level, non-violent offenders have been sentenced to relatively lengthy prison terms, and this added to the extent of prison overcrowding There are 33 state prison facilities currently operating in California.

What’s the point of realignment?

The realignment program is California’s response to three major mandates:

1) A state mandate to slash spending

California (as you may have heard) has long been in a serious budget crisis and needs to drastically cut spending. Proponents of realignment, including Governor Brown, contend that counties can manage low-level offenders far more cost efficiently than can the state. California can therefore potentially save a significant amount of money by funding counties at lower levels than what it would cost to house those same offenders in state prisons. State finance analyses estimate a savings of nearly $486 million.

2) A federal mandate to reduce overcrowding

In May 2011, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld a lower court’s order for California to cut its prison population by more than 30,000 inmates.In the 5-to-4 decision, the Supreme Court ruled that conditions resulting from severe overcrowding were in violation of the Eight Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, which prohibits cruel and unusual punishment. The decision was based largely on evidence of avoidable inmate deaths due to inadequate medical care as a result of overcrowding.

3) A societal mandate to reform a “broken” system

California’s prison system has long been rife with problems and inefficiencies. Along with severe overcrowding and outdated facilities, the system has one of the highest recidivism rates in the nation; as of 2010, more than 67% of those released returned to prison. Proponents of realignment assert that much-needed reform and innovation is more likely to happen on a county level, where local officials have greater flexibility to employ programs that reduce recidivism and increase public safety, and where inmates, upon release, will be closer to their homes and services.

Which counties have been most impacted?

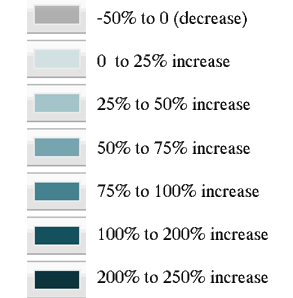

Check out the interactive map below to get a sense of which counties have received the brunt. Parts of the Central Valley have felt the most impact.

It's been less of an issue for most counties in the Bay Area, which have only experienced modest gains in their jail populations. And particularly in the case of Alameda and San Francisco counties, many low-level offenders were already under local supervision before realignment began.

It's important to remember that each county decided its own process for dealing with realignment. So two neighboring counties might have very different approaches in how they handle the changes. Some counties have adopted reforms such as early release for good behavior, shorter sentences, and alternatives to incarceration (like electronic monitoring programs). Other counties, however, have taken a less nuanced approach, and have been placing new inmates in local jails for relatively long-term periods.

Data Source: California Board of State and Community Corrections