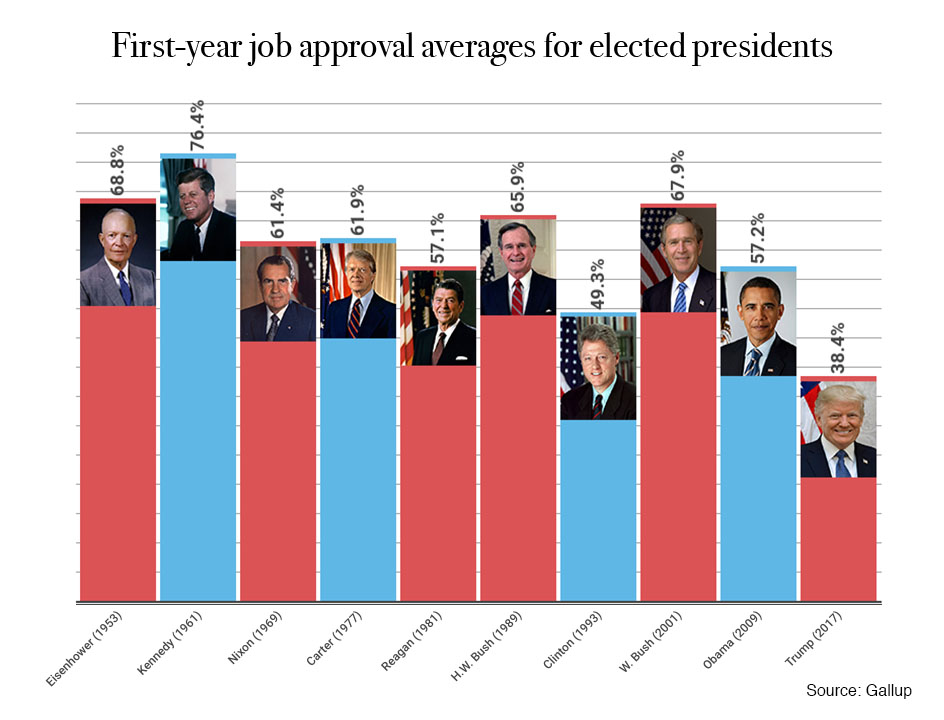

Trump's unprecedented level of unpopularity from his very first day on the job isn't entirely surprising. After all, he was elected president despite losing the popular vote; roughly 3 million more people voted for his opponent, Hillary Clinton. And the ongoing investigation into his campaign's possible collusion with Russia, hasn't done wonders for his popular appeal, nor has his inherently incendiary nature or propensity to attract conflict and controversy.

That's not to say that a president can't rebound from low first-year approval ratings. Take Bill Clinton, whose popularity dropped sharply during his first year in office, but rose fairly steadily thereafter. He left office seven years later with an approval rate of about 65 percent.

As our latest Above the Noise video on popularity in high school explains, there are two main types of popularity in a social context: status and likability. Status refers to someone's power and influence over others, whereas likability is a measure of how much other people genuinely like you. Those with strong status may have a commanding presence, but often maintain only loose, tenuous friendships with others, and may be more prone to isolation and anxiety later in life. Strong likability, on the other hand, yields deep, lasting friendships and results more often in a greater sense of self-worth and more positive social and professional relationships in the future.

Of course, Trump is the President of the United States, not the captain of his high football team, and his approval is determined by much more than just his status (which is pretty strong) and his likability (not so strong). Personality still plays a role in the president's approval ratings, but it's how the public perceives of the kind of job he's doing that really has the most impact.

And low marks aside, Trump has scored some pretty significant victories during his short stint in office and been strikingly effective in dramatically changing the nation's course from the one charted by his predecessor. In just over a year in office, he has slashed many of the environmental and financial regulations established by President Obama, and has appointed industry lobbyists and staunch regulatory critics to head key government oversight agencies.

He has also successfully pushed through an unpopular tax bill that heavily favors the wealthy and guts a key part of Obamacare. And he has helped reshape the judiciary, appointing a staunch conservative to the Supreme Court and placing four times as many federal appeals judges as Obama did in his first year.

All of which begs the question: Does the president's popularity (or lack thereof) really matter?

If history is any guide, low approval ratings early aren't necessarily a death knell, but can certainly come back to haunt a president and his party.

Trump is still the leader of the Republican Party, but lacks the clout of a president with widespread popular support. That means Republican leaders in Congress may become less willing to advance his legislative priorities and more likely to challenge his command.

And then there are the upcoming midterm elections.

Congressional elections are by and large referendums on the president and his party, which almost always loses seats. Historically, the lower the president's approval rating at that point, the more seats lost.

Only two postwar presidents have gone into the midterms with approval ratings below 40 percent: Truman in 1946, when Democrats lost 55 seats, and George W. Bush in 2006, when Republicans lost 34 seats.

None of which bodes well for Trump and his party come November.

Additionally, the president's low approval rating has helped embolden Democrats and has inspired political participation and enthusiasm on the left, as evidenced by the formation of prominent grass-roots political groups, especially ones led by women. Since Trump took office, there has also been a surge of new Democratic candidates and a spike of Democratic voters in special elections.