To that end, the organization is also producing a series of short animated videos, including this most recent piece recounting the 1898 lynching of Private James Neely, an African-American veteran who had recently returned to Georgia after fighting in the Spanish-American War.

I recently interviewed Stevenson about EJI's educational initiatives. Below is a transcript from part of our conversation. Listen to the full interview here.

MG: Describe the goal of this project.

I don’t think we’ve done a very good job in this country of educating people about our history of racial inequality. We lived through an era in America of racial terrorism, where thousands of African-Americans were burned alive and hung and murdered and beaten and mutilated, sometimes in the public square in front of thousands of people, who had the comfort of committing this terror with no risk of prosecution, no threat of arrest or adverse consequences. This period of violence and terror really shaped America’s development.

And we don’t talk about it, we haven’t acknowledged it, we haven’t really explored the implications of it. And so we’re trying to change that. We have projects that are trying to educate people about the terrorism that took place in their communities. We’re trying to put markers at every lynching site in America. I think the landscape is silent about the violence and the terror that shaped our development as a nation in the 20th century, and that has to change.

In other countries, like Germany or Rwanda, you’ll see markers and monuments that identify the spaces where Jewish families were abducted during the Holocaust. Germans want you to go to the Holocaust Memorial and reflect soberly on that history. They’re trying to change their identity. They don’t want to be a nation remembered only for the Holocaust and Nazism and Fascism. They’re trying to create a new identity.

We haven’t really done that in America, particularly in the American South, where we romanticize the past, we glorify the past. So we think that has to change. And one of the ways we’re trying to change that is developing short pieces that teachers and schools can use to educate students about the horrors of lynching. And we’ve put together a report called “Lynching in America,” which documents over 4,000 lynchings, and tries to explain why racial terror lynchings developed, what they involved, who was targeted and why this era is so significant.

If you live in Oakland or San Francisco or Los Angeles, or if you live in Chicago or Detroit or Minneapolis or Boston, you need to understand that the black community in your city came to your community not as immigrants looking for new economic opportunities, but they came to these cities as refugees and exiles from terror in the American South. The legacy of lynching is very directly connected to communities in Oakland and L.A. and San Francisco and others places in the North and West. And I don’t think we’ve made that connection.

For me, the era of terror has profound implications for our continuing struggles, ranging from racial bias in the public sector to police violence. All of it, I think, cannot be understood without understanding this history.

MG: How would you respond to an educator who's hesitant to teach students such an upsetting narrative? Why is it so important for young people to learn that these tragic events occurred?

If I had to characterize the biggest problem we have in this country, I think we suffer profoundly from the absence of shame. I believe we have acculturated a nation into believing that they can do terrible things to other people and you don’t ever have to say I’m sorry, you don’t ever have to learn from it, you don’t actually have to reflect on it.

And I believe many on the challenges we’re facing today in our country are rooted in our failure to acknowledge the mistakes of our past. So I think we’re not going to be a nation that evolves and matures and becomes truly great until we become a nation with the confidence to say (what) slavery was and it burdened us and it haunts us. And I think that our country has been indifferent to a narrative of racial difference that has created a lot of victimization and violence.

I think we’re a post-genocide country. What happened to native people, in my judgment, was a genocide. We killed millions of people and we didn’t own up to that because we said, no, those natives are savages. And we used that narrative of racial difference to justify that violence. And we kept their names for rivers and counties and streams and buildings, but we made the people go.

I think that same narrative is the true evil of American slavery, which we never addressed in the 13th Amendment. I think the great evil of American slavery was the ideology of white supremacy. And if you read the 13th Amendment, it doesn’t talk about narratives of racial difference or white supremacy. It only talks about involuntary servitude. And to me that means that slavery didn’t end in 1865, it evolved. And that’s what gave rise to this terrorism and lynching. And that was followed by segregation and codification of racial hierarchy and Jim Crow. And while we passed civil rights laws, we never confronted the damage that this narrative of racial difference did and continues to do.

And now, the reason why teachers need to teach this history to students is because the black and brown children in their classrooms are going to be burdened with a presumption of dangerousness and guilt. And that presumption will exist for the rest of their lives until we confront this narrative.

And you can’t understand the power of it unless you understand the history of slavery and lynching and segregation. I also think that non-minorities in this country will not create a kind of freedom for themselves until they acknowledge this history. I don’t think any of us are free, to be honest. So rather than thinking that there’s something discretionary about the teaching of this history. I think it’s essential. I think you do a disservice to children of all colors and races and ethnicities by allowing them to be ignorant of the ways in which our country has yet to deal with the history of racial injustice.

MG: How can students walk away from these lessons feeling hopeful and empowered instead of just upset and depressed?

Well, I think that there’s so much evidence that despite the horrors of this history, that we have an incredible capacity to overcome, to survive, to succeed.

I started my education in a colored school, because in my county black children were not allowed to go to the public schools. My great-grandparents were enslaved. My grandmother was in my ear all the time about this history of slavery. So despite the fact that my generational connection to slavery is very short, and that I started my education in a racially segregated school, and that there were no high schools for kids of color when my dad was a teenager, so he couldn’t go to high school.

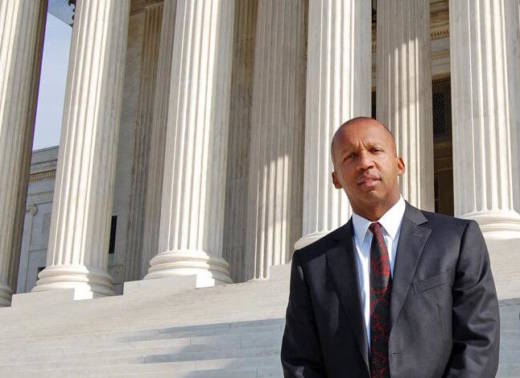

And despite all of that, I had the great privilege to go to college, and to go to law school and to argue cases at the U.S. Supreme Court and to talk to lots and lots of people. And I am standing on the shoulders of those enslaved people who did not give up. Who learned to read despite the violence and degradation of slavery. And chose to have children and raise those children with hope and belief that if they worked hard they could achieve something. I’m standing on the shoulders of people who fled the terror in the American South and found ways to raise families and to create hope for their children.

My parents were humiliated every day by Jim Crow segregation, and yet they persevered. Standing on the shoulders of these people means that I can do so much more. I do civil rights work, I’ve had a lot of challenges. But I’ve never had to say, like the people who came before me, “my head is bloody but not bowed.”

And what that means to me is that I have every reason to believe that we can succeed, that we can prevail. That as they used to sing: “We shall overcome.” And that’s the hope, that’s the conviction. And if you understand its history, and really understand it, with the stories of violence and despair and pain and agony, there’s an unmatched story of perseverance, of hope, of strength, of resiliency.

That story is what ultimately ought to persuade all of us that we should not accept the status quo. We should not accept the presumption of dangerousness and guilt that continues to burden black and brown people in this country. We should not accept the silence that has accompanied our history of racial inequality and racial injustice. That we should demand more because we want more, we expect more.

And that’s ultimately a view that’s rooted in hope. To achieve these things, you’re going to have to be willing to stand up when other people say sit down, you’re going to have to be willing to speak when other people say be quiet, and you do that when you have enough hope to believe that act, that moment, is worthwhile.