Earlier this month, 11-year-old Hannah Bradshaw stood up at a town hall in suburban Salt Lake City, asking U.S. Rep. Jason Chaffetz (R-UT): "What are you doing to help protect our water and air for our generations and my kids' generations?"

The takeaway: town halls with elected leaders can be a pretty solid way to get your voice heard, even if you're still years away from stepping foot inside a polling booth.

At both town halls, Chaffetz and Cotton were drowned out by angry crowds booing loudly and chanting "Do your job!" It's a scene that's played out in Republican town halls around the country this month, as angry constituents concerned about efforts to repeal Obamacare and other Trump administration proposals, have packed into high school auditoriums and community centers to give their representatives an earful.

Both the U.S. Congress and Senate have been on recess this week, and as is customary during legislative breaks, many members return to their home districts and hold town halls with constituents. But this time around, for Republicans especially, the reception has been less than cordial.

Chaffetz, for his part, doubted that many of the people in attendance actually lived in his district, claiming (without evidence) that many were outsiders who had come to "bully and intimidate" him. And President Trump was quick to dismiss the various scenes of upheaval as political stagecraft and not a real reflection of public opinion.

Trump might be correct in his charge that liberal activists have instigated and organized many of these unruly town halls, but that doesn't diminish the potential influence the events could have in Washington.

In fact, they're strikingly reminiscent of town halls held just eight years ago, in the summer after President Obama's historic election victory. That's when conservative activists, livid at the prospect of national health reform and government mandated insurance, shouted down their Democratic representatives. Many Democratic leaders initially overlooked the unrest, dismissing the protestors as paid stooges and extreme outliers. Then-Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) infamously called the demonstrations "AstroTurf," as opposed to any kind of real grassroots effort.

But the well-orchestrated protests gave rise to the Tea Party, whose conservative fervor helped topple Democratic leadership in the House in the 2010 midterm elections and led to a Republican takeover of the Senate four years later. Democrats have yet to recover: today they remain the minority party in both houses as they scramble to resist the sweeping agenda of a new Republican president.

In an age of arm-chair activism, online petitions, and social media echo chambers, the longstanding American tradition of the town hall meeting still remains an opportunity for good, old-fashioned civic engagement, a direct forum for constituents to look their elected officials in the eye and voice concerns loudly and clearly.

Keep in mind that most legislators, have fairly minimal job security. Unlike senators, who serve six-year terms, members of the House face re-election every two years. So except for representatives in consistently safe, reliable districts (like much of the San Francisco Bay Area), most are -- or at least, should be -- constantly measuring the pulse of their constituents.

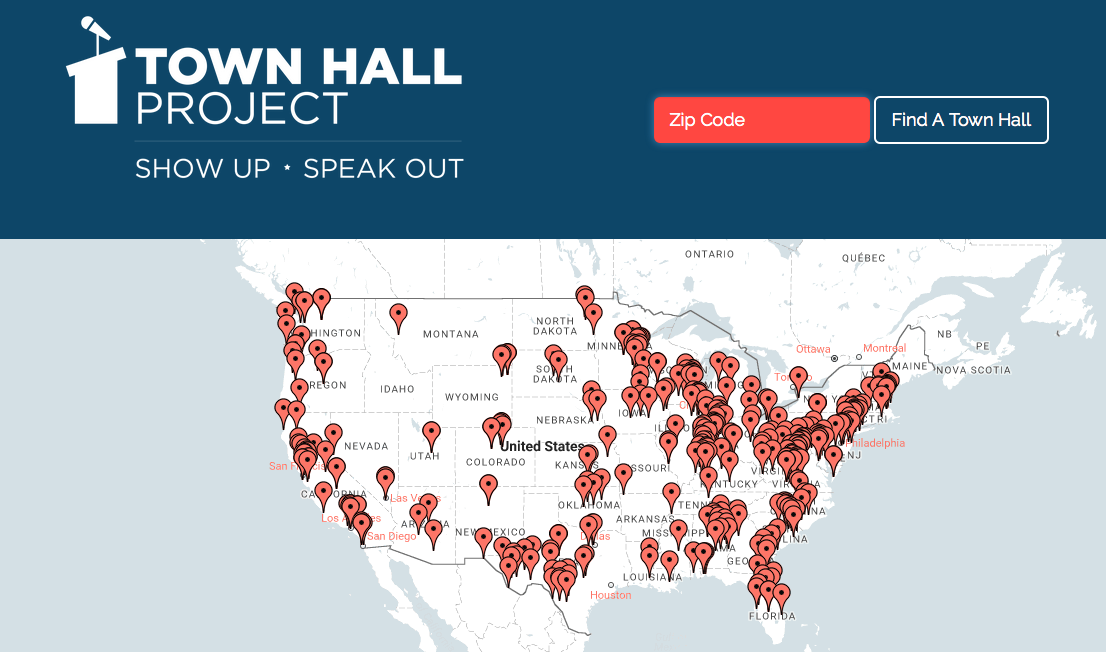

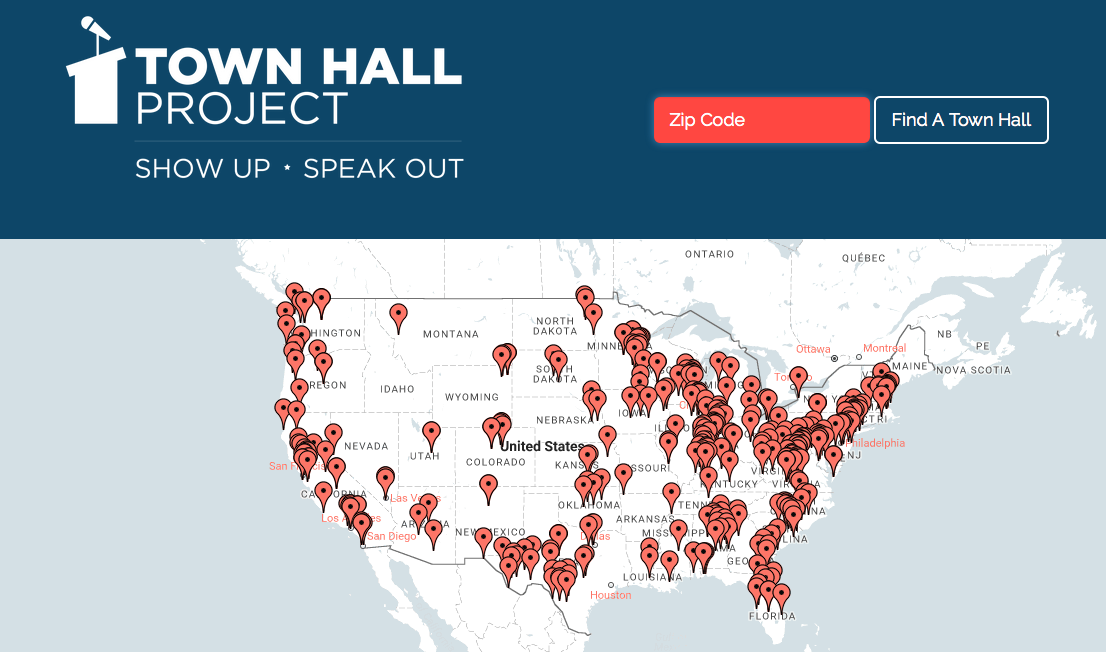

The Town Hall Project, a progressive volunteer group, lists Republican and Democratic congressional town hall meetings across the country, compiled through crowd-sourced submissions. On the site, the group notes that "there is no better way to influence your representatives than in-person conversations ... You have more power than you think."

If you're not sure who represents you in Congress, find out here.