The Supreme Court on Wednesday removed a 40-year-old cap on the total amount of cash individuals can contribute to political candidates and party committees. The latest in a string of rulings chipping away at longstanding campaign finance limits, the court's 5-to-4 decision in McCutcheon v. Federal Elections Commission is expected to let new flood of money pour into America's already cash-saturated political process.

The Supreme Court on Wednesday removed a 40-year-old cap on the total amount of cash individuals can contribute to political candidates and party committees. The latest in a string of rulings chipping away at longstanding campaign finance limits, the court's 5-to-4 decision in McCutcheon v. Federal Elections Commission is expected to let new flood of money pour into America's already cash-saturated political process.

What the decision actually does

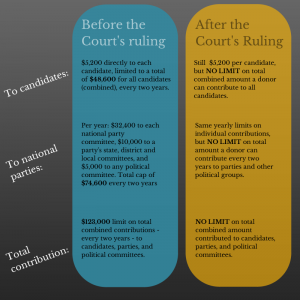

It removes the cap on the combined amount of cash that any one person can directly give to candidates running for federal office, or to political party committees.Although the court maintained the existing cap of $5,200 as the most any donor can directly give to a single candidate, it got rid of the limits on combined contributions.

Up until now, an individual donor could give no more than $48,600 in combined contributions to candidates, and no more than $74,600 in combined contributions to local and national party committees. Combined, $123,200 was the maximum amount a single contributor could give in a two year period. Now there is no limit.

To put that in perspective, let's say a single donor were to give $5,200 to every single House and Senate candidate from one political party in an election with 468 House and Senate seats up for grabs. The total contribution would be $2,433,600. If you've got the money to burn, there's nothing stopping you anymore. A nice infographic in the Washington Post illustrates the new formulas.

To put that in perspective, let's say a single donor were to give $5,200 to every single House and Senate candidate from one political party in an election with 468 House and Senate seats up for grabs. The total contribution would be $2,433,600. If you've got the money to burn, there's nothing stopping you anymore. A nice infographic in the Washington Post illustrates the new formulas.

What was the logic behind the court's ruling?

The five justices in the majority are the usual suspects: the same conservative side of the bench responsible for striking down at least five other campaign finance restrictions over the last eight years, including the landmark Citizens United decision in 2010. In so doing, the court has succeeded in chipping away at many of the election spending reforms from the 1970s that came about in the wake of the Watergate scandal.

Like in previous cases, the McCutcheon ruling was rooted in the majority's strongly held conviction that political money is a form of speech protected under the First Amendment, and that the government should have only a limited role in regulating it.