In an attempt to get the drop in the young adult smoking rate moving again, Dr. Pamela Ling of the University of California, San Francisco's Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education has been working with the Rescue marketing agency of San Diego to establish an anti-smoking brand called “Commune,” specifically targeting the nation's ample supply of hipsters.

What the brand is "selling" is the desire not to smoke.

“One of the challenges around doing public health campaigns is that it’s really hard to sell the idea of not doing something,” says Ling. “If you’re selling cigarettes you can promote Marlboro, but if you’re selling not smoking Marlboro, you’re not really promoting anything. So the idea is creating a brand that competes with the tobacco brand.”

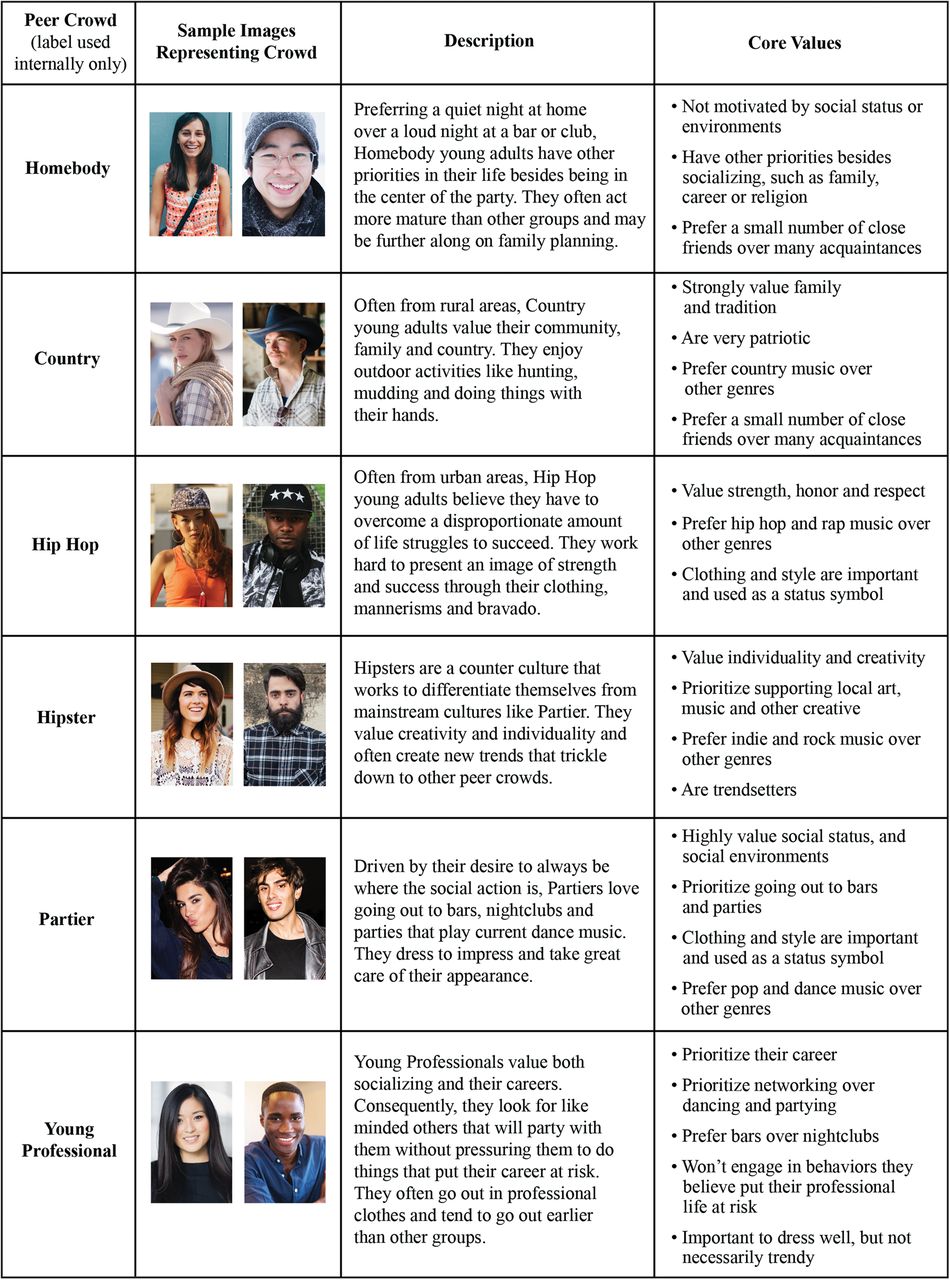

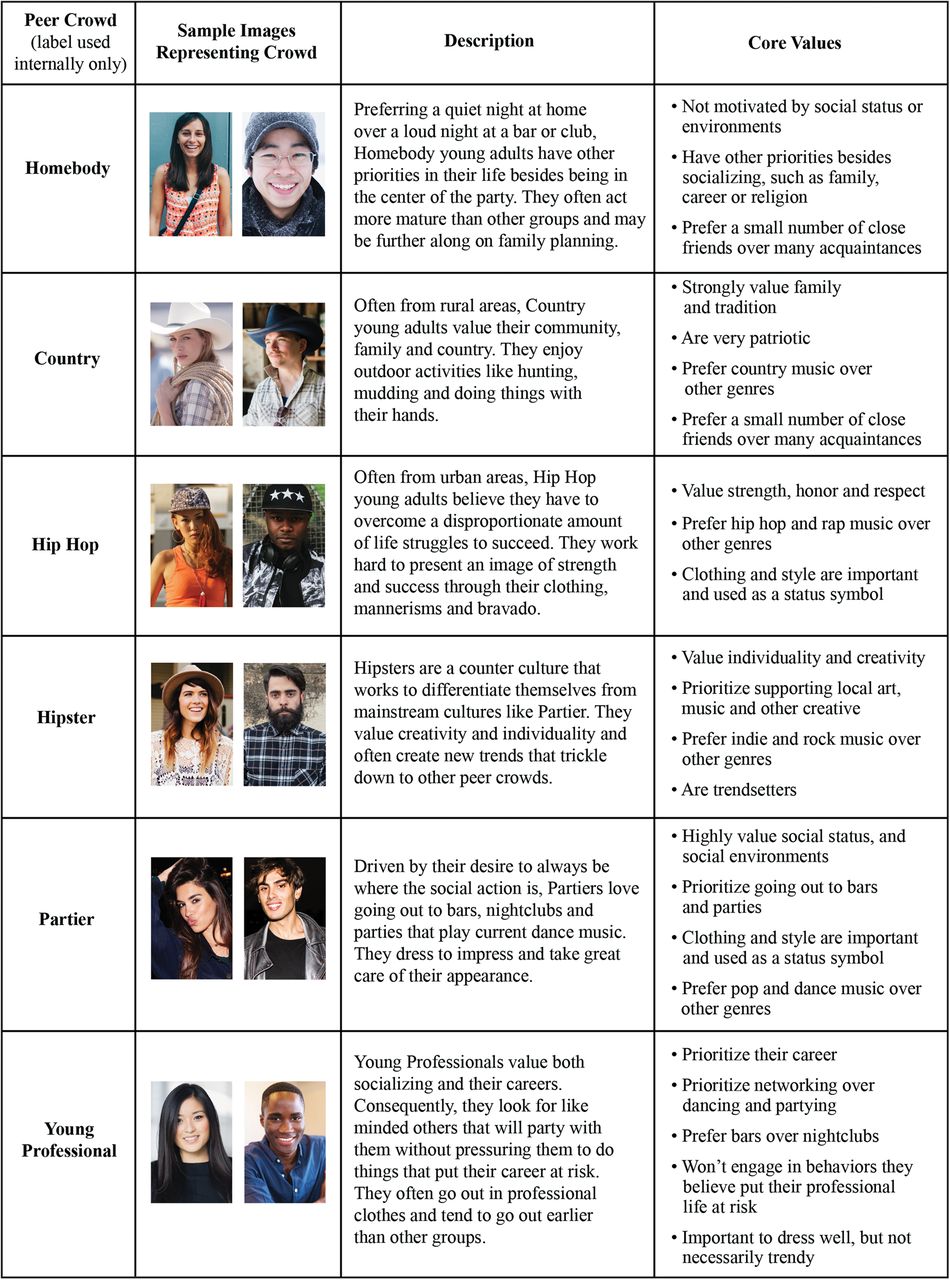

Peer Crowds

To that end, the Rescue campaign has held events under the banner of the Commune brand in hipster drinking establishments in a handful of cities around the country. The lineups feature local bands and artists and the campaigns are currently active in Minneapolis and Duluth. The project ended an eight-year run in San Diego in February and a 3-year stint in San Francisco in June.

The campaigns use a marketing strategy called social branding, which attempts to associate healthy behaviors with the values of individual subcultures, called "peer crowds." In this model, a traditional demographic, such as young adults, is divided into cultural segments with shared interests, styles of dress, values, and media consumption habits. Hipsters were the first target.

“Our goal was to develop something that spoke to them authentically,” says Jeff Jordan, the founder and president of Rescue. “That’s really the value of segmentation. Not only can you concentrate your resources on a higher risk group, minimizing waste, but you can actually make something a lot more appealing and tailored to the group, so they actually listen to you."

The potential messaging power of using peer crowds like hipsters is illustrated in a recent paper by Jordan, Ling and UCSF statistician Nadra Lisha, looking at data from surveys of 3,366 18-26 year-olds, conducted in the watering holes of San Diego, San Francisco, and L.A. The researchers focused on bars because studies have found an association between tobacco marketing there and smoking. From the data, the researchers mapped use of cigarettes, e-cigarettes, hookahs, cigars and smokeless tobacco to six different peer crowds. (A seventh group, LGBT, was added after subsequent studies.)

The researchers found membership in these groups to be a significant predictor of tobacco use on its own, independent of traditional demographics like ethnicity. For instance, while nearly 50 percent of Hispanics in the sample used at least one of the products, the hipster Hispanic rate was 55 percent while the Young Professional Hispanic rate just 39 percent.

Similarly, Jordan, Ling and colleagues found, in a 2013 study of 13 to 20-year-old black youth in Richmond, Virginia, that a Hip Hop peer group smoked at a much higher rate than two other African-American cohorts, called Mainstream and Preppy.

Worth a Thousand Words

Okay--but how do researchers know which peer group to assign each person to?

What makes a hipster a hipster?

The researchers started by showing focus groups images of people with different clothing and hair styles. Individual photos elicited similar descriptions, which the researchers grouped together under different labels, like Hipster, Partier, or "Homebody.

When looking at the photos, "the kind of narrative that people talk about is quite different," says Ling. “So you can say, OK … picture No. 27 is always put in the Partier group; people are talking about how they like to go out and have a good time and they drink beer and like sports.”

Having pegged certain photos to particular groups, the researchers then asked study participants to pick photos of people who “best fit into your main group of friends.” Those rankings were then combined with data from a list of bars the subjects patronized, and voilà -- you have been labeled.

Researchers named one of the peer crowds "Hipsters" because it was a common term of description for certain photos. They don't, of course, use the word with their subjects.

“We don’t usually overtly say hipsters because it will turn off all the hipsters,” Ling says.

Building a Brand

The first intervention started in San Diego in 2008. The researchers picked hipsters as a target because that was the group with the highest smoking rate.

The next step was to create a brand around an anti-smoking message. The name “Commune” tested best.

“The thing that tested well about Commune is the idea that this peer crowd supports each other, whether you’re an artist, a band, a DJ or you have your own little clothing store,” says Jordan.

The project then instituted monthly bar nights and other Commune-branded events, promoting them as a way to support the local community. Local is big with hipsters, according to the research. While taking in the music and art, attendees also got a good dose of anti-tobacco messaging. This was meant to counter tobacco advertising aimed at young barflies by ‘denormalizing’ the companies that sell cigarettes -- tying them to a host of perceived ills anathema to the hipster population.

"We have rejected big corporations for a long time, like Big Music that hinders creative freedom and Big Fashion that runs sweatshops," the Commune website says. "Our stand against Big Tobacco is even more important, since the industry contributes to things like world hunger, deforestation, and neo-conservative policies."

The idea that Commune is trying to convey, says Ling, is that it's "more authentically hipster than, say, Camel, that’s trying to come in here and sponsor tattoo artists and kind of pretending to be hipster, but they’re really not."

"It's kind of a war of ideals," she said.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9dzS1c2HBA8&ab_channel=Rescue%3ATheBehaviorChangeAgency

Come for the Music, Stay to Quit Smoking

Megan Younce, 32, attended Commune Wednesday events in San Diego when she was in her mid-20s.“I had probably heard of it because of the bands and the local art," she says. "One month it would be a girl who made jewelry, one month a painter, one month these girls who buy vintage clothing and alter them. Always a local person.”

While Younce came for the cultural events of Commune Wednesdays, she stayed for a smoking cessation program that was eventually introduced. She's now been off cigarettes almost five years.

Was she aware that the campaign had specifically designated her a hipster?

"I definitely heard it from other people," she said. "That doesn’t surprise me, considering where the events were held."

Measuring Results

As it turns out, it’s “really hard in this population to find the same hipster year after year,” Ling says. So in order to measure their campaign's efficacy, the researchers had to use time-location sampling, often employed with hard-to-reach populations. While they weren't able to track the exact people who initially signed up for the study, they went to the same bars where the Commune events had been held, to survey whoever was present in the right age range.In San Diego, using this method, the researchers found a decrease in the hipster smoking rate over three years, from 57 to 48 percent, and a daily smoking decrease from 22 to 15 percent. There was no decrease in the rate for non-hipster peer groups who were not part of the Commune project.

Two other studies, in Albuquerque and Las Vegas, also found a smoking decrease in the Partier and LGBT groups after similar campaigns were run. A third study, in Oklahoma City, did not find a smoking decrease in the overall Partier population, but did find that the rate of daily smoking decreased for those who were aware of the brand called HAVOC. The rate actually increased for those who were not aware of it.

The researchers acknowledge the limitations of these small studies, but feel that the evidence for the effectiveness of this approach is mounting.

"We are cautious not to be overly confident about changes in tobacco use being attributable to our intervention," says Jordan. "What gives us more confidence is the repetition of these findings."

Laura Gibson, research director for the Tobacco Center of Regulatory Science at the University of Pennsylvania's Annenberg School for Communication, has studied anti-smoking communications for youth and young adults. She says other research corroborates that tailoring a message for distinct groups makes the target audience more likely to pay attention.

"Further, segmentation can help campaign planners put their message in places where those groups are more likely to come across them," she wrote in an email.

However, she said, creating separate anti-tobacco communications strategies for different groups could actually cost more money than creating a one-size-fits-all message, given that individual sub-cultures like hipsters aren't the only young adult groups with a smoking problem.

"If only hipsters are smoking, then perhaps there's no need for universal appeal, but that's not the situation," she said.

The data from San Francisco Commune intervention is being analyzed now, and Ling says she hopes to present it at the National Conference on Tobacco or Health in March.

Meanwhile, hipsters shouldn't feel singled out in having been stamped with empirically proven traits. For instance, among the characteristics of Partiers, says Jordan, are prioritizing fashion and a tendency to be "more concerned about their appearance."