Bay Area scientists have developed a new method to test drugs that are likely to be dangerous for pregnant women and cause heart defects in the fetus.

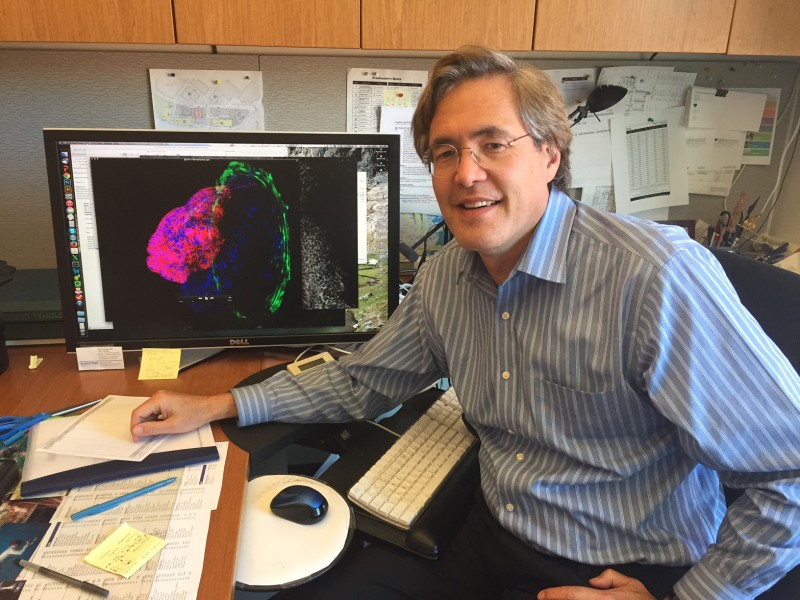

Researchers from UC Berkeley and the Gladstone Institutes, an affiliate of the University of California, San Francisco, grew beating heart tissue from stem cells -- essentially a mini human heart chamber in a dish. Stem cells have the potential to become any type of cell in the human body.

The researchers intend to use the system to screen medications intended for pregnant women to detect whether they will likely do any harm to the fetus. Among the most commonly-reported birth defects involve the heart.

Birth defects affect three percent of babies born in the United States every year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Birth defects are one of the most common causes of infant deaths.

[Watch the video below for a demo.]

In 2014, scientists in the UK developed a similar model to convert skin cells into beating heart cells in a petri dish. Previously, doctors would have needed to surgically remove heart tissue from patients to test new treatments, which is invasive and not practical.